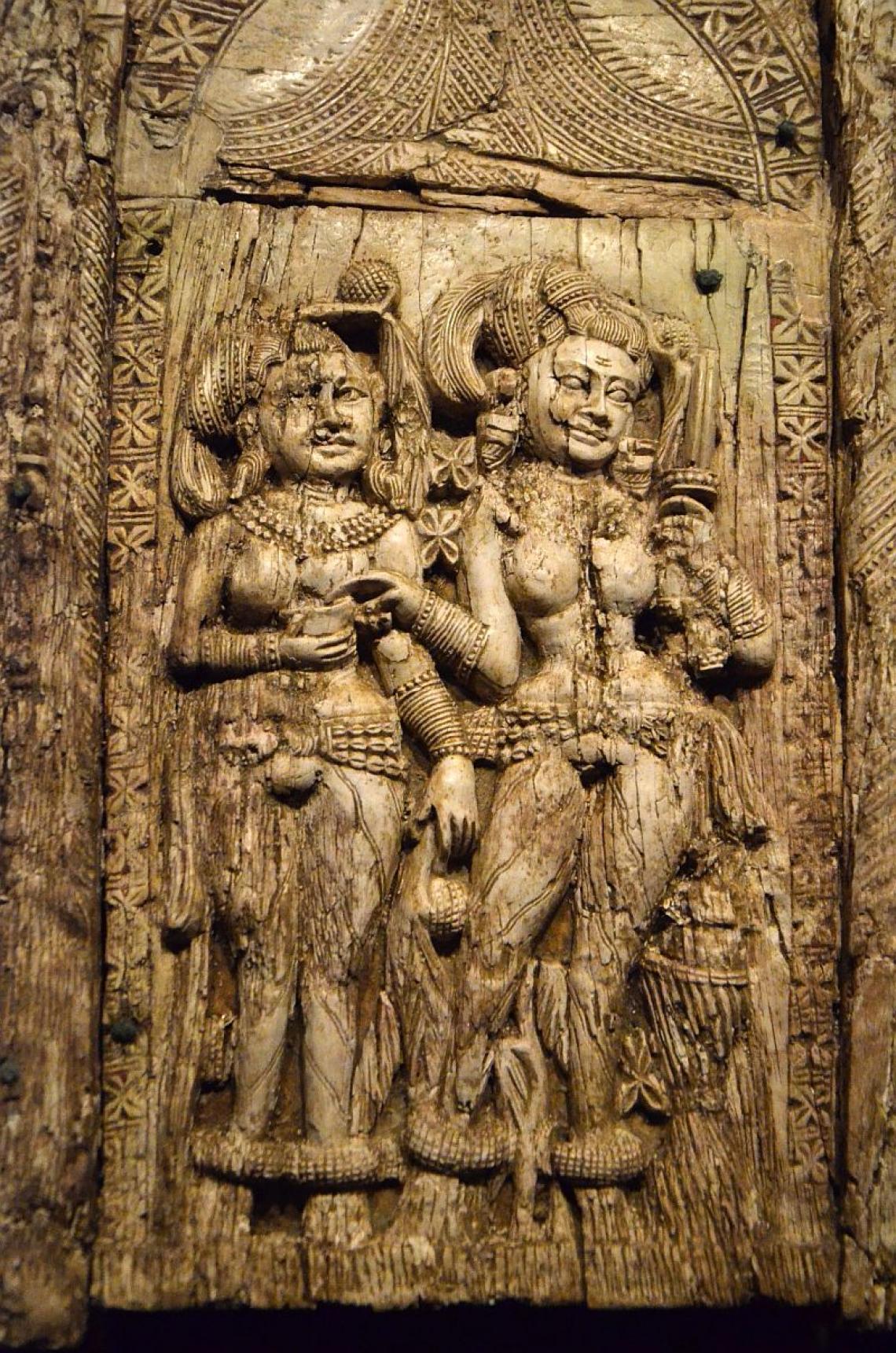

Ladies entertained by dancers, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, 1–200 CE, Ivory, 7.5 x 17 cm.

Discovered by Joseph and Ria Hackin between 1937 and 1939, the Begram ivories comprise the third largest group of objects excavated from the Begram hoard in present-day Afghanistan. This is a group of ancient artefacts known to have been exchanged along the Silk Road, and includes Roman and Chinese objects. Although there has been much debate about the date and place of their manufacture, contemporary scholarship dates these artefacts to the first or early second century CE, when the region was under Kushan rule. Most of the objects are small in size and were probably used to embellish wooden furniture, which had long perished from decay by the time the ivories were discovered. They are stylistically complex and, in their motifs and conventions, show resonances with several Indic traditions of the time, such as those of Sanchi, Mathura, Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda and Kanganhalli.

