This story is featured in the Asia Research News 2023 magazine. If you would like to receive regular research news, join our growing community.

Get the news in your inbox

Recipient of the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Japanese government. Professor emeritus. Awards from academic organizations in the US, France and Italy, to name a few. It is safe to say that Ken’ichi Nomoto is regarded as one of the best experts in the world when it comes to finding out how stars evolve and how they end their lives in a dramatic explosion.

Nomoto, currently a visiting senior scientist at the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU), has had his name appear on more than 200 papers since joining the institute in 2008 as one of its first members when he was a principal investigator.

Ken’ichi Nomoto, one of the world's leading experts on the evolution of stars, is a visiting senior scientist at the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe.

While his academic career began long before the Kavli IPMU was established, Nomoto says today he is still researching the same thing he started studying when he was a university student in the 1970s, which is creating models for star evolution and supernovae, or star explosions.

“As a high school student I would go to talks by [radio astronomer] Takeo Hatanaka, and I read his book about star evolution.

“I was interested in physics, but I also liked history, so the word ‘evolution’ caught my attention. I combined stars and history. We’re at the point now where we have the technology, like the James Webb Space Telescope, to study those first stars in the universe and how they formed.”

Although Nomoto found his research area of expertise at a young age, he says he had never intended to become an international expert on the subject and had never even imagined going outside of Japan for his work. He says that the research grants academics relied on back then strictly prohibited the use of funds for overseas travel or hiring more researchers.

“There were no foreign researchers around at the time. I remember one time I was asked to host a researcher from Germany. I spent an entire day showing him around. Somehow we managed to communicate with one another, but by the end of the day I had a terrible headache.”

That was not the only headache Nomoto encountered. Astronomer Hatanaka passed away when Nomoto was an undergraduate student at the University of Tokyo, leaving him to look for a new mentor to help him pursue his interest in star evolution. But no one at the university was studying it.

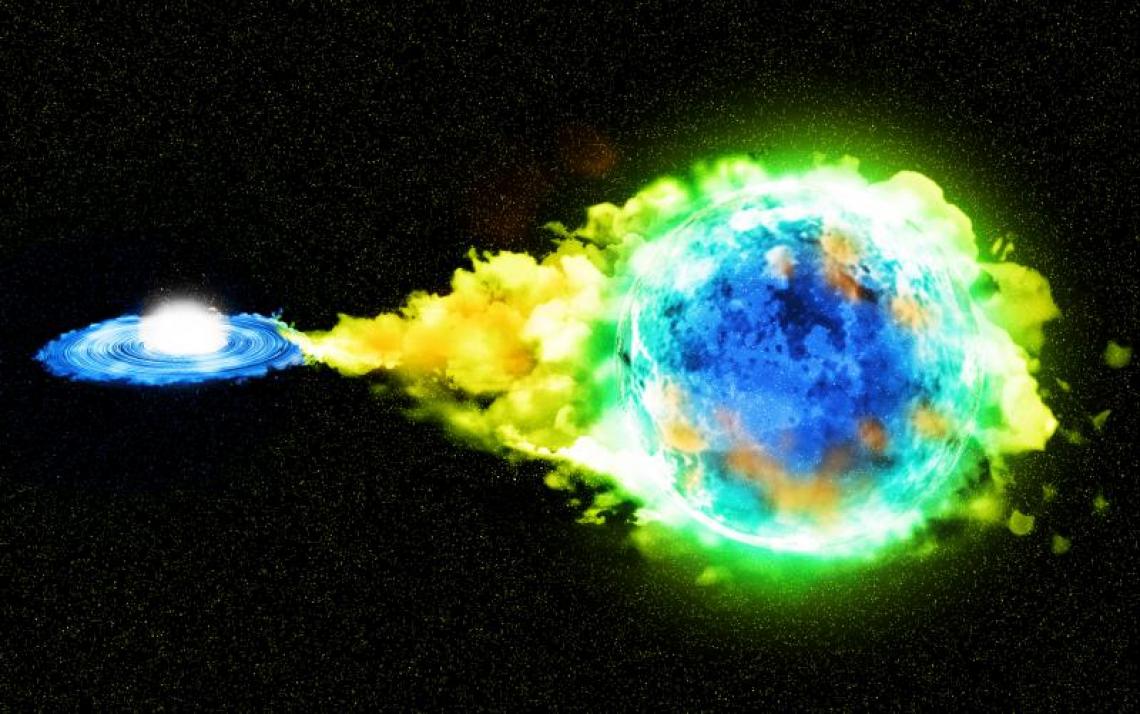

Shock waves from a supernova produce enormous amounts of ultraviolet light. Analysing the UV light can reveal the explosion mechanism in a supernova. Read the study.

