(This is a republication of an original article written by IPS Research Economist, Dr Asanka Wijesinghe and IPS Research Assistant, Chathurrdhika Yogarajah. Access the original blog here)

Bangladesh – Sri Lanka Trade: The Current Status

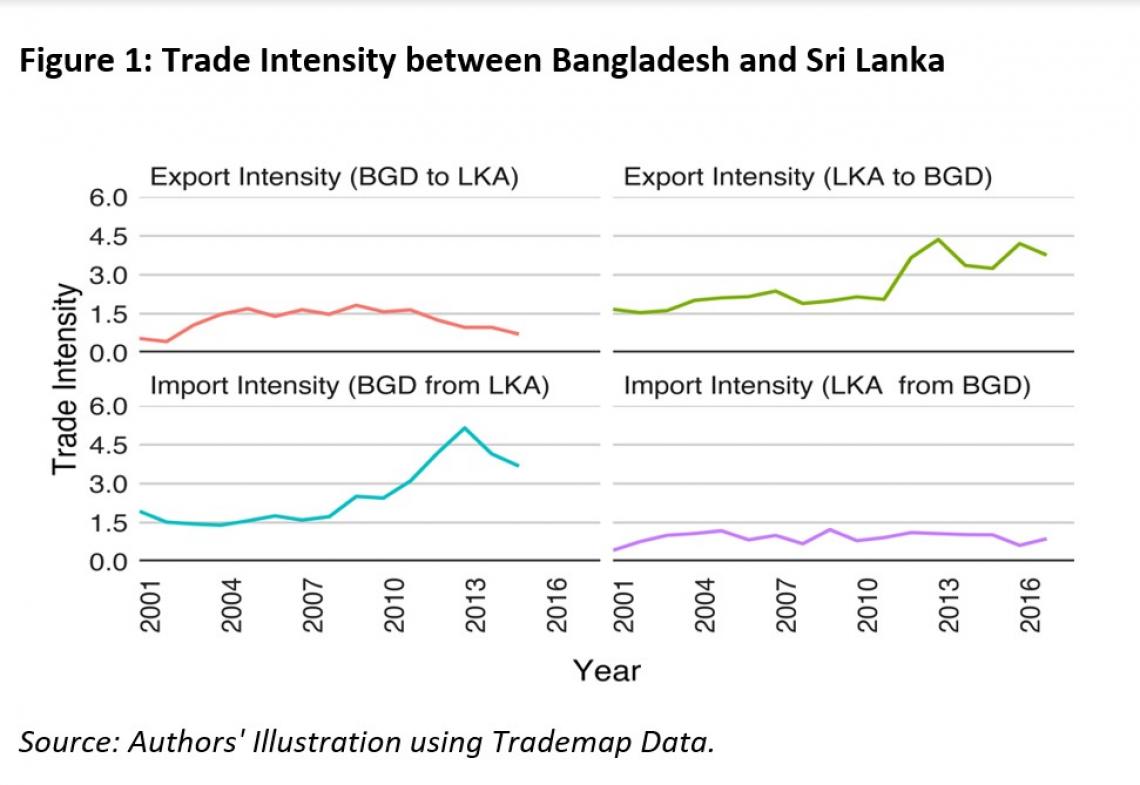

In 2018, when discussions on a PTA began to firm up, Sri Lanka’s exports to Bangladesh were USD 133 million, while imports from Bangladesh were USD 37 million. Despite the low trade volume, Sri Lanka’s exports to Bangladesh have grown (Figure 1). In addition, Sri Lanka records a bilateral trade surplus with Bangladesh, which is encouraging given the country’s trade deficit concerns. However, weak growth of exports from Bangladesh to Sri Lanka can be seen from 2001 to 2016 (Figure 1).

The current trade deals between the two countries are still partially restrictive. Both countries keep a sensitive list of products that are not eligible for tariff cuts. Sri Lanka maintains a list of 925 products sanctioned by SAFTA (South Asian Free Trade Area) while Bangladesh keeps 993 products. Sri Lanka’s sensitive list covers USD 6.2 million or 23.8% of imports from Bangladesh. The sensitive list of Bangladesh covers USD 77.6 million or 62% of imports from Sri Lanka. Thus, the elimination of sensitive lists may benefit Sri Lanka more.

