Despite rapid surface warming, the team found that global mean climate velocities in the deepest layers of the ocean (>1,000 m) have been 2 to nearly 4-fold faster than at surface over the second half of the 20th century.

Reporting in the journal Nature Climate Change, an international team of scientists, led by the University of Queensland in Australia and involving Hokkaido University, analyzed contemporary and future global patterns of the velocity of climate change across the depths of the ocean. Their metric describes the temporal rate and direction of temperature changes, as a proxy for potential shifts of marine biota in response to climate warming.

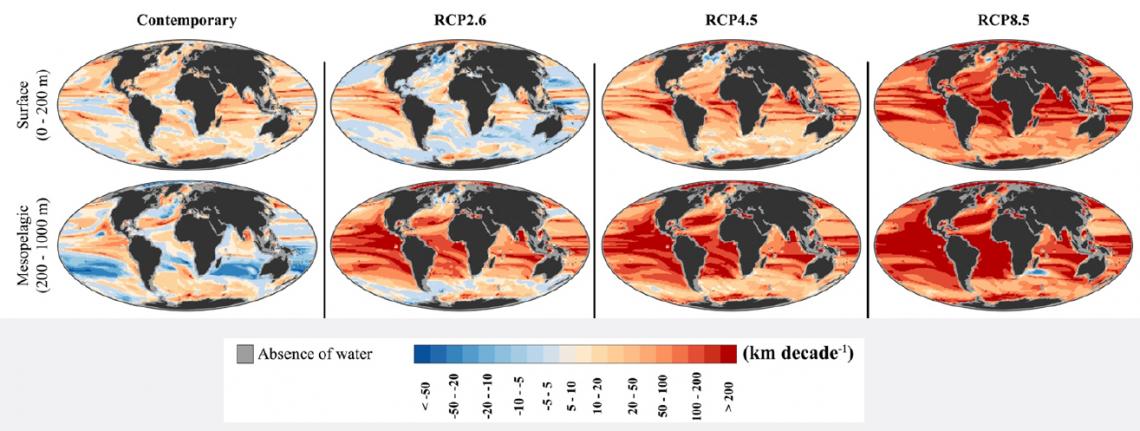

Despite rapid surface warming, the team found that global mean climate velocities in the deepest layers of the ocean (>1,000 m) have been 2 to nearly 4-fold faster than at surface over the second half of the 20th century. The authors point to the greater thermal homogeneity of the deep ocean environment as responsible for these larger velocities. Moreover, while climate velocities are projected to slow down under scenarios contemplating strong mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions (RCP2.6), they will continue to accelerate in the deep ocean.

Climate velocity (km decade-1) for contemporary (1955-2005) and projected future sea temperatures (2050-2100) at sea surface and the mesopelagic layer under three IPCC greenhouse gas emission scenarios (RCP2.6, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5).

“Our results suggest that deep sea biodiversity is likely to be at greater risk because they are adapted to much more stable thermal environments,” says Jorge García Molinos, a climate ecologist at Hokkaido University's Arctic Research Center, who contributed to the study. “The acceleration of climate velocity for the deep ocean is consistent through all tested greenhouse gas concentration scenarios. This provides strong motivation to consider the future impacts of ocean warming to deep ocean biodiversity, which remains worryingly understudied.”

Climate velocities in the mesopelagic layer of the ocean (200-1000 m) are projected to be between 4 to 11 times higher than current velocities at the surface by the end of this century. Marine life in the mesopelagic layer includes great abundance of small fish that are food for larger animals, including tuna and squid. This could present additional challenges for commercial fisheries if predators and their prey further down the water column do not follow similar range shifts.

The authors also compared resulting spatial patterns of contemporary climate velocity with those of marine biodiversity for over 20,000 marine species to show potential areas of risk, where high biodiversity and velocity overlap. They found that, while risk areas for surface and intermediate layers dominate in tropical and subtropical latitudes, those of the deepest layers are widespread across all latitudes except for polar regions.

The scientists caution that while uncertainty of the results increases with depth, life in the deep ocean is also limited by many factors other than temperature, such as pressure, light or oxygen concentrations. “Without knowing if and how well deep ocean species can adapt to these changes, we recommend to follow a precautionary approach that limits the negative effects from other human activities such as deep-sea mining and fishing, as well as planning for climate-smart networks of large Marine Protected Areas for the deeper ocean,” says García Molinos.

Jorge García Molinos at the Arctic Research Center of Hokkaido University

Contacts:

Assistant Professor Jorge García Molinos

Arctic Research Center

Hokkaido University

Email: jorgegmolinos[at]arc.hokudai.ac.jp

Naoki Namba (Media Officer)

Institute for International Collaboration

Hokkaido University

Tel: +81-11-706-2185

Email: en-press[at]general.hokudai.ac.jp