The Japanese icebreaker Shirase near the tip of the Shirase Glacier during the 58th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition.

This story is featured in the Asia Research News 2021 magazine. Read in ISSUU (above) or full text and images below.

Hokkaido University scientists have identified an atypical hotspot of sub-glacier melting in East Antarctica. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, could further understandings and predictions of sea level rise caused by mass loss of ice sheets from the southernmost continent.

The 58th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition had a very rare opportunity to conduct ship-based observations near the tip of East Antarctic Shirase Glacier when large areas of heavy sea ice broke up, giving them access to the frozen Lützow-Holm Bay into which the glacier protrudes.

“Our data suggests that the ice directly beneath the Shirase Glacier Tongue is melting at a rate of 7-16 metres per year,” says Daisuke Hirano, a physical oceanographer at Hokkaido University’s Institute of Low Temperature Science. “This is equal to or perhaps even surpasses the melting rate underneath the Totten Ice Shelf, which was thought to be experiencing the highest melting rate in East Antarctica, at a rate of 10-11 metres per year.”

Daisuke Hirano (centre) with a helicopter pilot (left) and a field assistant (right) having lunch on the floating Shirase Glacier Tongue.

The Antarctic ice sheet, most of which is in East Antarctica, is Earth’s largest freshwater reservoir. If it all melts, it could lead to a 60-metre rise in global sea levels. Current predictions estimate global sea levels will rise one metre by 2100 and more than 15 metres by 2500. Thus, it is very important for scientists to have a clear understanding of how Antarctic continental ice is melting, and to more accurately predict sea level fluctuations.

Most studies of ocean–ice interactions have been conducted on the ice shelves in West Antarctica. Ice shelves in East Antarctica have received much less attention, because the water cavities beneath most of them were thought to be cold, protecting them from melting.

During the research expedition, Hirano and his collaborators collected data on water temperature, salinity and oxygen levels from 31 points in the area between January and February 2017. They combined this information with data on the area’s currents and wind, ice radar measurements, and computer modelling to understand ocean circulation underneath the Shirase Glacier Tongue at the glacier’s inland base.

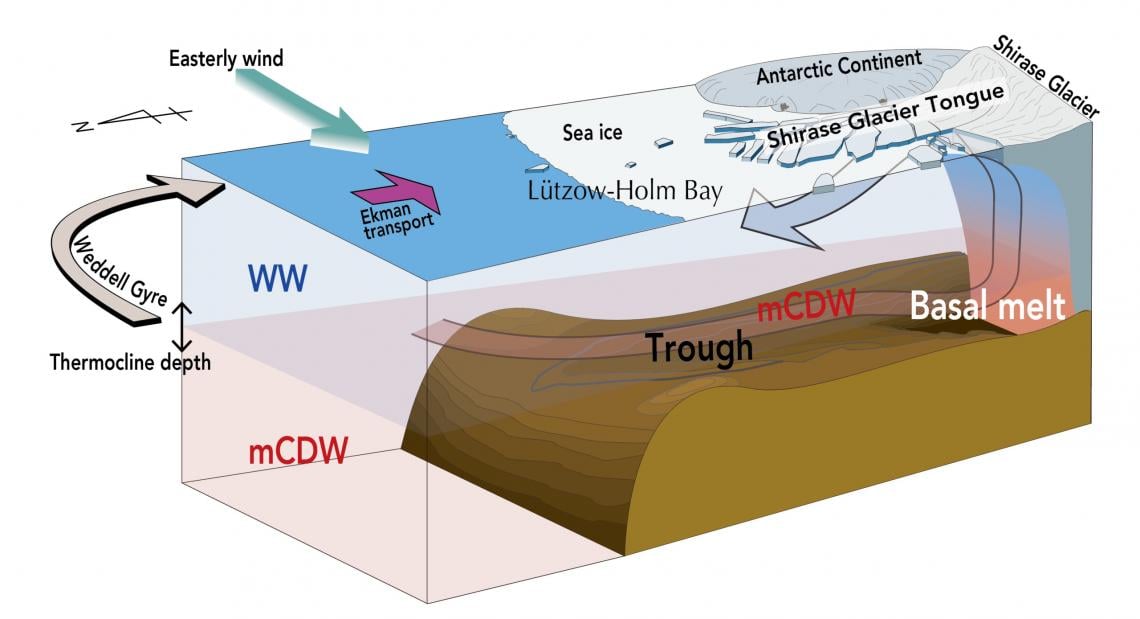

The scientists’ data suggests the melting is a result of deep, warm water flowing inwards towards the base of the Shirase Glacier Tongue. The warm water moves along a deep ocean trough and then flows upwards along the tongue’s base, warming and melting the ice. The warm waters carrying the melted ice then flow outwards, mixing with the glacial meltwater.

Warm water flows into Lützow-Holm Bay along a deep underwater ocean trough and then flows upwards along the tongue’s base, warming and melting the base of Shirase Glacier Tongue.

The team found this melting occurs year-round, but is affected by easterly, alongshore winds that vary seasonally. When the winds diminish in the summer, the influx of the deep warm water increases, speeding up the melting rate.

“We plan to incorporate this and future data into our computer models, which will help us develop more accurate predictions of sea level fluctuations and climate change,” Hirano says.

Further information

Assistant Professor Daisuke Hirano

[email protected]

Institute of Low Temperature Science

Hokkaido University