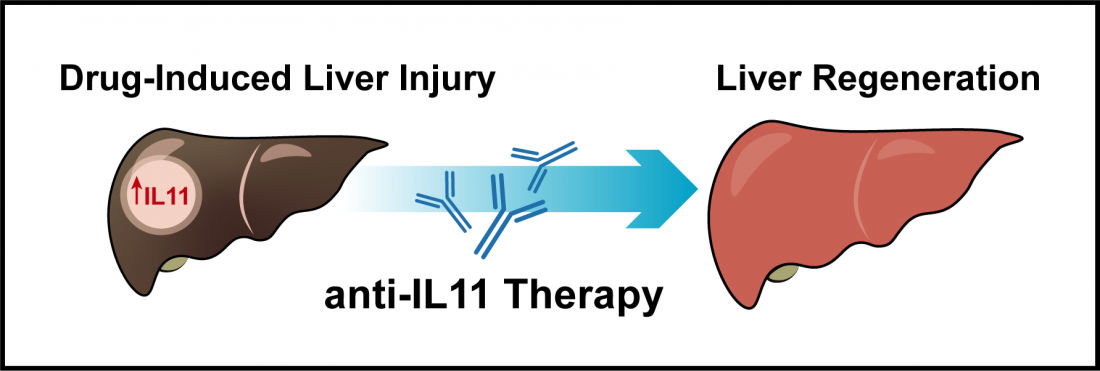

Antibody therapies that neutralise IL11, a liver toxin, protect the liver from drug-induced damage and promote regeneration.

Singapore, 18 Jun 2021 – Scientists at Duke-NUS Medical School and National Heart Centre Singapore (NHCS), in collaboration with colleagues in Singapore and the UK, have shown that the human form of the signalling protein interleukin 11 (IL-11) has a damaging effect on human liver cells—overturning a prior hypothesis that it could help livers damaged by paracetamol poisoning. The finding, published last week in Science Translational Medicine, suggests that blocking IL-11 signalling could have a restorative effect.

Paracetamol, also called acetaminophen, is a widely available over-the-counter painkiller, and an overdose can lead to serious liver damage and even death. It is the most common pharmaceutical agent involved in toxic exposure in Singapore, while in the UK, 50,000 people a year show up at emergency departments with paracetamol poisoning. They can be treated with a drug called N-acetylcysteine if administered within eight hours of overdose. Any longer, however, and the only recourse may be a liver transplant.

To find treatments for the condition, scientists have been studying it in mice. Their investigations have shown that excessive doses of paracetamol deplete liver antioxidants. This leads to damage of mitochondrial proteins, triggering a cascade of events that lead to liver damage and liver cell death. Further studies showed that administration of anti-IL11 therapy in the form of an antibody drug not only reversed liver damage, but also supported liver regeneration and promoted survival in mice with liver injury. This led to the idea that anti-IL11 therapy could help treat humans with paracetamol poisoning.

“We recently found that IL-11 was actually detrimental for liver cell function in a fatty liver disease called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH),” said Assistant Professor Anissa Widjaja, from Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases (CVMD) Programme, the lead author of the study. “This made us want to look in more detail at what was happening in mouse models of paracetamol toxicity.”

Employing an animal model conducted according to the National Advisory Committee for Laboratory Animal Research (NACLAR) guidelines, they found high serum levels of IL-11 in mice with paracetamol toxicity. Further investigations revealed that IL-11 was involved in activating pathways that led to liver cell death. Surprisingly, they found that mouse livers responded differently according to whether they were given human or mouse IL-11. The human form had a protective effect against liver damage while the mouse form caused liver cell death. When human IL-11 was administered in mice with paracetamol toxicity, it competed with the endogenous mouse IL-11, blocking its receptor. It was this blocking effect that protected against liver damage. Administering same-species IL-11 was damaging because it did not result in this competition and the resulting blocking effect.

“This means that IL-11 is actually a liver toxin,” said Professor Stuart Cook, the senior author of the study, who is the Tanoto Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre and Duke-NUS’ CVMD Programme, and Senior Consultant at the Department of Cardiology at NHCS. “We found that blocking its cell receptors with an antibody can help the liver regenerate after it has been injured. This discovery could have implications for treating drug-induced liver failure, which can cause death if a liver transplant is not possible.”

The study adds to the growing body of research on IL-11, led by Prof Cook, a leading expert who has dedicated years of study to this important signalling protein. In 2017, he co-founded Singapore-based Enleofen Bio as a spin-out from NHCS, SingHealth and Duke-NUS with the aim of developing first-in-class antibody therapeutics for the treatment of fibro-inflammatory human diseases. In 2019, Boehringer Ingelheim, a leading global pharmaceutical company in the treatment of fibrotic diseases and in therapeutic antibodies took an exclusive license to Enleofen’s anti-IL11 platform.

Professor Patrick Casey, Senior Vice-Dean for Research at Duke-NUS, commented, “New insights from fundamental research enable scientists to not only test hypotheses, but also course-correct when the evidence overturns prior assumptions. Professor Cook and his team are among the leading experts on IL-11, and their latest findings yet again advance our understanding in this field of research.”

The research team is now investigating whether IL-11 can stand in the way of the regeneration of other organs, like the kidneys, and whether it is involved in the loss of tissue function with advancing age.