Then, a chance meeting with astronomer Daiichiro Sugimoto, a protégé of pioneering astrophysicist Chushiro Hayashi, saved his academic ambition.

“Sugimoto was based in Nagoya University, but he taught at the University of Tokyo once a week. He would come into Tokyo on a Saturday, stay at the department’s lodging room, and then go home the next day. He would stay up all night having discussions with the students before going back to Nagoya. And that’s how we made a stellar evolution group at the university.”

Discovering opportunities turned out to be Nomoto’s ticket to furthering his career.

“In the beginning, I never thought of going overseas. I was scrambling to find a job. When I found a job at Ibaraki University, they happened to have a policy that allowed junior researchers to work overseas for a year or two on leave.

“At that time, Sugimoto had been at NASA for ten years, and he told me about postdoctoral positions there. I applied, and a few years later I was accepted to a position at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.”

Then began Nomoto’s strategy of taking advantage of the opportunities in front of him.

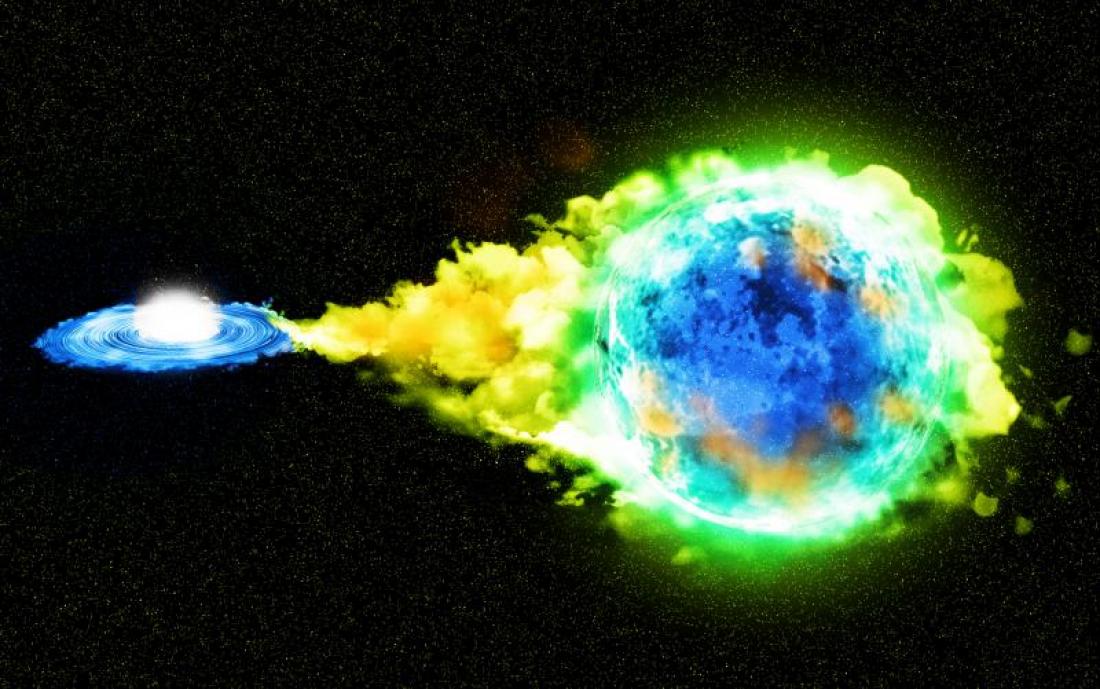

This is an artist's impression of a white dwarf receiving gases from a binary companion star. Here researchers ran simulations to find out why supernova explosions of some white dwarfs produce so much manganese and nickel. Read the study.

“The good thing about NASA was that it was very broad. There was a host laboratory I was based at, but there weren’t strict policies about what I had to do. So I thought, since I’m in the US, I’ll start going to research meetings.

“They didn’t give me money. A little maybe, but I remember writing letters everywhere to secure funding. If there was a conference, I would write a letter to the organizers asking for some travel funds.”

