Hamid Bhakari Punished by Akbar (Folio from a Manuscript of the Akbarnama, Folio from the Davis Album), Manohar, India, c. 1604, Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 33.3 x 21 cm.

Jahangir Shoots Malik Ambar (detail from folio), Painted by Abuʾl Hasan, c. 1620. Gouache on paper, 25.8 × 16.5 cm.

Balanced on top of a globe, a regal figure shoots arrows at the head of a dark-skinned man, which is impaled on a lance. Cherubs hover over him in the brilliant blue sky, offering him more weapons to kill his enemy with, while a gun rests against the vertical lance. The delicate lettering of Persian verses scattered within the frame identifies the figures in this dramatic composition. They tell us that the archer is emperor Jahangir, of the Mughal dynasty that ruled northern India from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, and that the disembodied head belongs to Malik Ambar. Ambar was originally an African slave who established himself as an important military leader in India, becoming prime minister of the Ahmednagar Sultanate in the Deccan. Challenging and resisting Mughal power in many battles, Ambar had become Jahangir’s chief nemesis in the early 1600s. In reality, Jahangir was never able to overpower or vanquish him. Clearly, therefore, the painting does not present a historical account of events. Rather, it is the wishful depiction of an imagined victory, and an illustration of the cosmic worldview and grandeur that its patron—Jahangir himself—wished to present.

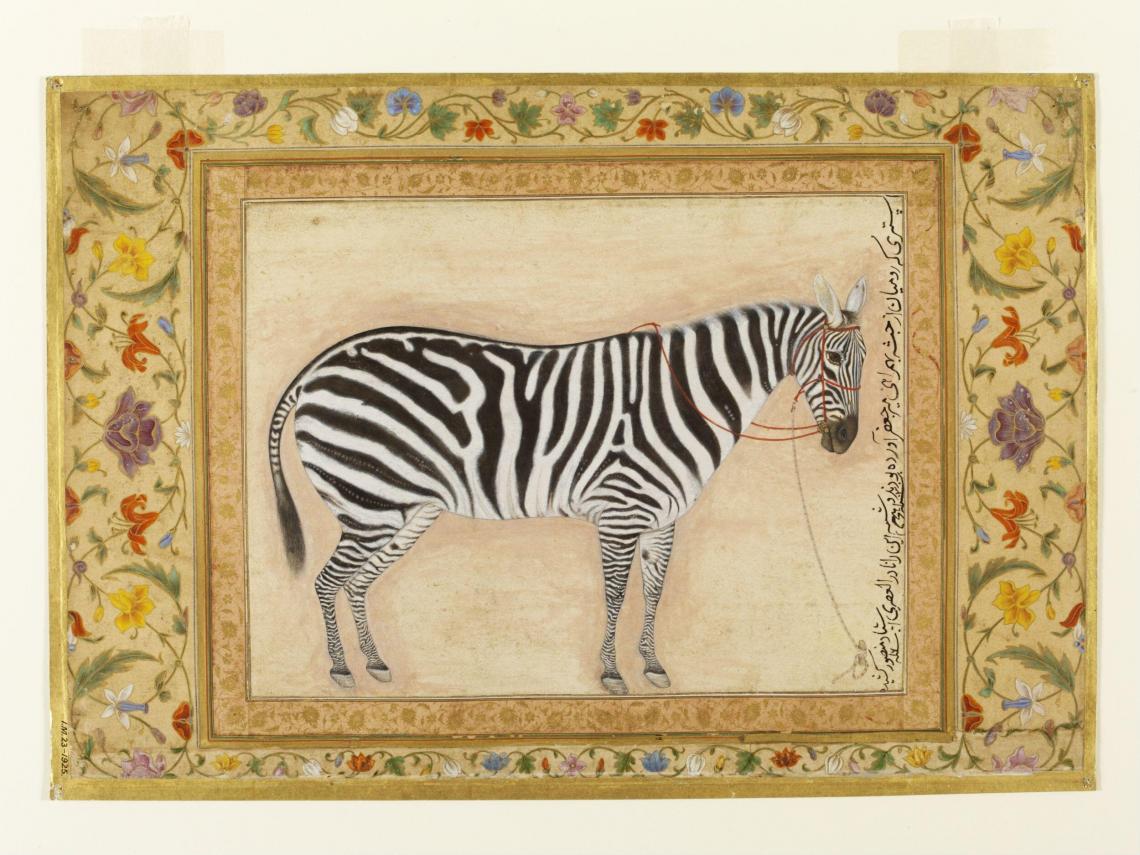

Zebra, Painted by Mansur, c. 1621. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 18.3 x 24 cm.

