One Belt, One Road (OBOR)

The two initiatives, ‘One Belt, One Road (OBOR)’ and ASEAN Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), are largely welcomed by ASEAN. ASEAN is in need of mega-regional initiatives to move forward as the Chinese economy slows down and restructures[1]. As Dollar[2] further argues, these different efforts are in fact complementary. He further adds that the kind of infrastructure financed by the Chinese initiatives, considered as the “hardware” of trade and investment, is necessary to deepen integration.

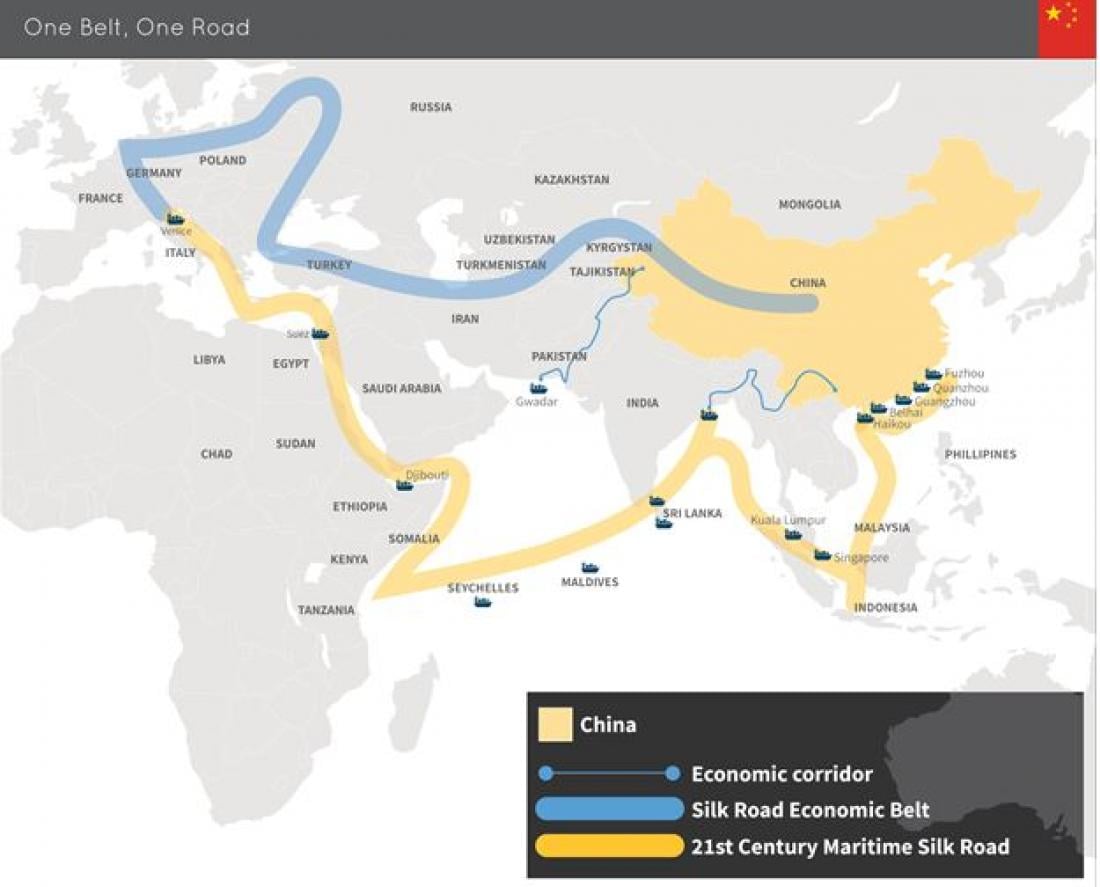

The OBOR promises to connect more than 65 emerging market countries and developing countries and a population of over four billion, a total worth of about US$21 trillion. It includes two main components, the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The former focuses on connecting China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia, the Persian Gulf through Central Asia and South East Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The latter complements the former by focusing on utilizing sea routes and Chinese coastal ports to link China with Europe via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, and the South Pacific Ocean through the South China Sea.

The OBOR, an ambitious idea in terms of scale and scope, is aimed at promoting economic cooperation amongst countries along the ‘belt’ and ‘road’ routes. What is critical here is that a vast amount of world trade already traverses these routes. As such, the OBOR thrust can be viewed from the following angles based on the China trade relations with ASEAN. From the Chinese side, it is one way for the country to redirect its domestic overcapacity (such as steel, cement and aluminum) and capital by banking on ASEAN’s (and Asia’s) infrastructure needs, apart from other geopolitical reasons[3] such as energy security.

For ASEAN, the underlying story of connectivity that characterizes this initiative is an opportunity to expand their goods and services and tap new markets. For example, Singapore, the regional trading hub, sees OBOR as an opportunity for their businesses to operate out of Singapore, and to also play a more significant role as a hub for foreign businesses to tap neighboring markets [1, 4]. Reflecting the importance Singapore holds for OBOR, the Singapore Business Federation (SBF) together with Lianhe Zaobao (the Chinese flagship newspaper of Singapore Press Holdings) jointly developed a portal for OBOR, which was launched on 8 March 2016. It is Southeast Asia’s first comprehensive website focusing on OBOR, with the objective of driving a deep understanding of OBOR among Singapore enterprises, as well as offering Chinese readers around the world a Singaporean and Southeast Asian perspective on OBOR[5].