As Nomoto traveled, he started promoting his work with NASA, which led to more opportunities.

“I was studying how one type of supernova could produce lots of radioactive elements, which later helped find dark energy, and wrote a paper. A conference organizer in Italy read it and invited me to speak there. An American researcher from Stony Brook University heard my talk and invited me to apply for a one-year position at Brookhaven.”

Two years later, at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, Nomoto’s collaborative research involved studying gravitational collapses in explosions of very light stars.

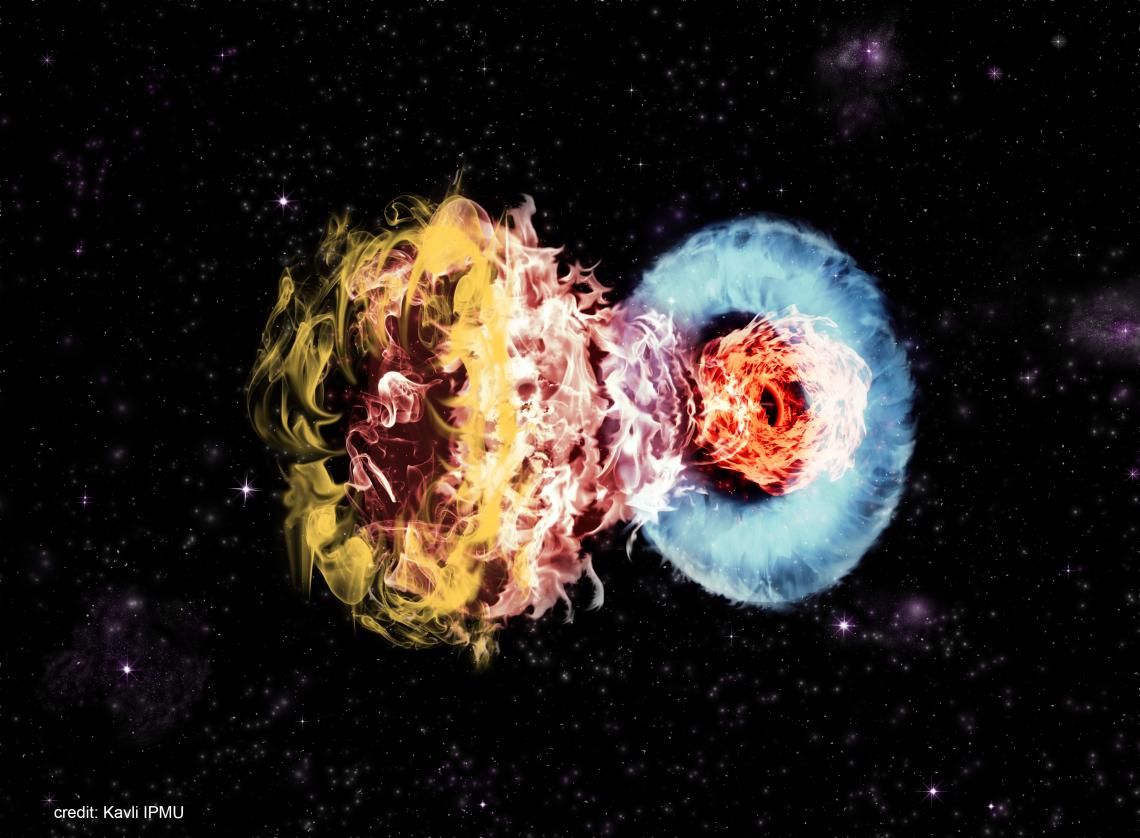

Scientists simulated the violent collisions between a supernova and its surrounding gas, which is ejected before an explosion, giving off an extreme brightness. This image shows a shock-interacting supernova with different velocity eruptions: the blue ring moves slowly, followed by the faster red-to-yellow gas. Read the study.

But as Nomoto began to give talks, some people started criticizing his work.

“I would give a talk and someone would say I was wrong. But it’s okay because then one of his collaborators would stand up for me."

From there, Nomoto found what worked best for furthering his research. The first thing was writing papers. The second was finding the gaps in the research, things that researchers in the US and Europe had missed, and filling in those gaps. In doing so, more people began to want to hear about Nomoto’s work, and this led to being able to go to more conferences.

He also found institutes that offer short research stays.