Another painting from Jahangir’s workshop of artists shows a detailed, realistic rendering of a zebra. Having received the animal as a gift, Jahangir was so fascinated by its unusual form that he inspected it thoroughly. Recording his thoughts in his memoir (the Jahangirnama), he wrote: “the painter of destiny had produced a tour de force on the canvas of time with his wonder-working brush.” Ever interested in nature’s curiosities, he immediately ordered Mansur, one of his favourite painters, to paint the animal in all its glorious detail—and the result is a work that elevates precise scientific documentation to the status of sublime art.

Both these paintings, disparate as they are, represent the apogee of Mughal manuscript painting—a major tradition of miniature painting in the history of South Asia and the wider Islamic world. It emerged in the mid-sixteenth century in the royal ateliers (workshops) of the Mughal kings, and remained highly influential until the late eighteenth century. Known for their intricacy, luminosity, pluralism and naturalism—in both style and subject matter—these Mughal miniatures embodied a vast range of influences and expressions. Stylistically, they synthesized influences from the Persian tradition and various regional, pre-Mughal manuscript painting traditions, as well as European Renaissance images. In terms of subject matter, these paintings served as historical documentation; visual aids for storytellers; illustrations for literary texts, recipe books, scriptures (despite the doctrinal ban against image-making in Islam) and scientific documents; and even as ritual objects.

How did a South Asian painting tradition of such range, scale and sophistication develop under the patronage of these perennially warring, post-nomadic descendants of Central Asian conquerors?

Books and paintings: The education of a Mughal prince

The Mughals had as their ancestors two great military figures—Turkic conqueror Timur Lang and Mongol ruler Genghis Khan. Conquering vast swathes of land, both left behind a particular legacy of political expansionism as well as cultural refinement. Thus, Timur’s sons and grandsons, among whom the Mughals were a minor branch from the Ferghana Valley, were not only great conquerors but also scholars and great connoisseurs of art.

Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, was in the midst of war nearly throughout his life. Yet he managed to write the Diwan-i-Babur—a collection of poems, and the Baburnama—a memoir; as well as practice calligraphy and invent his own script known as the Khatt-i-Baburi, commission gardens and mosques, and collect fine books and manuscripts. The love of fine books, in particular, was shared by Babur’s son Humayan, who lived a similarly itinerant life: buffeted by fate, Humayan was a king without a kingdom—but not without a library, or more precisely, a kitabkhana. Stories abound of Humayan finding himself unable to stay away from his books, carrying them even to encampments and battles, where an entire tent would be dedicated to his library. Despite this, he was struck by the aesthetic sophistication he encountered in his visit to the Persian court of Shah Tahmasp in Safavid Persia (present-day Iran), where he hoped to negotiate for military aid. As part of his negotiations, he also brought back two Persian master artists—Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd us Samad—who would go on to establish his imperial painting atelier once Humayun regained his territories in India.

Thus, by the time Humayun’s son and successor Akbar was born, a keen interest in books, manuscripts, and paintings was integral to the education as well as identity of a Mughal prince.

