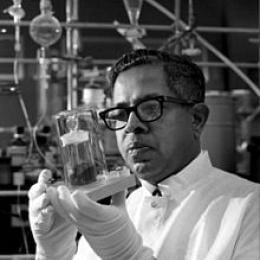

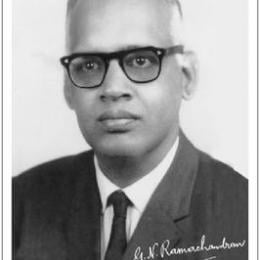

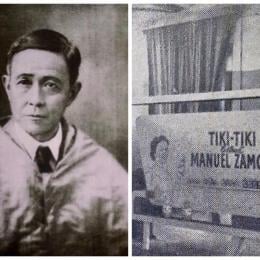

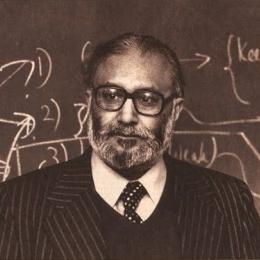

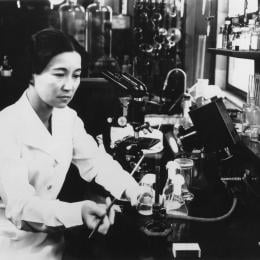

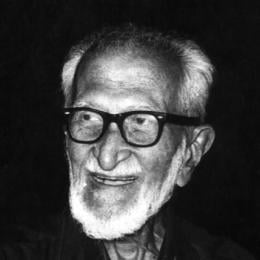

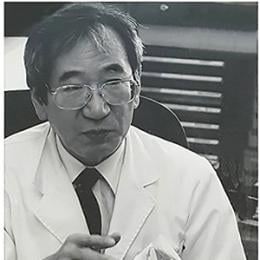

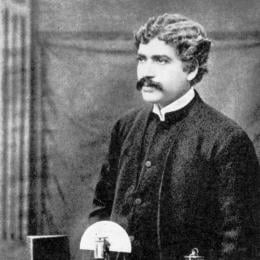

Today's research stands on the shoulders of those who came before us. Get to know these fascinating researchers. Because role models matter.

While assisting my nieces on Asian pioneers in science, I came upon your Giants in History. Thank you, love the site, really helps to inspire young people to enter the science fields.

Dal Basi