“Astronomical objects are so many and so distant that you must be able to collaborate with other astronomers.”

Over the years, Nomoto has seen Japan opening up to the international scene, triggering new research relationships that continue to this day.

“Allowing research funds to be used for international travel and for hiring researchers has been a game changer. It used to be that I had to leave the country to work with the best experimental researchers overseas to test my theories. Now experiments have become so much better in Japan that my rivals are traveling from the US to Japan to test their theories with Japanese experiments.”

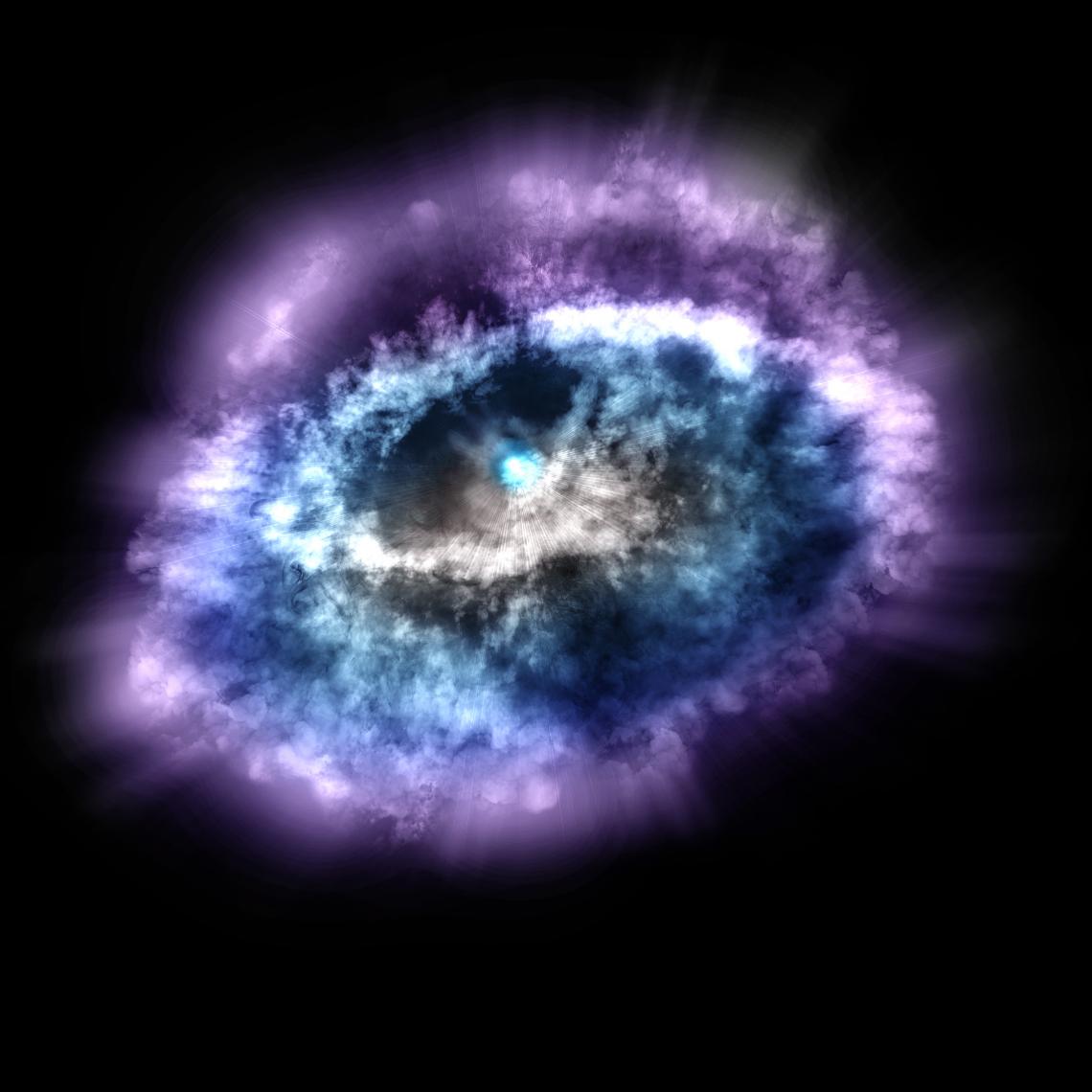

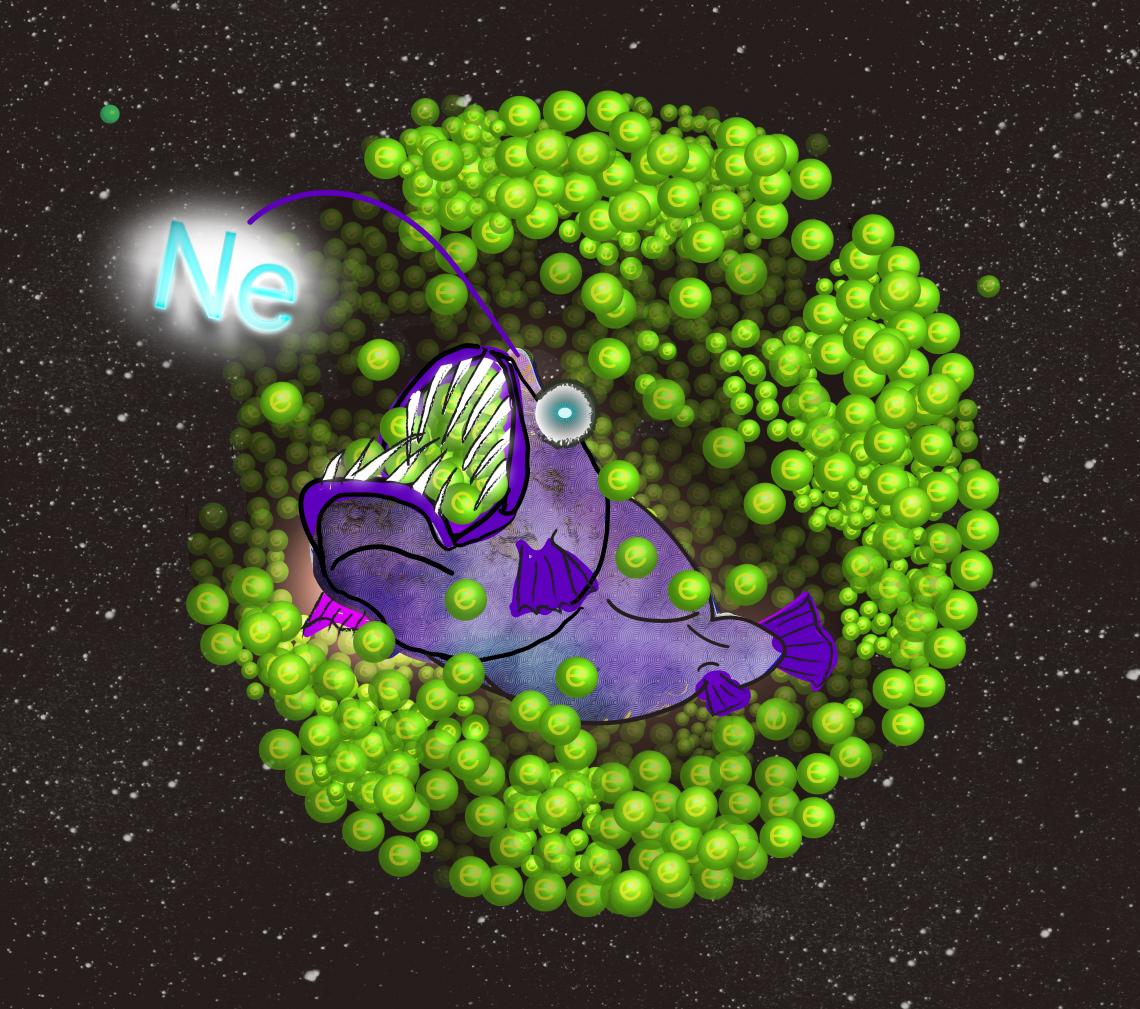

Prof Nomoto and colleagues found that the neon in the very high density center of a certain massive star can eat so many electrons in the core that the star collapses into a neutron star, producing a supernova. This is an artist’s impression of an imaginary deep-sea fish "football-fish" with a neon-sign eating away at the electrons inside a stellar core. Read the study.

Further information

Visiting Senior Scientist Ken'ichi Nomoto

[email protected]

Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe

The University of Tokyo

We welcome you to reproduce articles in Asia Research News 2023 provided appropriate credit is given to Asia Research News and the research institutions featured.