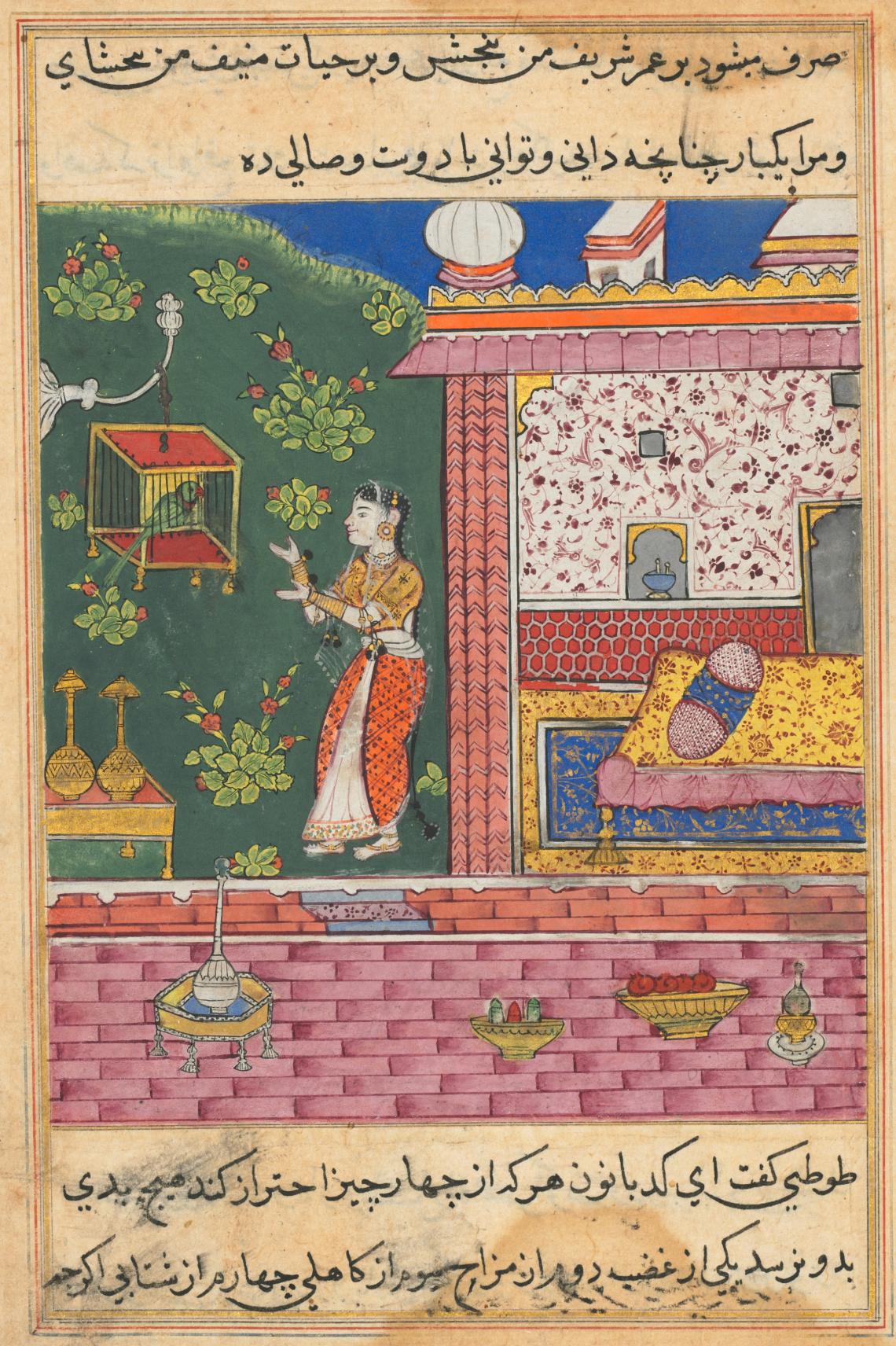

The Parrot Addresses Khujasta at the Beginning of the Thirtieth Night, page from Tutinama, Mughal India, court of Akbar (reigned 1556–1605), c. 1560. Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper; overall: 20.3 x 14 cm; painting only: 11.5 x 10.2 cm.

