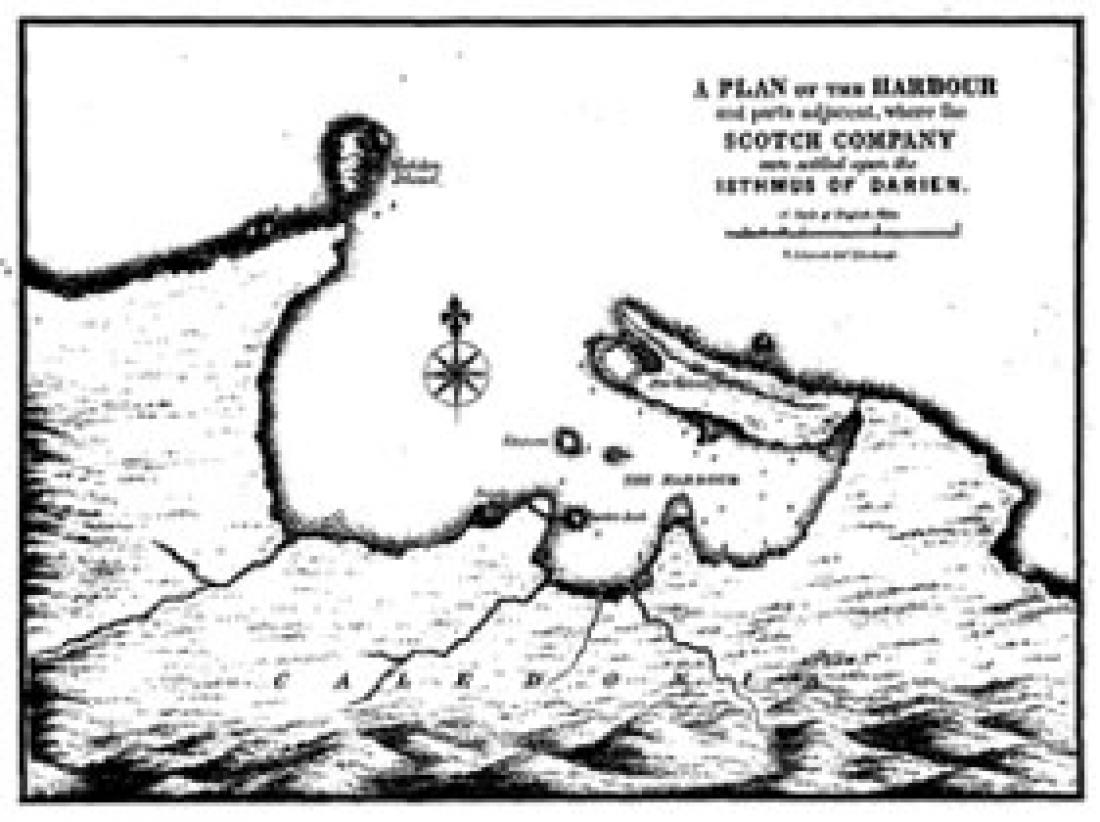

Map of Darien in the late 17th century

Referendum on Scottish Independence

September 18, 2014, will be a fateful day for the United Kingdom, and particularly for Scotland. A national referendum will be held on whether to abandon the Treaty of the Union, concluded and brought into effect by the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland in 1707, and to dissolve the Kingdom of Great Britain that was formed as a result of the Treaty. Voters will be asked to answer simply “yes” or “no” to the question of whether to annul the union; a majority of valid “yes” votes would mean the end of the Kingdom of Great Britain, and Scotland would become a sovereign independent nation for the first time in three centuries. Originally, the anti-independence campaign (those who want to remain within the UK) was expected to win comfortably, but opinion polls conducted just before voting day have shown the two sides evenly matched. Rather than venture to predict the result of the referendum, however, I want to talk here about the historical background of the situation and the relationship to modern ethnic issues. As for the impact that a decision for independence would have on the politics and societies of the UK and Europe, I intend to discuss this separately later.

