The biodiversity of marine communities in the Pacific Arctic under future climate change scenarios highlights profound changes relative to their present patterns. Alterations in marine species distributions in response to warming and sea ice reduction are likely to increase the susceptibility and vulnerability of Arctic ecosystems. The findings, published by Hokkaido University researchers in the journal Science of the Total Environment, also suggest that there will be potential impacts on the ecosystem function and services.

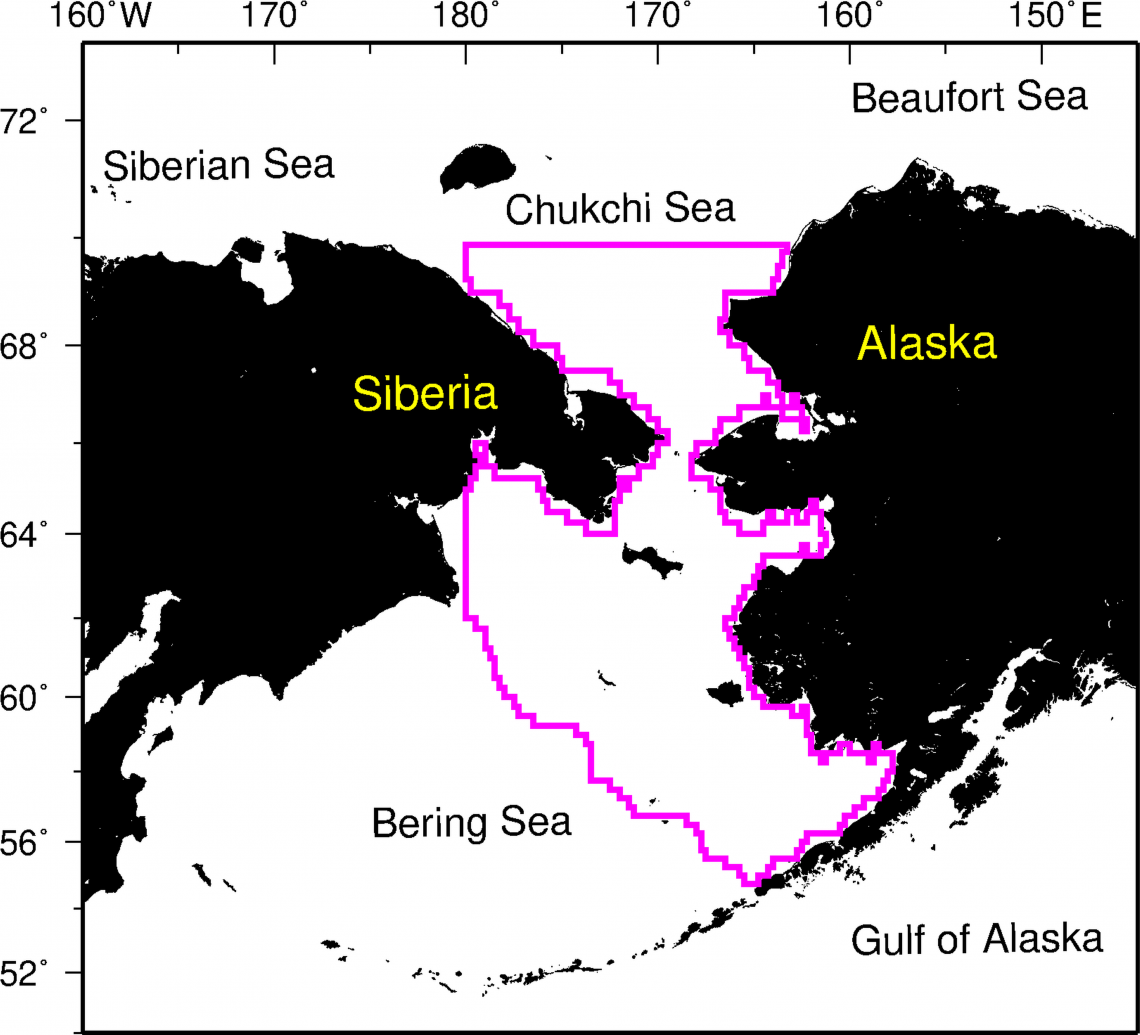

Fisheries oceanographer Irene Alabia of Hokkaido University’s Arctic Research Center along with colleagues in Japan and the US investigated how future climate changes will impact the marine biodiversity in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. These seas extend from Alaska to Russia in the northern Pacific and southern Arctic oceans.

Geographic map of the Pacific Arctic region, highlighting the study area in purple contour. (Irene D. Alabia, et al., Science of The Total Environment, supplementary file, July 15, 2020).

“This area forms a ‘biogeographical transition zone’: a biodiversity-rich region covering two distinct areas with specific features that encourage the coexistence of species living at or close to their distribution limits,” explains Alabia. “These zones are vulnerable to climate warming, and climatic disruptions can create favorable conditions for the shift of warm-water species into previously colder-water zones.”

Scientists are interested in understanding how species in biogeographical transition zones are responding to climate changes and other human impacts. This information could help in conservation planning, fisheries management, and in studying the role of evolutionary history in shaping currently existing communities.

