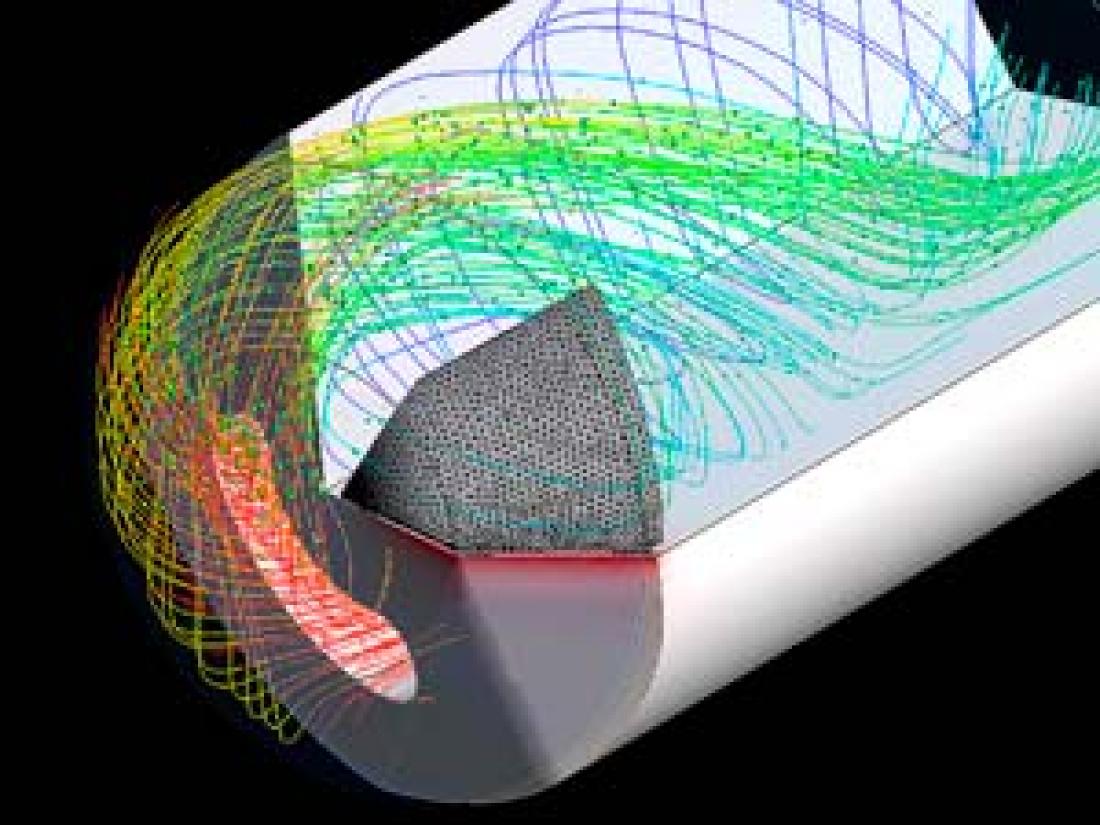

High-pressure coolant application in deep hole gun drilling.

© 2017 A*STAR Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology

By simulating the removal of chips during the drilling of deep holes in metals and metal alloys, Singapore's Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) researchers have paved the way for gun drills that are more durable, reliable, and have longer lifespans [1].

Gun drilling is a process for producing deep holes — with depth-to-diameter ratios greater than 10:1 — in metals and alloys, and is used across a number of industries, from the manufacture of firearms and combustion engine parts, such as crankcases and cylinder heads, to medical tools and woodwind musical instruments. Small fragments or chips produced during drilling affect the wear and tear on gun drills.

Gun drills have a unique head geometry that uses high-pressure coolant, supplied through internal conduits running from the drill bit to the bottom of the hole, to remove chips as the drill advances. Tnay Guan Leong and colleagues from the A*STAR Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology and Institute of High Performance Computing were able to simulate the effects of different drill head geometries on chip removal to develop a novel computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model to optimize drill design.

“Removing chips from holes with small diameters and high length-to-diameter ratios, often greater than 250:1, is particularly difficult,” says Tnay. “If the chips start to clog inside the hole, they can increase drilling torque, leading to the drill breaking inside the hole.”

Observing the behavior of chips is challenging, however as the process takes place in a closed zone. To address this, the researchers developed a CFD model to simulate the motion of the chips as they are transported in the high-pressure coolant. They verified their simulations with experimentation.

By varying the shoulder dub-off angle of the drill’s head the research team simulated the transportation of the chips under different geometries, allowing them to identify the optimal drill design for chip removal.

“The shoulder dub-off angle is key to the control of the coolant flow rate and flow direction to the cutting zone,” explains Tnay. “Our modeling showed that, when the dub-off angle increases chips travel towards the bottom of the hole, increasing the risk of clogging.”

Current gun drill designs use a fixed shoulder dub-off angle of 20 degrees, but they found that drill performance greatly improved as the angle approaches zero.

“Our next step will be to evaluate a gun drill with zero degrees dub-off angle, and use our model to study the effects of changes in the cutting edge geometries, coolant pressure and coolant properties,” says Tnay.

The A*STAR-affiliated researchers contributing to this research are from the Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology and the Institute of High Performance Computing. For more information, please visit the Precision Engineering Center of Innovation webpage.