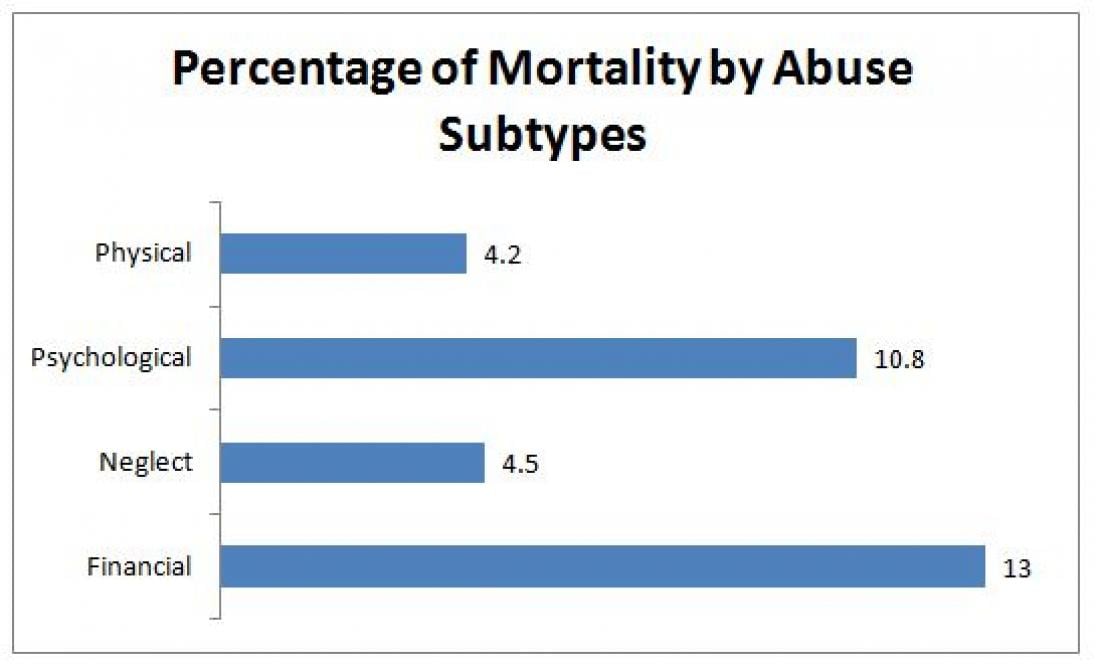

Percentage of mortality among older adults in Kuala Pilah according to subtypes of EAN *sexual abuse was excluded because the number of cases was too small

Like other developing countries, the older population in Malaysia is rapidly growing in comparison to the younger age groups. In 1991, it was estimated that there were 1 million older adults, representing 5.8% of total population. Within two decades, this figure more than doubled; 2.2 million older adults comprising 7.7% of total population. By 2040, it is predicted that 17.6% (seven million) Malaysians will be those aged 60 and over. Furthermore, the oldest-old group (80 and over) is projected to quadruple between the years 2010 to 2050. This demographic transition, along with the on-going urbanization and changes in social structures are likely to increase the vulnerability of the older population to marginalization, abuse and exploitation if preparations and resources in the country remain inadequate.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined Elder Abuse and Neglect (EAN) as “a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person”. The notion of ‘relationship of trust’ plays a central role here and thus clarifies the nature of this dilemma. Those entrusted generally refer to family members, close friends, neighbours, caregivers and any person on whom the older person depends, to safeguard his well-being. The five common subtypes of EAN are physical abuse, psychological abuse, financial abuse, sexual abuse and neglect.

It has been reported that the worldwide prevalence of overall EAN is 15.7%, with psychological abuse being the most common type. In Malaysia, the Prevent Elder Abuse and negleCt initiativE (PEACE), found that 4.5% older adults in the rural area reported having been mistreated in the last 12 months, whereas the lifetime prevalence was 8.1%. On the other hand, 9.6% urban poor elders reported having experienced abuse in the past 12-months in another study. Contrary to the global finding which showed that psychological abuse was most common, financial abuse was the leading subtype in rural Malaysia.