Expansion and excellence: The atelier under Akbar

Akbar expanded the infrastructure for book-making and painting, and his royal atelier grew from about thirty artists in 1557 to over a hundred in the 1590s, consisting of painters, colourists, calligraphers, bookbinders and other specialists. In order to efficiently carry out a large number of projects—including illustrated manuscripts, individual paintings and designs for other objects—the hierarchy within the atelier remained somewhat fluid and highly collaborative. Within a given folio, a master painter composed the image based on the text, to be coloured in by a junior artist. The expanding atelier hired artists from far and wide: aside from local and Persian painters, artists were brought in from western India, Kashmir and Lahore, as well as other parts of South Asia. These artists brought their own artistic traditions with them, which would not only shape the visual language that was to develop in the Mughal painting studio, but are also evident in the diversity of style within the early manuscripts—in the Tutinama (“Tales of a Parrot”), for instance. One of the earliest illustrated manuscripts commissioned by Akbar, the manuscript from the 1560s narrates the stories told by Maymun’s pet parrot to his wife Khujasta during the fifty-two nights he is away. In every illustration of Khujasta and the parrot, the influence of a different style, idiom and painting tradition can be seen—from the shape of the parrot’s cage, placement of figures, colour palette, embellishment of textiles and other ornamental details, to the elegance of style and painterly ability. So far, the disparate styles of the atelier’s artists had not yet melded into a distinctive ‘Mughal’ style of miniature painting.

It was the Hamzanama (“Book of Hamza,” a fictional biography of the prophet Mohammed’s uncle Hamza), made under Akbar’s reign, that became the laboratory where the Mughal style was negotiated. The project is remarkable for its scale and style. The Hamzanama consisted of 1400 large paintings, each approximately 69 x 54 cm, which would have been held up as story-telling aids in a popular performance tradition. Through the successive folios of the Hamzanama, it is possible to track the arc of the developing Mughal style, starting at one point and ending at another point entirely: combining aspects not only of Persian and Indian artistic traditions but also of Renaissance art, which was causing great artistic ferment with its striking arrival in the atelier. Renaissance images, especially Biblical ones, arrived at the Mughal courts as prints with visiting merchants and missionaries. These quickly became valuable assets for the Mughal artist, who not only copied their style and subjects, but also interpreted them anew and applied his learning to everything that he worked on in the Mughal context.

