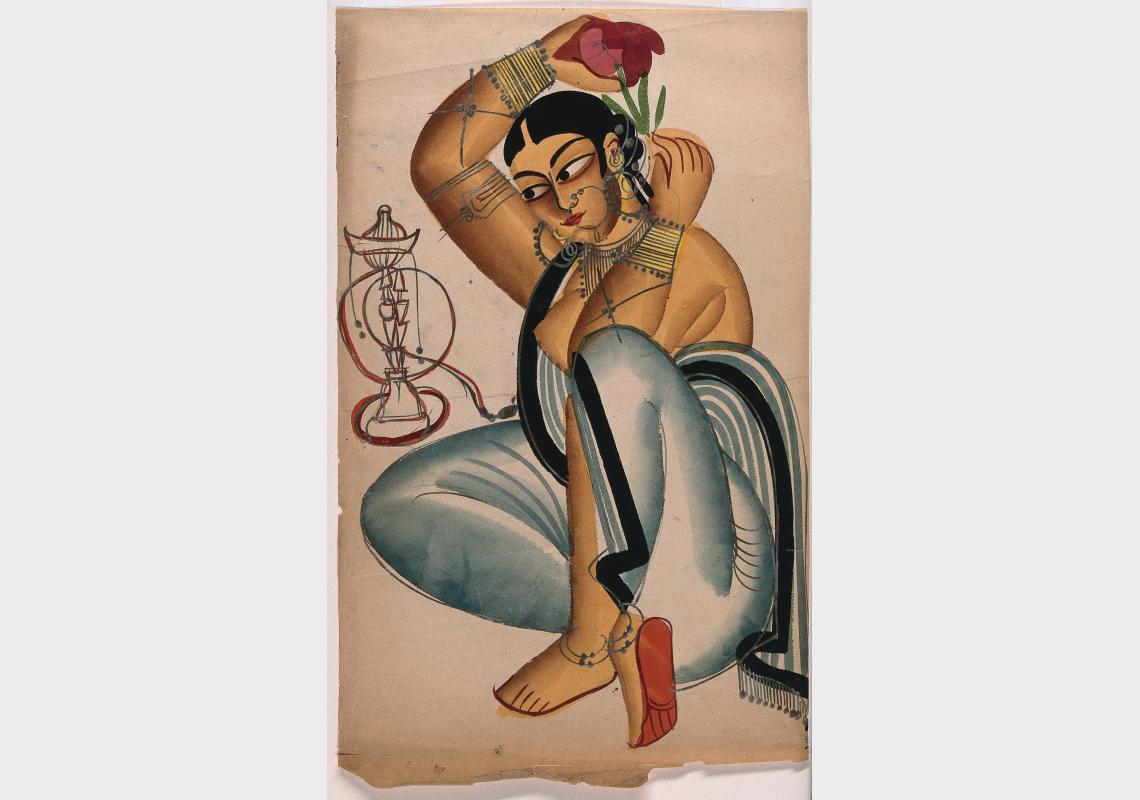

A Courtesan Arranging a Flower in Her Hair, India, c. 1800s, Gouache on paper.

A tradition of watercolour painting that originated in Calcutta (now Kolkata), Kalighat painting was practised by artisans from the Patua community between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century. The name derives from the city’s Kalighat temple, around which the painters had established their business, and the paintings were known for their bright colours, sweeping brush strokes and strong lines. Though these paintings were originally intended to be souvenirs for devotees visiting the temple of Kali and featured primarily Hindu imagery, they expanded over time to include other religious traditions as well as socio-political commentary.

Some scholars believe that the tradition can be traced to the 1830s or earlier when Patua artisans first moved to the city and began making paintings around the temple, while others argue that the thematic and visual characteristics that are more definitive of Kalighat painting, such as political caricatures, hairstyles and ornaments, only go as far as the 1850s. It is, however, broadly accepted that Kalighat painting reached its peak around the mid 1870s and began to decline after the late 1880s, owing to the rising popularity of photography and printing technology imported from England and Germany.