Motivations and Possibilities of a Trade Deal

Theoretically, bilateral alliances deepen trade by removing weaknesses in existing multilateral trade arrangements. A trade deal between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka can simplify trade regulations further. In addition, Bangladesh needs alternative preferential access as graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status will take away preferential access to its key markets. For Sri Lanka, increasing bilateral participation in production value chains, especially in the textiles sector, might be an economic motivation. Financial support extended by Bangladesh to manage Sri Lanka’s foreign currency pressures might be a political motivation for a trade deal.

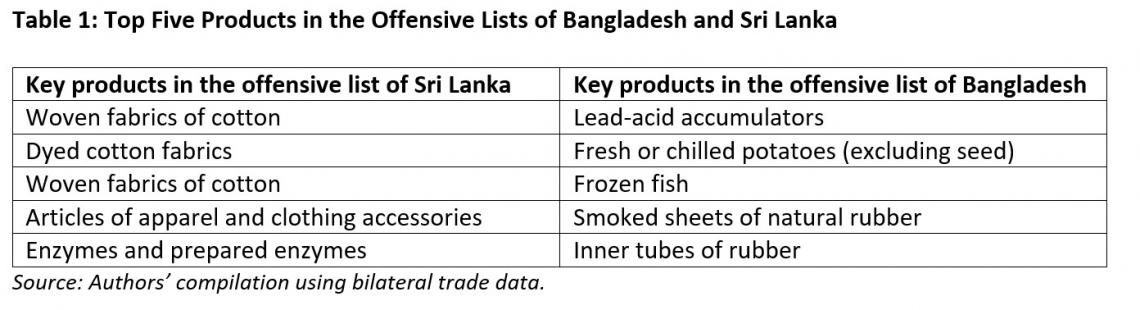

Eliminating sensitive lists can lead to trade creation, although it may not happen due to political and economic reasons. When it comes to tariff cuts, both countries will act defensively as certain products in the sensitive lists are vital for employment and revenue generation. Thus, the success of a trade deal depends on how many products with high export potential are under its purview. In this direction, a group of products with specific characteristics can be identified as an offensive list. For example, Sri Lanka’s offensive list includes products that Bangladesh imports from anywhere in the world, produced by Sri Lanka with a capacity for expansion. Sri Lanka has a comparative advantage in exporting that good, and Bangladesh already has a tariff on the product.

Export Gains from Tariff Elimination

If tariffs on the sensitive lists are eliminated, there will be modest export gains for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in absolute terms. Sri Lanka will gain USD 24.7 to 49.7 million of exports to Bangladesh, while Bangladesh will gain USD 2.1 to 4.5 million of exports to Sri Lanka. Potential export gains are given in a range due to assumptions on elasticity values used in the partial equilibrium model. Elimination of sensitive lists will generate a higher tariff revenue loss to Bangladesh, ranging between USD 13.5 million to USD 19.1 million. By contrast, Sri Lanka’s revenue loss will be slight at USD 1.4 million to USD 1.9 million.

Whatever the arrangement, it is crucial to include the products with high export potential in the offensive lists (See Table 1 for the major products). Out of 39 products in Bangladesh’s offensive list, 21 are intermediate goods, while 18 are consumption goods. Similarly, 75 out of 115 products in Sri Lanka’s offensive list are intermediate goods. Tariff cuts on intermediate products may induce fragmented production between two countries, which would harness country-specific comparative advantages. Major intermediate goods in the offensive lists are dyed cotton fabrics, cartons, boxes, and cases, plain woven fabrics of cotton, denim, natural rubber, and smoked sheets of natural rubber (Table 1).

Economics of a PTA between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka

The ex-ante estimates predict modest gains for Sri Lanka and Bangladesh in absolute terms, even after completely removing the sensitive list. But complete removal is politically challenging for both countries. Moreover, Bangladesh as an LDC may expect special and differential (S&D) treatment. Thus, the outcome can be a limited PTA in line with weaknesses in existing trade agreements governing South Asian trade. The impact on trade of regional trade agreements in force is negative primarily due to stringent general regulatory measures, including rules of origin (ROO), sensitive lists, and prolonged phasing-in. Given that the estimated modest economic gains of a Bangladesh-Sri Lanka PTA do not justify a trade deal that requires substantial resources for negotiations, the PTA should have fewer regulatory measures and tariff concessions for the products on the offensive lists to maximise the economic benefits of a PTA between the two countries.