In the United States and Australia, EAN has been shown to be fatal. Older adults who were abused, regardless of the subtype, died earlier than those who were not abused. A similar study in rural Malaysia demonstrated a possible link between mistreatment or exploitation in late life and death. Malaysian elders who admitted to having experienced abuse ever since they turned 60, died in greater percentages when compared to those who were never abused, upon a short follow-up of two years. Proportions of death were highest in financial abuse, followed by psychological abuse and neglect.

Figure 1 illustrates the findings of a study conducted in Kuala Pilah which tracked mortality among a cohort of older adults after two years. How abuse causes death is still unclear, but a number of possible explanations can be offered. Chronic stressor – in this case EAN – has been shown to adversely affect physiological processes in the body which may eventually manifest as clinical symptoms, health complaints and different illnesses. Numerous studies have established the connection between EAN and a wide range of health problems such as digestive symptoms, bodily pain, metabolic syndrome, headache, suicidal ideation, and depression, sleeping problems, incontinence and many more. To a certain extent, abuse is therefore responsible for the deterioration of physical and mental well-being of victims, which gradually contribute to higher risks of death.

While severe forms of physical abuse can directly lead to injuries and fatalities, the link between other subtypes such as financial and psychological abuse and death is more subtle. In the case of repeated and prolonged financial exploitations, victims do not only suffer from financial losses but also mental distress as a result of the broken trust by their loved ones. In addition, financial deprivation limits older adults’ mobility, access to health care and purchasing power. These can easily result in social isolation, deterioration of living condition, and worsening of existing illnesses, with an eventual outcome of death.

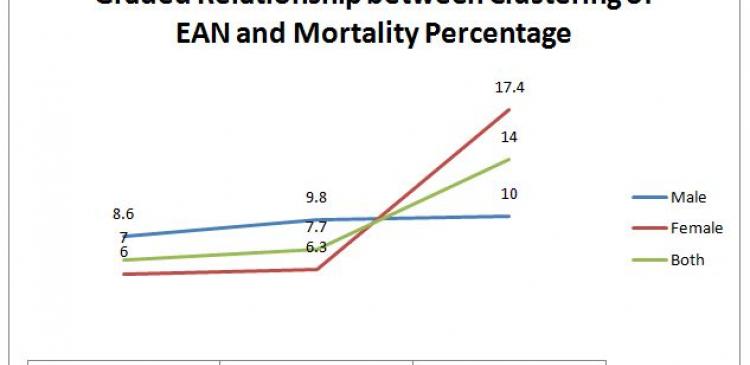

Clustering of abuse, defined as experiencing more than one subtype of EAN, was found to correspond positively with percentages of mortality. This means older adults who are abused in different forms (more than one type) show higher percentages of death compared to those abused in a single dimension. Findings from PEACE also revealed a striking difference in mortality patterns and percentages between abused males and females. Female victims seem to be more vulnerable – their percentage of death almost tripled from abuse of a single type to abuse of two or more types, while the percentage of male deaths increased only by 0.2%. Figure 2 demonstrates the dose-response relationship between EAN clustering and death percentages, along with gender differences in mortality.

Based on the study results, it can be postulated that there is a link between abuse in late life and risks of mortality, even though it is still difficult to ascertain whether EAN causes death in the Malaysian context. Nevertheless, evidence from other countries has corroborated this relationship. What we need in the future are more rigorous investigations into how different subtypes of EAN affect mortality rates and how gender influences the relationship between abuse and death. This will assist policy-makers in formulating more efficient intervention programs, and healthcare providers in tailoring clinical approaches accordingly. Given that financial abuse is the most common type of EAN in Malaysia, more studies are also required to further understand this phenomenon in order to enable the designation of effective and holistic preventive measures.

Contact:

1. Dr Raudah Mohd Yunus

Julius Centre University of Malaya

Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Email: [email protected]

2. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Noran Naqiah Hairi

Julius Centre University of Malaya

Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Email: [email protected]

3. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Choo Wan Yuen

Julius Centre University of Malaya

Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Email: [email protected]