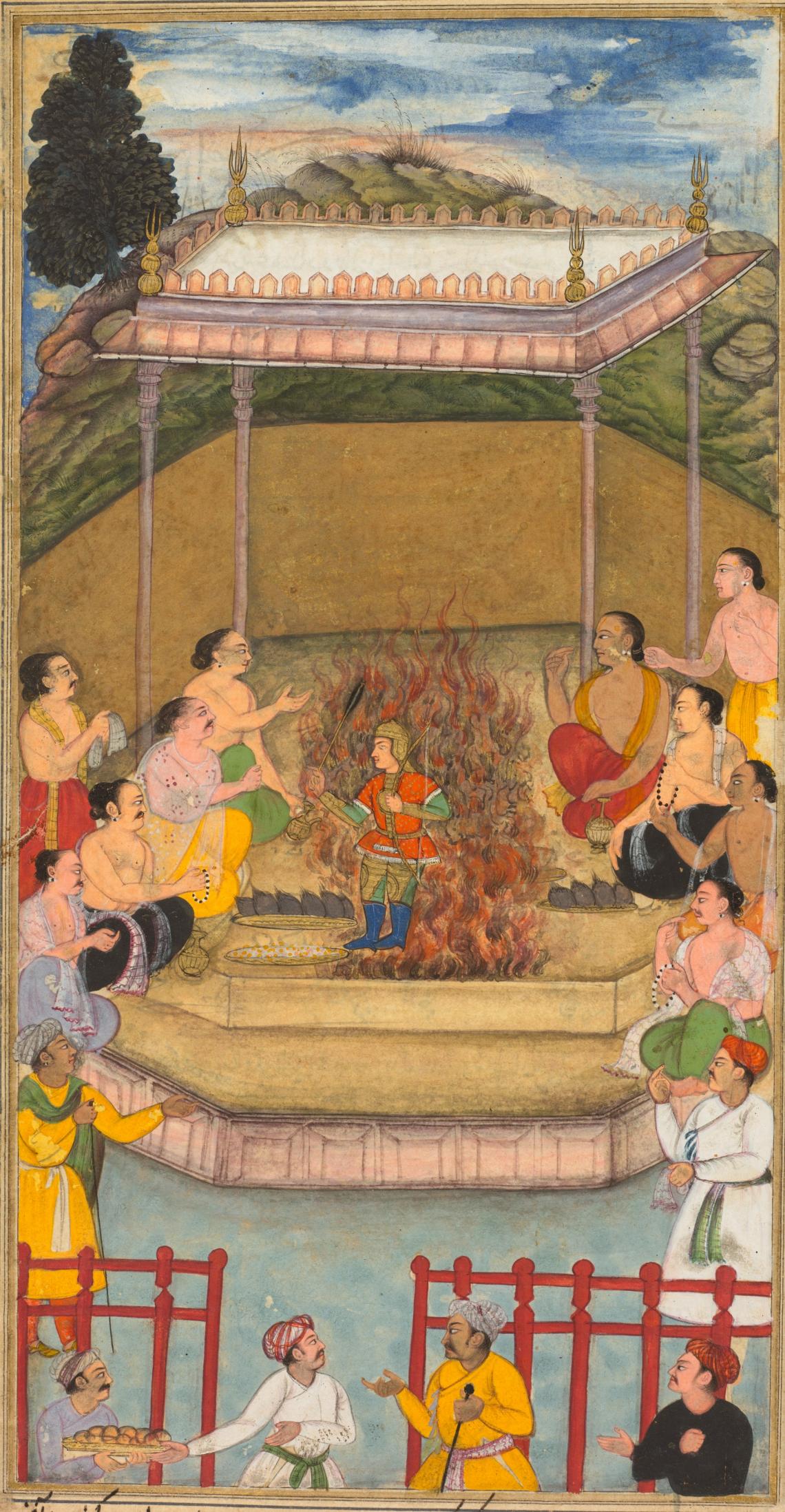

Yaja and Upayaja Perform a Sacrifice for the Emergence of Dhrishtadyumna from the Fire, from Adi-parva (volume one) of the Razmnama, 1598, Attributed to Bilal Habshi (probably Ethiopian, active late 1500s). Opaque watercolor with gold on paper; 29.8 x 16.8 cm.

The influence of Renaissance art and Christian allegorical imagery can be seen even in manuscripts that deal with Hindu themes and texts—especially the great Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Akbar set up a translation bureau—or maktab khana—in 1574, to translate the major Indian texts from Sanskrit into Persian. An abridged translation of the Mahabharata was prioritized as it was seen as the most comprehensive epic of Indian culture, offering a relatively secular reading for both Hindus and Muslims. This illustrated version of the Mahabharata came to be known as the Razmnama, or Book of War. Akbar ordered all his noblemen to read and commission personal copies of these translations, so that they might understand the people of a different culture and build bridges between the diverse communities of India. These were difficult projects. Given that these were the first illustrated manuscripts of the Sanskrit epics, the Mughal artists had no visual precedents to guide them, which made the illustration of these books all the more exciting and important.

Other important illustrated manuscripts that were commissioned under Akbar’s reign include the Akbarnama (“Book of Akbar”), a real-time documentation of Akbar’s reign with collaboratively produced illustrations, and the Khamsa of Nizami (five poems of Nizami Ganjavi c. fourteenth century).

The story of Mughal painting in South Asia, however, had only just begun. The next major impetus came under the reign of Jahangir, the son and successor of Akbar, bringing significant changes at every level: from the composition of the imperial atelier to the style, subject matter and use of the painted image in the Mughal world.

Observation and allegory: Jahangir’s celestial vision

During Jahangir’s reign, the focus moved away from manuscripts to muraqqas (albums), and the emphasis shifted from quantity to quality. The number of artists retained by the imperial atelier for long-term projects was significantly reduced: scholars suggest that there were only about thirty artists in Jahangir’s atelier—each one a master, who worked individually on paintings. The idea of the artist as an author, an individual whose work is distinct from that of another artist, became important in this period.

