By Feng Zengkun

SMU Office of Research – When the word “property” comes to mind, most people will relate it to land and real estate, which for the most part have clear laws related to their use and sale. The rights of people who deal in assets such as digital currency bitcoins, carbon credits and even virtual assets in massively multiplayer online games, however, are often much less well-defined.

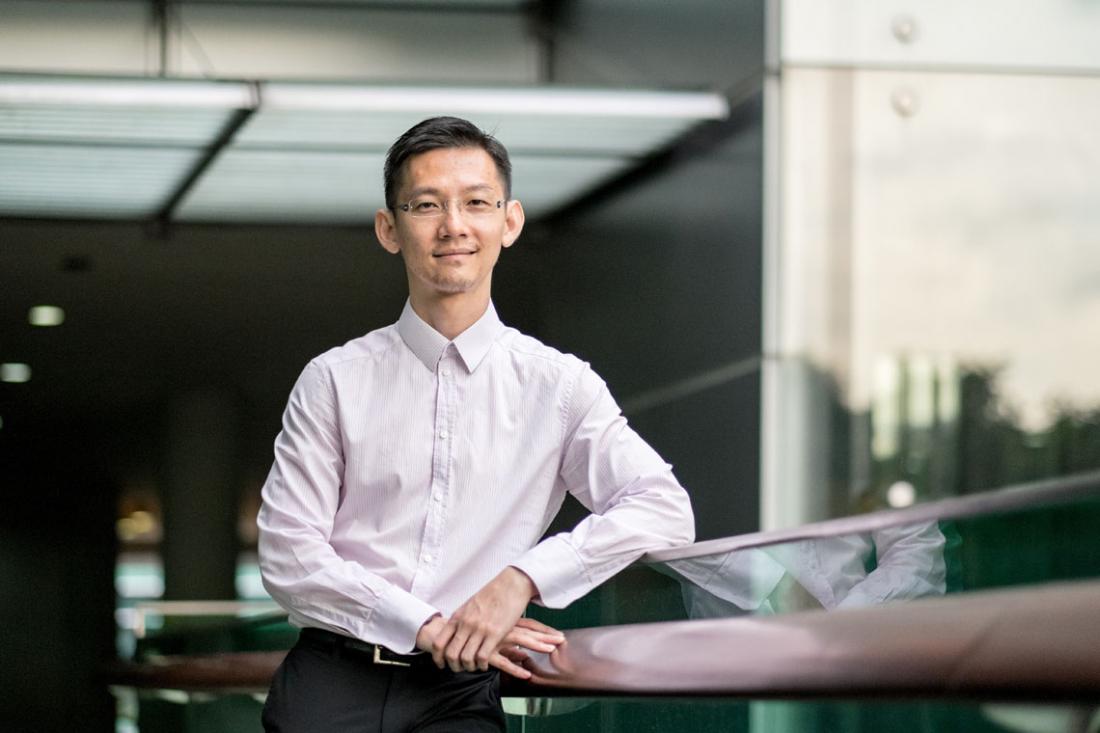

The research of Kelvin Low, Associate Professor at the Singapore Management University (SMU) School of Law, focuses on trust law and the law of property, specifically on how the law protects people’s property. He recently won an Honourable Mention in the Journal of Environmental Law’s 2015 Richard Macrory Prize competition, for a research paper that examined how legal ambiguities in the European Union (EU) carbon credit trading system are detrimental to its purpose.

Carbon credits as EU likes them: A bad precedent

Professor Low’s paper, titled “Carbon Credits as EU Like It: Property, Immunity, TragiCO2medy?”, was co-written with Associate Professor Jolene Lin of the University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law. In it, they explained that the EU had decided not to define the legal nature of its carbon credit, which allows the owner to emit one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent during a specified period. Instead, the EU allowed each member state in the trading system to create its own definition.

This decision left participants of the scheme in a state of legal limbo as it was difficult to predict how their rights would be protected in any particular member state, particularly because the designers of the scheme failed to distinguish between a right and a register of the same. It also sowed confusion for the credits’ owners as the credits are meant to be traded across borders, and yet would change in nature upon crossing a border.

In the paper, Professor Low analysed how this paucity of guidance had worsened the misfortunes of both parties in the Armstrong DLW GmbH v Winnington Networks Ltd lawsuit in England in 2011. Winnington, a trader of carbon credits registered with the United Kingdom registry, had bought 21,000 credits from Zen Holdings, a Dubai-based firm. Winnington, however, was unaware at the time that the credits had been “stolen” from German company Armstrong.

While the trial judge determined that the carbon credit constituted a property right of some sort, he struggled to determine what private-law rights were conferred by this sort of property. Professor Low found that concessions made by both parties during the trial, certain possibly mistaken assumptions and a number of unexplored claims suggest that the judge’s decision in favour of Armstrong is unlikely to be the final word on the subject. He believes that similar lawsuits will become more common in future as intangible property, often poorly defined as a matter of law, increasingly represents a larger proportion of global wealth.

From credits to currency

Professor Low believes that intangible property such as carbon credits and digital currency bitcoins are remarkably poorly-understood from the perspective of property law because the law has no stable definition of “property” and some property lawyers reject intangible property as property altogether.

With tangible property such as a car, the legal rights to the asset and the asset itself are two distinct things. With intangible property such as carbon credits, on the other hand, the legal rights are the property itself, since there is no physical product. As such, most intangible property, such as intellectual property, do not cross national borders. Failure to understand this distinction could lead to odd situations, as in the case of the EU carbon credits, where the carbon credits change upon crossing borders depending on domestic laws.

“The way in which my rights to my car are protected may change when I drive across the Causeway to the extent that Malaysian law differs from Singapore law, but the car remains physically the same. It does not transform. However, intangible property is whatever the particular legal system chooses to protect,” he explains.

Professor Low plans to work with colleagues from the SMU Sim Kee Boon Institute for Financial Economics to study whether digital currency bitcoins, another intangible product, can and will be treated as property in the law and if so, how rights to bitcoins should be protected. He notes that the common law generally classifies property in two ways: tangible things that are owned through physical possession of them, and intangible things that are owned through the legal rights to them.

“Bitcoins are clearly not the former since they cannot be possessed, but until courts or the legislature recognise ‘owners’ as having any legal rights to them, they are not obviously the latter either. So bitcoins are extremely interesting from the perspective of a property lawyer because they represent something quite unique,” he says.

He adds that bitcoin owners’ rights will only be clarified when there is a dispute before the courts. If bitcoin owners are granted property rights over their digital money, this will also be a remarkably rare occurrence in modern times of new property being recognised by the courts rather than by the legislature.

Holistic view on property needed

After his bitcoin project, Professor Low intends to start work on a textbook on the law of property. He says that while Singapore has textbooks on land law and personal property law, there is no overarching text on the holistic law of property. This will become increasingly important as many interesting new questions are being raised even in the field of tangible property.

He says, “Most of our law of tangible property is concerned with protecting possession and preventing physical interferences, but with our property becoming increasingly ‘smart’, it will increasingly become possible to interfere with them without actual direct physical contact.”

“Once upon a time, I probably shared the view that intangible property is not really property, but the more I explored the periphery of the law of property, the more I came to believe that this view is, while not without its merits, entirely too simplistic.”