Historical background

Three centuries may sound like a long time, but within the course of British history, it is not really all that long. Firstly, there are big ethnic differences between the two nations. The English people have been gradually shaped by repeated invasions of Anglo-Saxons, Normans, and others. However the Scots have maintained a relatively high degree of ethnic purity, and there is an extremely strong sense of solidarity, nationalism, and community spirit, especially among the Highlanders in the north. History often shows that it is normal, if anything, for neighboring nations to get along badly. A provisional border with England was drawn by King Malcolm II of Scotland at the end of a series of wars in 1018, although countless battles took place between the two countries even after this date. Even in more recent times, things had not changed. England was displeased by the way Scotland would arbitrarily extend its territory without consultation. In the late 17th century, for example, Scotland planned to establish a colony it called Darien, in what is now part of Panama. The English blatantly obstructed these plans and the Scots suffered thousands of fatalities along with economic losses that brought their nation close to bankruptcy. Seeing their predicament, England offered assistance to Scotland in the name of a union. The union was actually nothing more than a bail-out merger on a national scale. The saying, “The Union Bought for English Gold” expressed the situation very well. It is no wonder, perhaps, that many Scots cast a frosty eye on the union that came about in such a way. Two large rebellions against the government in London were organized, mainly by Highlanders and under the name of the Jacobites, in 1715 and in 1745-1746, both of which were subsequently crushed.

Scotland’s present and future

In the latter half of the 19th century, Scotland underwent such remarkable industrial development that its shipbuilding (battleships such as the Japanese Asahi, which played a key role in the Battle of Tsushima, were built there), machine industry, and so on were considered superior to those of England. Of course Ireland’s independence movement from the late 19th century also had an influence on Scotland. During the two World Wars, however, the unifying force keeping the Scots within the British Empire exceeded the impetus toward independence. Since the end of World War II, the desire for Scottish self-government and independence has intensified, resulting already in 1998 in the establishment of an autonomous parliament and the launch of an autonomous government.

The success of North Sea oil from the 1970s and the expansion and development of the EC and European Union are two key factors that have inspired confidence within Scotland to be able to maintain and develop its own economy without relying on England. In particular, the success of crude oil extraction reinforced the idea of resource nationalism, namely that this important resource was the property of the Scots rather than all of Britain, and the vast European Community and later the European Union seemed to offer a much larger market than Britain’s national economy. But Scotland’s present call for independence cannot be explained just by the existence of North Sea oil and the EU. All UK governments since the Thatcher administration have reduced government support of welfare and education and increased the burdens on individuals. In contrast, Scotland’s autonomous government has tried to maintain the nation’s traditional spirit of mutual assistance.

The autonomous government has maintained a system of free prescriptions under the National Health Service and in principle exempted Scottish-domiciled students from undergraduate tuition fees at Scottish universities. To this extent, Scotland has already taken a clearly different course from the neoliberalism adopted by the UK since the Thatcher years, and is likely to strengthen this policy if it achieves independence. Even if independence is rejected, the autonomous government will, within its powers, maintain policies that distinctly differ from those of the central government in Westminster. Whatever the outcome, there is no doubt that this referendum will become an important milestone for Scottish nationalism.

*This article was originally published in Japanese on September 16, before the referendum

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shin Matsuzono

Professor, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Waseda University

Professor Matsuzono specializes in Western History in the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Waseda University. He is a Fellow of the UK Royal Historical Society (FRHistS). Born in 1960, he graduated from the Waseda University School of Political Science and Economics in 1983, and earned a master’s degree from its Graduate School of Political Science in 1986. In the UK, he earned a PhD from the University of Leeds in 1990 and served as a fellow at the University of Edinburgh from 2002 to 2003, and at Wolfson College, University of Oxford, from 2012 to 2013. His main publications include The Making of the UK Parliamentary Politics: Focusing on ‘The First Political Party Era’ (1994) [Igirisu Gikai Seiji no Keisei—‘Saisho no Seito Jidai’ o Chushin ni] and Parliamentary Politics and the Development of the Industrial Society: A History of 18th Century Britain (1999) [Sangyo Shakai no Hatten to Gikai Seiji: 18 Seiki Igirisushi] (both Waseda University Press).