Two major developments concerning subjects and style took place under Jahangir’s patronage. First, the emperor’s deep interest in the natural world led him to have his best artists produce works with animals and plants as their subject matter. As we see in Zebra, these works were naturalistic depictions of scientific precision. Second, particular emphasis was placed on realistic, accurate portraiture. This came from a deep-rooted belief in physiognomy, or the science of firasa, which regarded outward facial features and expressions as indicative of a person’s inner qualities and character. Jahangir had portraits painted—in profile or three-quarter profile—of himself, his sons, courtiers and even of his enemies so that he might have a better understanding of their psychology. Nanha’s painting of Shah Jahan inspecting jewels with his young son also demonstrates both of these concerns. In the central image, father and son are depicted in their royal pastime, with the future emperor Shah Jahan meditating on the qualities of a ruby, as the young Dara Shikoh holds a turban ornament. The emphasis on the likeness of facial features, the attempt to accurately capture the volume of the bodies and the inventive use of chiaroscuro and sfumato comprise a representational realism that was unprecedented in both Iranian and earlier South Asian works. The duo is framed by a wide border exquisitely illuminated with figures of birds, including peacocks, chukar partridges and demoiselle cranes, among a variety of flowering plants—all painted in spectacular naturalistic detail.

Jahangir was interested in works that combined such close observation with layers of subtle and sophisticated symbolism. His allegorical portraits or ‘dream’ paintings are the best examples of this combination of the real with the fantastical and metaphorical in a seamless continuum.

Jahangir Shoots Malik Ambar, for example, combines the fantasized killing of the Deccan chieftain with the allusion to an actual event mentioned in Jahangir’s memoir, the Jahangirnama. A memoir entry from 1617 narrates that on the evening before Jahangir’s son Prince Khurram was to face Malik Ambar’s army in battle, an owl had perched itself on the palace roof around dusk. As the bird was commonly considered to be a harbinger of death, the emperor felt impelled to take immediate action. A marksman par excellence, he shot and killed the bird himself with his musket just as darkness was setting in. The painting depicts this fallen owl dangling above the gun that brought it down. To its right, a pair of perfectly balanced scales hangs on Jahangir’s famous ‘chain of justice’, shown running between the globe and the lance, signifying the emperor’s professed aspiration for fairness. But these are the painting’s only anchors to material reality—the other motifs, while meticulously rendered, are symbols from another, more spiritual, reality. Here, the emperor embodies an all-powerful, almost supernatural being. Illustrating Islamic cosmology, the world upon which he stands rests on the cosmic bull Kujata, who in turn is carried by the giant fish Bahamut. The mythical huma bird looks after his legacy, and angels assist him in redirecting the curse of the inauspicious owl towards his enemy. Thus, a living owl is pictured atop the head of Malik Ambar as a talismanic curse.

Decline and legacy of the Mughal atelier

The atelier and its artists that had flourished under the patronage of Akbar and Jahangir were only modestly functional in comparison during the reigns of Jahangir’s successors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. While Shah Jahan maintained and funded the atelier, his interest and resources were mainly directed towards architecture. Becoming primarily a medium of courtly representation, the paintings of this period had a stiff formality and lacked the experimentation and aesthetic flair they showed under the previous emperors. Nonetheless, the muraqqas and illustrations in texts like the Padshahnama from this period were highly naturalistic and technically accomplished.

Aurangzeb’s religious orthodoxy led him to move funding away from the atelier a few years into his reign, but for most of the 1660s the emperor tolerated painting as a courtly art. Several highly valued examples of portraits and court scenes in the Mughal style were produced in this period.

With the exception of a revival under the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719–48), Mughal patronage for miniature painting dwindled significantly in the eighteenth century. Thus, artists were forced to seek employment outside the imperial court, which resulted in Mughal characteristics prominently making their way into the painting traditions of other regional kingdoms, particularly those of the Rajput and Maratha courts. These included the careful use of light and shadow to add volume to the figures, the naturalistic depiction of folds in clothing and the realistic rendering of faces. Under British rule in the Indian subcontinent, the tradition of Mughal miniature painting, with its emphasis on naturalism, was incorporated into the Company School.

Today, dispersed folios, and more rarely whole manuscripts, in the Mughal style are housed at various museums as well as private collections across the world. Whether beheld in parts or as a whole, Mughal miniatures continue to captivate viewers centuries after their subjects, authors and patrons have passed. This is thanks to their singular visual language, which combined intellectual erudition with extraordinary levels of artistic sophistication to create objects of everlasting beauty.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.