Similarly, Malaysia looks forward to opportunities for regional financial players to participate in project financing[1]. Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has already signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) on the RMB clearing arrangements in 2015. In the MoU, both central banks agreed to coordinate and cooperate on the supervision and oversight of the RMB business, exchange of information, and to facilitate the continuous improvement and development of the arrangement.

Newer member economies such as Vietnam see rising opportunities in engineering insurance and other lines of business such as maritime, and therefore is already revising its insurance and related regulations to capitalize on the growth prospects in this sector[6]. Based on the Economist Corporate Network (ECN) analysis, Indonesia stands to be the biggest beneficiary among the ASEAN economies, with approximately US$87.4 billion identified in OBOR related pipeline infrastructure projects[1]. More importantly, this initiative will open possibilities for removing trade and investment barriers[4], which has seen rather slow progress within the ASEAN region.

According to Liu[7], based on a survey, more than 70 per cent believe that ASEAN would benefit from this initiative. Mooney[8] forwards that Southeast Asia is already emerging as a major beneficiary of OBOR, with Chinese companies accounting for 17 per cent of infrastructure investment across the region. Major port projects in Southeast Asia that have had Chinese investment include the expansion of Kuantan Port and phase 1 development of Samalaju Port, both in Malaysia, and the development of Tanjung Sauh Port on Batam Island in Indonesia. The ECN survey[1] of business leaders’ perceptions on the OBOR initiative also indicate that around 60 per cent of their respondents expect this initiative to further contribute to the ASEAN integration process, and to boost intraregional trade and investment. From the Chinese perspective, since OBOR is a long-term initiative that will be implemented bilaterally between China and her different partners, it is still premature to identify which partnerships would provide China better prospects to vent some of its surplus.

In the case of the AIIB, a comparatively smaller initiative than the OBOR, is an important strategy to support the implementation of the latter as huge capital injection is needed for the OBOR[4]. It has indeed garnered much interests and overwhelming support from ASEAN (and outside the region), as the region, more specifically, looks forward to a new multilateral development bank (MDB) that is more relevant to their needs, and more efficient than the existing ones, which are generally slow in project preparations. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank have strict requirements and conditions for giving funding for infrastructure projects, which may not suit the developing countries’ conditions[4]. This is reaffirmed by the participation of all ASEAN members in the AIIB[9]. As Das[9] explains, Southeast Asian states, compared to their Northeast Asian counterparts, are generally more in need of the developmental assistance associated with China’s initiatives. This is confirmed by open declarations of some ASEAN states. At the opening of the Afro-Asia Summit in Jakarta on April 22, 2015, Indonesian President Joko Widodo gave a strong endorsement to the AIIB: “those who still insisted that the global economic problems could only be solved through the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank, were clinging to obsolete ideas”[10]. Thailand’s Vice Minister for Finance, Kiatchai Sophastienphong, has also publicly declared his support for the AIIB[7]. The AIIB, which targets infrastructure development, serves the needs of ASEAN. As China has a much larger say through the AIIB, given its weight in this outfit relative to the other multilateral lending institutions, this could have far reaching implications for the future of ASEAN-China relations[10, 11].

Clearly both the OBOR and AIIB, taken together, are initiatives that will deepen the inter-links between China and ASEAN that have already been established through trade and investment. Having said that, the Southeast Asian countries have expressed some reservations on the OBOR, while other concerns may also follow from this initiative. The following illustrates some of these points:

• One concern is that China may “use economic incentives to lead ASEAN into broader and deeper ‘all-dimensional’ cooperation,” and thereby threaten the regional body’s unity. Their fear is that “in the long run, when China’s growing economic power morphs along more strategic-oriented pathways, pressure will mount on ASEAN members to reciprocate China’s regional and global interests”[12].

• Another issue is on the initiative in itself, which reorders Asia in ways that make ASEAN and its concerns less central[9]. Das also forwards that the bilateralism that has typified China’s approach lends to China’s structural advantage to set the terms. This is further supported by the findings from the ECN survey; approximately 80 per cent of the respondents expect OBOR’s greatest impact to lie in the extension of Chinese influence throughout the region. The risk of overdependence on China could be potentially unsettling for some member States[1].

• A related issue on the connectivity story of OBOR is how it aligns with the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC). The MPAC, launched in 2010, is ASEAN's flagship infrastructure project aimed at enhancing land connectivity and integration among ASEAN member countries. Some opine that the former will complement the latter[13], while others feel that ASEAN must ensure that the MPAC retains its centrality in the connectivity projects in ASEAN that may come under the OBOR[14].

In response to some of those concerns, China has tried to make a convincing argument that the OBOR initiative synergizes with ASEAN’s development strategies and could play a complementary role in the building of the ASEAN community[1, 15]. Notwithstanding that, some of these concerns could, however, potentially interfere with the Chinese plans, unless the trust deficit is addressed and OBOR is somehow projected as a regional initiative rather than a Chinese initiative[16]. More so when the maritime “road” sails through the contested waters of the South China Sea. Understandably, as these initiatives roll-out, they will be met with both support and suspicion in ASEAN.

Contact information:

(1) Associate Prof. Dr. Evelyn Shyamala A/p Paul Devadason

Department of Economics

Faculty of Economics and Administration

University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

email: [email protected]

(2) Associate Prof. Dr. Vgr Chandran A/l Govindaraju

Department of Development Studies

Faculty of Economics and Administration

University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

email: [email protected]