Unlike the sequential narratives of the patachitras, each Kalighat painting depicted a single and simplified scene, usually featuring opaque figures on neutral backgrounds. The paintings were made on mill-paper treated with a paste of lime, on which watercolours were dabbed using a large brush or a rag. The pigments used were derived from a mix of natural and industrial sources, including black from lampblack, red from lead, yellow from arsenic and blue from indigo. The black outline of the forms was drawn using a pencil or a brush made from squirrel or goat hair, after which paint was reapplied to the edges that needed shading. The creation of a Kalighat painting was often a family affair, with different members completing different steps of the process.

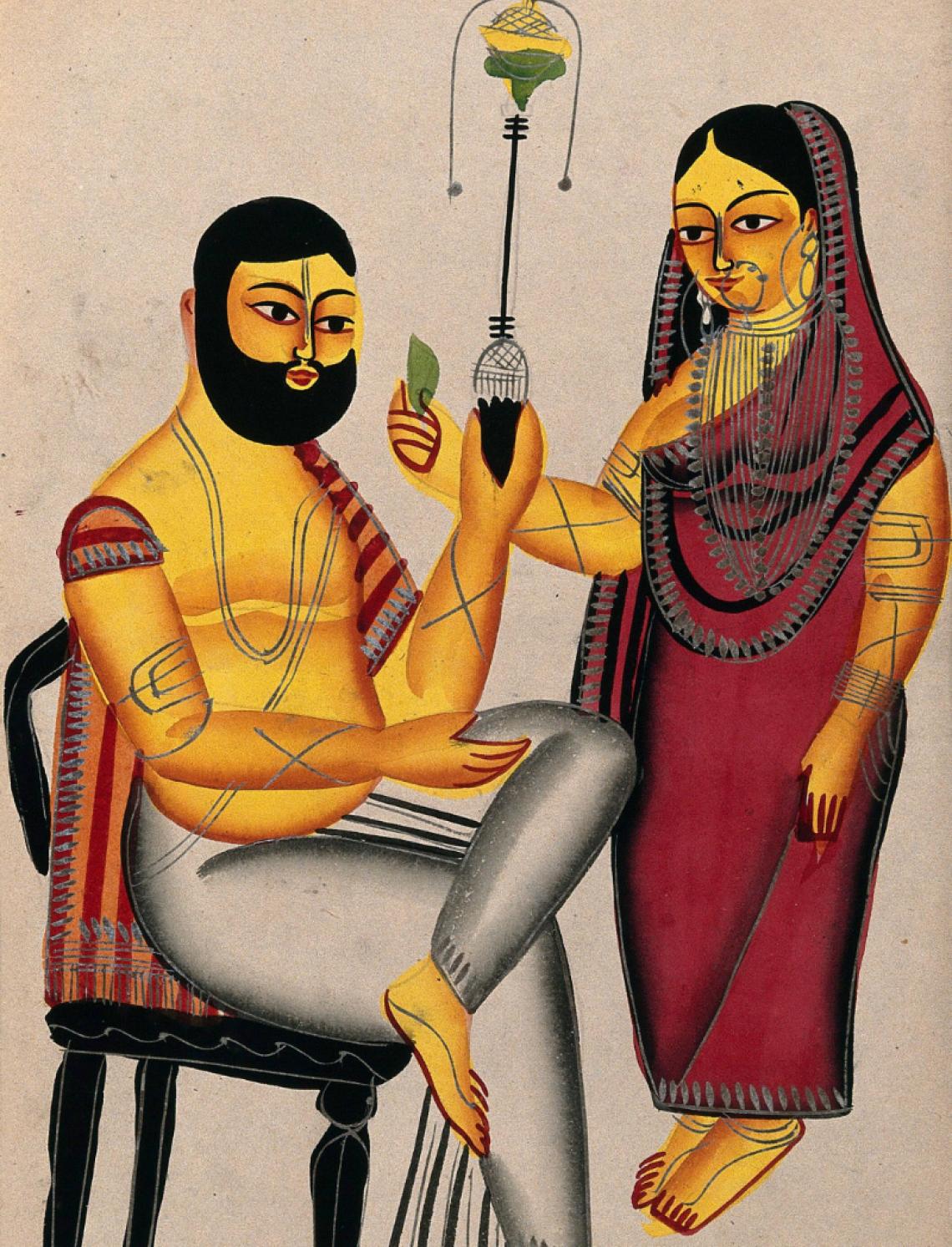

The Tarakeshwar Murder: Elokeshi Offers a Betel–Leaf to the Seated Mahant, Watercolour drawing with silver.

