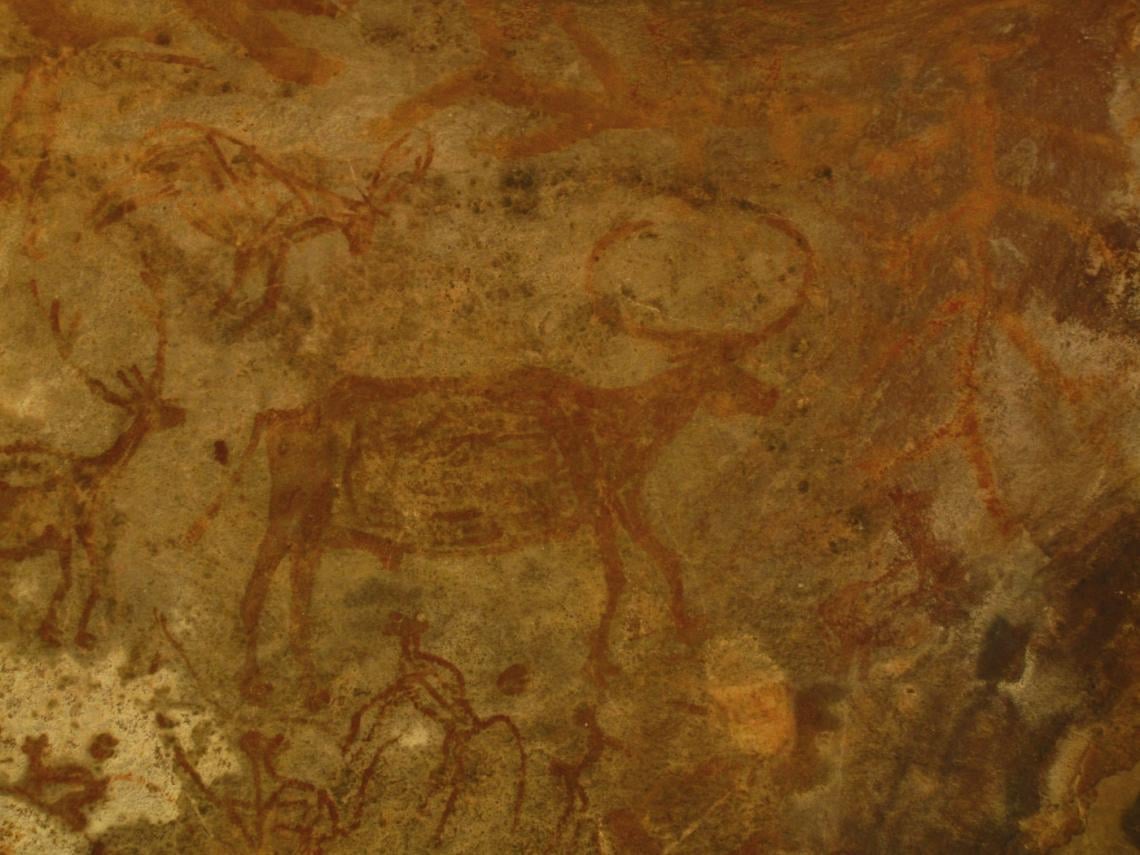

Paintings in Rock Shelter 8, Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, Bernard Gagnon, c. 2013.

Widely acknowledged to be the earliest evidence of art in South Asia, the Bhimbetka cave paintings are Prehistoric paintings found on the Bhimbetka rock shelters in the Raisen district of present-day Madhya Pradesh. Bhimbetka comprises over 750 rock shelters, of which over a hundred have paintings depicting animal and human figures in shades of green, red, white, brown and black. The earliest of these illustrate scenes from the lives of hunter-gatherers of the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods — a time when many animals were yet to be domesticated, humans were nomadic and collective civilisations were not yet in existence.

