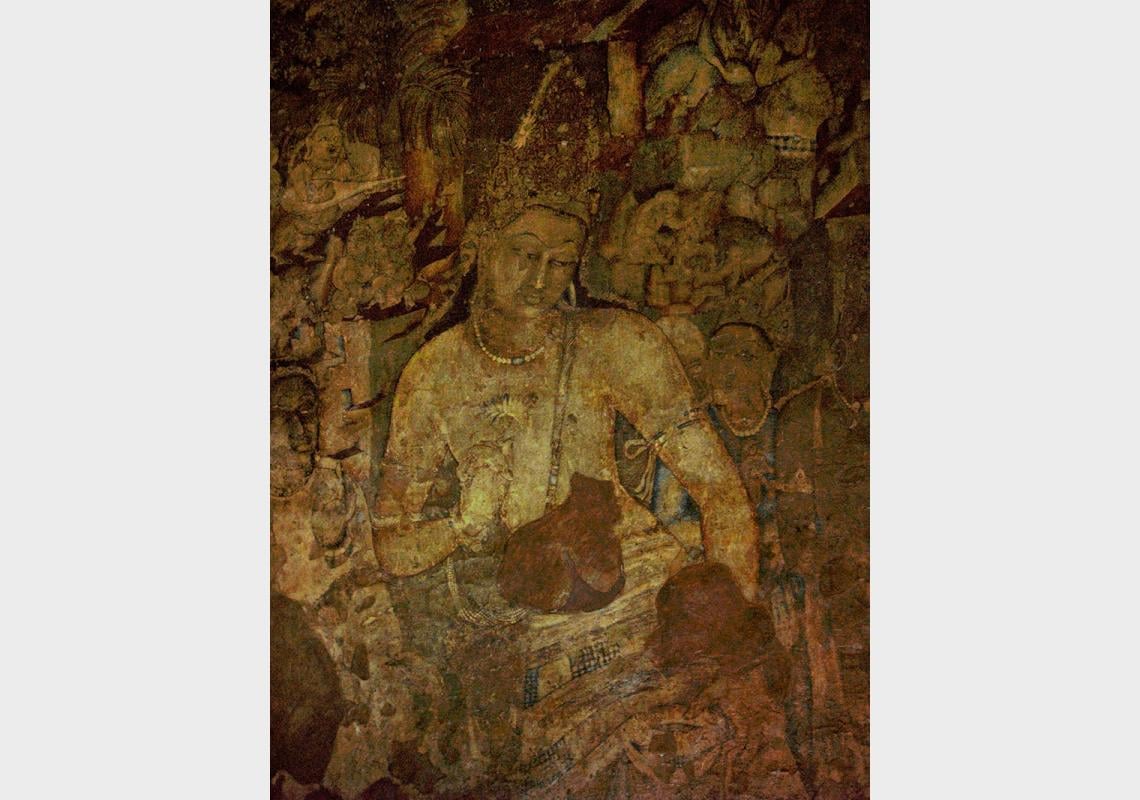

Bodhisattva Padmapani in Ajanta Caves.

Among the earliest and most significant examples of cave painting in India, the Ajanta murals were executed on the inner walls and ceilings of the Ajanta caves in present-day Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Their main subject is the Jatakas, which narrate stories of the Buddha through his lives as various bodhisattvas. The caves and the murals inside them were created in two distinct periods. The first period spans the second and first centuries BCE, attributed the patronage of the Satavahana Dynasty; the second was during the late fifth CE, possibly during the reign of the Vakataka king Harisena.

In both periods, a marked difference has been observed between the murals on the ceilings and those on the walls. The former depict floral patterns, geometrical shapes, animals and birds. Religious motifs are notably absent. The effective use of shading and highlighting adds a three-dimensional effect to the paintings.

