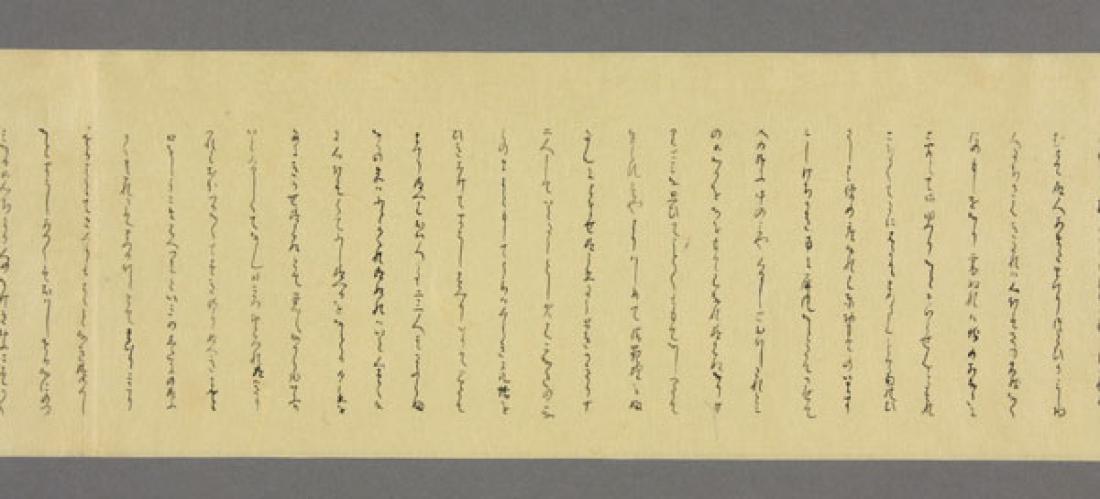

The Tale of Genji (pocket-sized scroll from the mid Edo period) Chapter 47: Trefoil Knots (Agemaki) (Waseda University Library)

It was on 10 January of this year, and I was attending a regular monthly reading of the Kawachibon manuscript of The Tale of Genji at a friend’s house. The manuscript was formerly owned by the Owari branch of the Tokugawa clan; we read from the photographic reproduction published by Yagi Shoten in 10 volumes between 2010 and 2013. We never discuss the meaning of Genji at these gatherings; instead, the point is to simply to practice reading the old cursive script, to decipher those unbroken stretches of kana. Last year, we finally got to the Ten Uji Chapters in the second half of the work. On this day, group members were each reading four pages of the Trefoil Knots (Agemaki) chapter in turn. We came to the part where Ōigimi has taken ill, with my friend reading aloud. As “a perpetual reading of the Lotus Sutra began,” Kaoru “lifted her standing curtain and slipped inside it a little” to look at Ōigimi, who is lying down.

“Will you not let me at least hear your voice?” he pleaded, taking her hand to rouse her.

“I would, but it is difficult to talk,” she murmured under her breath.

“You have not come for so long. I thought I might go in the end without seeing you again, and I was very sorry.”

“To think that I kept you waiting so long!” He was sobbing now. Her forehead felt a little warm.

Royall Tyler, trans., The Tale of Genji (New York: Viking, 2001), p. 905.

Although my friend had struggled with the text up to this point, the scene was so heart-wrenching that tears welled up in her eyes and rolled down her cheeks, blurring the words on the page, and her voice caught in her throat. For my part, because I’m not very good at reading the old cursive syllabary, I can’t say that I fully understood this exchange between Kaoru and Ōigimi; and yet, the sight of my friend weeping drew forth my own tears. The words she spoke as she fought to maintain composure were powerful. “How extraordinary,” she said, “that a novel so old can still bring us to tears.”

I believe that my friend spoke the truth that day. The Tale of Genji is a massive work composed by a woman who lived a thousand years ago. Over the hundreds and hundreds of years since then, thousands have continued to read it. There is no other example of a work of literature so old yet still treasured as a novel by modern readers.

I was a second-year university student when I first read The Tale of Genji, in an English translation of course. And though it has been over thirty years since it first captivated me, I have continued to read The Tale of Genji over and over in many different forms since then. In all this time I have never once tired of it—and never felt that I completely understood it. I continue to read it to this day.

When I talk to my students about The Tale of Genji, I am surprised to find that they are typically only familiar with parts of it—and even those portions they’ve only “studied” for a university exam. They haven’t truly read them. I can’t help but find it tragic that a globally recognized masterpiece is being approached as if were a tedious chore. The Tale of Genji is unquestionably more fascinating than an academic text that must be studied. And not just because it has the touching scene that brought my friend to tears as she read it aloud. It also contains delightful characters like the professor’s daughter (Hakase no musume) in The Broom Tree (Hahakigi) chapter—or Ōmi no Kimi, who appears in The Pink (Tokonatsu) chapter. Readers are charmed by Oborozukiyo, daughter of the Minister of the Right, who burned with passion from a secret love affair with Genji. And we are inspired by the fortitude she demonstrates in her later life.

I could easily go on, as there is truly no end to The Tale of Genji’s appeal. I strongly encourage everyone to read it from beginning to end. Choose a modern Japanese version, or one in translation—whichever you think you will enjoy the most. Japanese versions by Yosano Akiko, Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, and Enchi Fumiko are readily available; writers like Hashimoto Osamu and Setouchi Jakuchō have also put out paperback editions that are easy to obtain. Among the Western languages, complete translations are available in English, French, German, Italian, Russian, and Dutch, while two full versions exist in both Chinese and Korean. (For more information, visit http://www.gayerowley.com/teaching/genji-bibliography/)

The Tale of Genji whisks us away to another world, telling us something to this day. It is now nearly spring. Why not pick up The Tale of Genji once your exams are over and you have some extra time? Let the voice of the narrator fill your ears. You are sure to discover that this masterwork holds something unique and personal for you as well.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gaye Rowley

Professor, Faculty of Law, Waseda University

[Profile]

Gaye Rowley was born in Australia. She graduated from the Faculty of Asian Studies, Australian National University in 1984, and in 1987 completed her master’s degree in Japanese literature at Japan Women’s University. She went on to study at the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Cambridge, where she was awarded her PhD in 1995. She took up her current position in the Faculty of Law, Waseda University in 2001. She specializes in Japanese literature, particularly the reception of The Tale of Genji, and women’s history. Her major works include Yosano Akiko and The Tale of Genji (2000), The Female as Subject: Reading and Writing in Early Modern Japan (co-authored, 2010), and An Imperial Concubine’s Tale (2013).