The key characteristics of the Kalighat style are the rounded, tapering limbs and pointed faces with small mouths and elongated, almond-shaped eyes. The neck and limbs may be bent at sharp angles or drawn as fluid curves, allowing the figures to have dynamic poses. Only the human figures are drawn with heavy shading and outlines, giving them a three-dimensionality that was not applied to the backdrop. This removed depth from the painting, made the characters appear more radiant, and sharply separated them from the background. In the case of many secular paintings, the background was omitted altogether.

In the early 1800s, Calcutta –– the then capital of British India –– was developing into a thriving centre of industry and tourism, attracting, among others, migrant groups of rural artisans and craftspeople. This included the Patuas, who traditionally painted over twenty-feet long narrative scrolls known as patachitras. Costly and cumbersome to carry, these patachitras found few takers among pilgrims visiting the city, compelling the artisans to create smaller, less detailed but more portable images, which would come to be known as the Kalighat pats. The number of such visitors increased as trains began to connect more parts of the country to urban areas in the nineteenth century. Partly because their patronage came primarily from ordinary people, and partly because Patua painters were known for sometimes using their craft as a documentary tool, Kalighat paintings developed a reputation for keeping up with the visual culture of the time.

Based on the broadest date range assigned to the tradition by scholars, the development of Kalighat painting can be divided into three distinct phases. The first phase covers the period immediately after the patua artists moved to the city, when the paintings were heavily influenced by the patachitra tradition. During this time, the Kalighat pats were sold as religious souvenirs for pilgrims at the temple, and therefore, portrayed religious icons such as Kali, Durga, Lakshmi and Saraswati, as well as related deities such as Ganesh, Krishna and Shiva who feature in the myths around these goddesses, and scenes from Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Although the paintings were mainly religious, secular elements were often incorporated for added appeal, including depicting deities wearing Western shoes or holding violins instead of veenas. As the style gained popularity, Kalighat painting moved into the second phase, with groups other than the Patuas taking up the profession. Soon after, the paintings began to incorporate Islamic and Christian scenes and iconographies, including Islamic saints, angels and tazias.

During the third and final phase –– from the mid-nineteenth century onwards –– Kalighat painting began moving away from religious themes and icons to depict more contemporary, humorous and satirical subjects. The artworks, which had grown popular among the migrants and non-elites of the city, began reflecting socio-cultural and political themes, ranging from topics such as courtesan culture, domestic pets, murder trials, horse racing and wrestling, among others. A frequent topic in this category was women’s emancipation: the education, legal sanctions and increased independence of upper class Indian women in the nineteenth century was satirically shown in paintings depicting husbands cowering before their wives, possibly as opportune references to Durga or Kali. The paintings also discussed colonial politics in the subcontinent, criticising the British government’s Indian collaborators through caricatures of complacency and greed, while praising iconic freedom fighters like Rani Lakshmibai, also known as Rani of Jhansi, and Tipu Sultan. Despite its popularity, the Kalighat style was subjected to severe criticism from British artists and Bengali elites for its politically charged subject matter and perceived non-conformity to Victorian modes of representation.

Kalighat painting gained international attention in 1895, when Maxwell Sommerville donated fifty-seven paintings to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, USA. Following this, in 1917, Rudyard Kipling donated a collection of 233 Kalighat paintings to the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK, which later developed into the largest collections of Kalighat paintings in the world. Other notable collections of Kalighat paintings can be found at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK; the British Library, London; the Naprstek Museum, Prague, Czech Republic; and the Pushkin Museum of Graphic Arts, Moscow, Russia. Within India, the most prominent Kalighat collections can be found at museums across Kolkata, including the Victoria Memorial Hall; the Indian Museum; the Gurusaday Museum; the Birla Academy of Art and Culture; the Asutosh Museum; and Kala Bhavan, Visva-Bharati University, Shantiniketan.

As most Kalighat paintings were undated, unsigned and developed by multiple individuals, the names of most artists remain unknown. The last well-known Kalighat artists, Nibaran Chandra Ghosh and Kali Charan Ghosh, passed away in 1930. However, Kalighat paintings were instrumental in influencing subsequent generations of Indian artists, most notably Jamini Roy, and more recently the Midnapore-based contemporary artist Uttam Chitrakar.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and a Blog, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.