Wall murals, in contrast, focus on more overtly religious iconography. Wall murals of the first period are difficult to discern since they have been heavily damaged over time. They appear to depict important Buddhist symbols such as the Bodhi tree. Murals from the second period depict iconic scenes from the Jatakas, including Asita’s visit to the infant Buddha, the temptation of Buddha by Mara and his forces, miracles performed by the Buddha, tales from the Jatakas of kings such as Sibi, lndra and Sachi, court scenes, legends of Nagas and various scenes of battle and hunting. However, the exact events and figures represented is a matter of considerable debate. These murals are believed to be the result of patronage by prominent individuals who followed Mahayana Buddhism; some of the figures painted alongside the Buddha might be members of their families. Murals from this later stage are considered to have played an important role in teaching, owing to their pictorial representation of the concept of impermanence – a central theme in Buddhism.

The murals from the first phase use a limited range of colours, mostly confined to different shades of ochre, whereas those from the second phase use a rich mosaic of colours consisting of yellow, red, white, black and green. The pigments are believed to have been sourced locally from residual minerals of volcanic rocks. However, the occasional use of lapis lazuli for blue suggests that at least some pigments may have been imported from the Iranian plateau. The layer of paint in the murals measures 0.1 millimetre in thickness, with the underlying layer of fine plaster varying from cave to cave but generally ranging between 2 and 3 millimetres.

While there is considerable dispute about whether the murals were made using tempera or fresco secco, there is general agreement on the fact that they are not fresco buono, where the painting is done on wet plaster. It is widely accepted that a mud plaster – made by combining water, rock-grit or sand and organic matter such as vegetable fibres, paddy husk, grass and other organic fibrous material – was first applied to the compact volcanic basalt walls of the caves to form the foundation of the paintings.

The murals are believed to have been made mostly by families that functioned as individual guilds engaged in painting. It is possible that, in some cases, the monks who resided in the monastery of the Ajanta caves supervised the production of the murals.

The visual style of the murals is highly sophisticated. Outlines are bold and elegant; compositions are full of activity and detail; and human figures are stylised, often ornately decorated with clothing or jewellery, sensitively shaded and provided with emotive facial expressions. The Ajanta artists’ style of depicting elongated eyes and dynamic hand gestures is considered to be highly influential in the history of world art: it has been linked to mural paintings in Central Asia and manuscript paintings in China and Japan.

Ajanta Cave 1 Mahajanaka Jataka Mural 2, Jean Pierre Dalbéra, c. 2015,

The Ajanta murals frequently depict scenes from daily life. Women are usually portrayed in traditional roles, such as those of a mother or wife. They are are depicted with shapely bodies, generally in the tribhanga posture, wherein the body is composed around three main axes. In contrast, men are generally portrayed as saintly or ascetic.

Historians believe that the caves were in use until at least the eighth century CE, after which they were abandoned. They were rediscovered in 1819, overgrown with vegetation and filled with debris, by a British officer named John Smith, during a tiger-hunt in the region. The preservation of the murals has been an ongoing challenge ever since this rediscovery. Both environmental and human agents have been responsible for their deterioration, including wide fluctuations in temperature and humidity, atmospheric pollution and vandalism. Older techniques of preservation used in the colonial period, such as the use of unbleached shellac and Victorian varnish, caused considerable damage to the murals. The Archaeological Survey of India undertook an advanced chemical cleaning and preservation and restoration of the murals in 1999. These efforts removed the layers of dirt, grime and shellac and secured the crumbling edges of broken plaster by filleting, so that the original compositions were not altered.

After their rediscovery, many British drafters, Indian artists and art students documented the murals by reproducing them as paintings. The Royal Asiatic Society in London commissioned some of the first of these painted reproductions in the 1840s, executed by the British painter Major Robert Gill; these were destroyed in a fire two decades later. The Sir JJ School of Art, under the leadership of the British artist John Griffiths, undertook further documentation in the 1870s. Students at the school reproduced the murals, and most were subsequently sent to the then-newly established Victoria and Albert Museum, London. It is in large part due to these reproductions that the Ajanta murals are known around the world today. The museum still possesses 166 of these paintings, which were last displayed in 1955 and have been in storage since. In the 1920, the Indian archaeologist Ghulam Yazdani, appointed by the Nizam of Hyderabad, became the first person to photograph the Ajanta murals.

The Ajanta caves were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983. As of writing, they continue to be a major tourist attraction.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and a Blog, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.