(Left to right) Ladies at Toilette, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, 50–200 CE, Ivory, 7.2 x 5.3 cm; Young Woman with a spear, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, 50–200 CE, Ivory, 9 x 4 x 1.7 cm.

Most of the ivory objects are small bands and plaques that are variously carved in low or high relief, as well as a small number of sculptures carved in the round. Their subjects are typically female figures depicted in toranas, arches or doorways, with male figures being relatively rare. The women are usually flanked by vegetal symbols of fertility and plenitude, as well as mythological and fantastical creatures, making them reminiscent of the yakshis or shalabhanjikas that often adorned the walls of ancient Indian temples and stupa complexes. At their least ornamented, the figures are shown wearing an antariya on the lower body, bracelets, necklaces and anklets. Some additionally wear multiple necklaces, earrings, headdresses, rows of bangles and low-slung girdles around their waists.

The freestanding sculptures often show a woman in the tribhanga pose standing on a makara, which acts as the base of the statuette. The necklaces, headdresses and hair ornaments, as well as the figures’ facial features, in these sculptures reveal the co-presence of Greco-Roman, Central Asian as well as Mediterranean stylistic conventions. Another noteworthy example of cultural confluence is a statue of a woman riding a gryphon, a creature generally not seen in later Indic iconography.

(Left to right) Standing woman, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, 50–200 CE, Ivory, 78 x 3.3 cm; Male bust, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, 50–320 CE, Ivory, 5.4 cm.

Some elements of the imagery offer insights into the lifestyle and daily habits of the time. In one notably elaborate example among the relief sculptures, a figure is shown holding a mirror in her left hand while rummaging with her right hand in a bowl being held by another woman beside her. Given the presence of the mirror, scholars have suggested that the bowl was likely meant to contain cosmetic materials. Above the figures two architraves are depicted, detailed with various mythological creatures from Indic traditions, including yakshas, yalis and kinnaras.

For most of the twentieth century, scholars believed that the Begram ivories were part of the royal treasury of the Kushan dynasty — accumulated between the first and third centuries CE and concealed in the rooms they were eventually discovered in, in order to protect them from the onslaught of the Persian Sasanian army in the mid-third century CE. However, recent archaeological evidence suggests that the ivories were among the vast range of commodities that were exchanged along the Silk Road, reaching Begram from various Indic cultural hubs through a combination of land and sea networks. The scholars belonging to this school of thought have generally based their findings on stylistic comparisons between the Begram ivories and the stone sculptures of the ancient Indian Buddhist monumental structures.

Decorative plaque from a chair or throne, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, Photographer: Merryjack, c. 100 CE, Ivory.

Scholar Sanjyot Mehendale suggests that the ivories were probably produced in local workshops by groups of itinerant ivory traders and craftspeople who were conversant with the many stylistic and iconographic conventions of ancient India. This argument is bolstered by the representational consistency of the Begram ivory plaques, almost all of which depict women framed by vegetal, mythological and architectural motifs and decorations. Mehendale also suggests that the comparisons between these portable ivory objects and the monumental stone arts of ancient India should be made with caution, as small, mobile objects like the ivories are able to reflect changing trends with relative immediacy, while stylistic diffusion occurs much more slowly in monumental works that are rooted in place.

Decorative plaque from a chair or throne, Kushan, Kushan, Begram, Afghanistan, Photographer: Merryjack, c. 100 CE, Ivory.

Since their excavation, most of the Begram ivory statuettes have been housed in the National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. However, during the years of unrest following the outbreak of civil war in the country in 1992, many of these objects were lost, stolen or irreparably damaged. Despite this, many of the ivories have been identified, acquired and restored to their original context through the efforts of private individuals as well as institutions, such as the British Museum. The latter, through its exhibition Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, also contributed to the scientific study of these objects. Aside from this, new publications such as Francine Tissot’s catalogue for the National Museum of Afghanistan, have aided scholarly analysis of Begram ivories through its inclusion of photographs as well as speculative illustrations of wooden furniture pieces within which these ivories were originally set. Thus, even though the debates around the antiquity and place of manufacture of the Begram ivory statuettes are far from settled, much useful scholarship has been added in recent years to the existing research, which enriches our understanding of these stylistically complex historical objects.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.