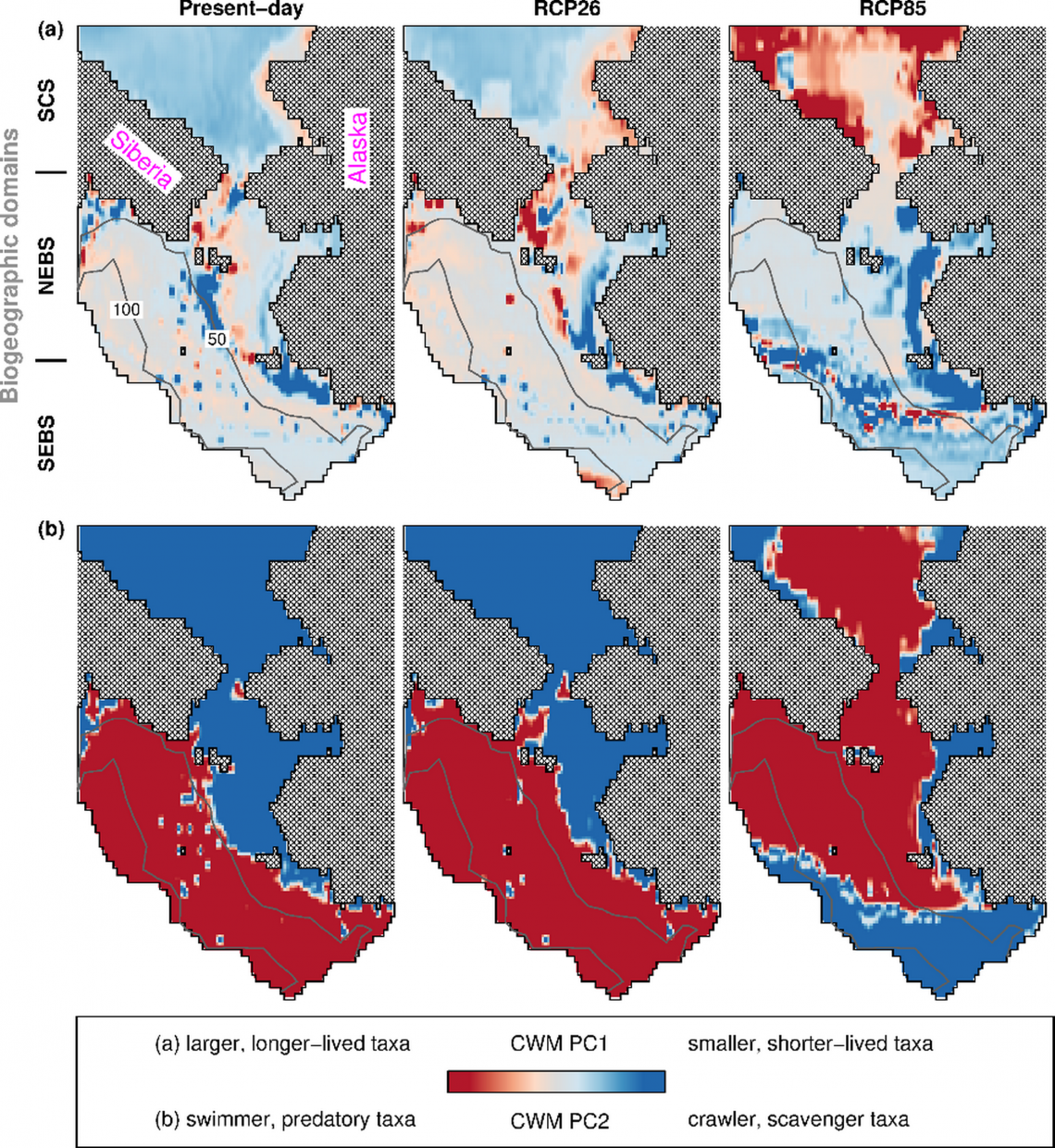

Alabia and her team mapped the present and future spatial distributions of 26 fish and invertebrate species in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Using species records, sea surface temperature, and sea ice concentration data, the authors developed species distribution models to predict the distributional ranges under the present-day (1993-2017) and future (2026-2100) climate conditions. From the model outputs, the changes in species richness and compositional diversity in terms of species’ phylogeny and functional traits between time periods and across contrasting levels of warming were elucidated.

The findings suggest that larger, longer-lived and more predatory fish and invertebrates will expand their ranges towards the pole in response to warming waters and sea ice free conditions by the end of the 21st century. These poleward shifts could alter the structure, composition and functions of future Arctic communities, which are currently dominated by smaller and short-lived species. The future species pool in the Arctic waters will also have more similar functions within the ecosystem, impacting regional food webs. It is also likely that there will be considerable socioeconomic impacts, as commercially important species shift northwards, which could increase operational fishing costs.

Spatial distribution of functional traits of marine communities in the Eastern Bering and Chukchi Seas for the present-day (left panels) and late-century periods under low (middle panels) and high (right panels). Larger, longer-lived (top row) and more predatory (bottom row) fish and invertebrates will expand northwards as the seas warm; how far their ranges expand is determined by the extent of warming. (Irene D. Alabia, et al., Science of The Total Environment, July 15, 2020).

“These projected impacts are expected to raise challenges for ocean governance, conservation and resource management of shifting fisheries,” says Alabia. “Our results provided glimpses of potential futures of the Arctic marine ecosystems, nonetheless, and some of these ecological shifts are already being documented. As such this highlights the need for continued monitoring and improving climate-ready strategies to buffer climate change impacts and maintain the integrity and functioning of vulnerable ecosystems.”