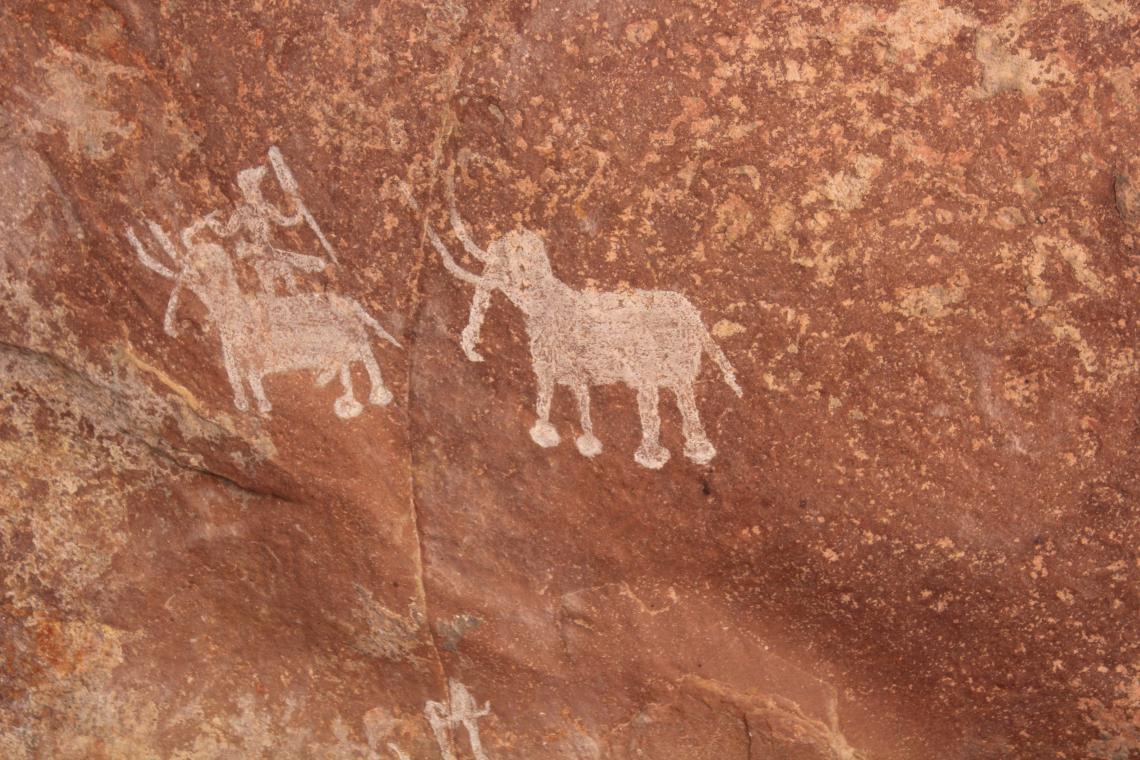

Two Elephants with a Man Standing on One Elephant's Back, Cave 3, Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, Arian Zwegers, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh India, c. 2012.

Evidence suggests that the most densely painted caves allowed in more sunlight and were typically uninhabited. This also supports the widely accepted belief that these paintings were not meant to beautify or decorate humans’ living spaces. The fact that many of these cave paintings overlap — implying that the rocks were painted on repeatedly and across successive historical time periods — has allowed archaeologists to assess their historicity. The Bhimbetka paintings have been classified into nine phases under three broad cultural periods: Phases I–V in the Mesolithic period, Phase VI in the Chalcolithic period and Phases VII–IX in the Historic period. Some scholars further suggest that the paintings could even have originated around 40,000 BCE or earlier. Based on considerable archaeological evidence, it is suggested that there is a clear distinction between the cave paintings from the Mesolithic and Historic periods and those from the Upper Palaeolithic period and later Mediaeval period, which are fewer and less significant in terms of a distinct style.

Early Bhimbetka paintings predominantly feature wild animals such as gaur, a native variety of wild ox, deer such as the chital, monkeys, wild boars, stags and elephants as well as hunting scenes in which humans are depicted with bows and arrows and headgear. There are also depictions of different types of scenes, including ritual practises, women digging out rats from holes and men and women foraging for fruits and honey. Contemporary scholars have categorised the painted animal figures in these illustrations into natural, geometric or abstract styles based on whether they are simple outlines, partially filled-in or silhouetted figures. For instance, several pregnant animals painted with visible markers such as enlarged stomachs are outlined and drawn using naturalistic or geometric styles. Sometimes, instead of being coloured, the body of an animal is filled-in with another animal, suggesting a more conceptual style. For instance, some paintings depict an elephant painted within the outline of a deer, which could suggest a fantastical and possibly humorous approach to depicting subjects.

Cave Paintings, Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, Vijay Tiwari, c. 2016.

In contrast, later paintings from the Historic period onwards depict processions, scenes of warriors with swords, shields and daggers and collective rituals. These paintings are characterised by a marked absence of animal figures, which are disproportionately drawn whenever they do appear. It has also been suggested that the motifs used in some of these later paintings reveal the religious influence of Hinduism or Buddhism. In some, there are clear depictions of gods such as Ganesha and Shiva, representations of the Mother Goddess and symbols such as the trishul and swastika. Archaeologists have been able to differentiate these paintings from the earlier, more faded paintings underneath through processes such as radiocarbon dating and other methods. By this time, humans were no longer living in caves as hunter-gatherers but were in the early stages of civilisation and a sedentary life with domesticated animals.

To produce these paintings — especially the earlier iterations — brushes were most likely made from twigs that were chewed to soften and discard the fibres. Additionally, fingers, bird feathers and animal hair are believed to have been used as brushes. Pigments for different colours may have been obtained from vegetables or from surrounding sedimentary rocks. Hydrated iron oxides from rocks were likely used to make shades of ochre and red and burnt to produce colours such as yellow, rust orange and brown. Bird droppings or plant sap may have been used for whites. Evidence suggests that colours were only used in the wet form — by mixing pigments with oils and water — and never in solid or powdered form.

Painted Wall, Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, c. 2016.

Scholars believe that the Bhimbetka cave paintings were quite mature and advanced for their time and were probably not the first works of art created by human beings in the region. Although the purposes of these paintings are unknown, they provide immense historical information about humans, their relationship with animals and nature, the stages of Prehistoric hunter-gathering and the eventual transition into more sedentary civilisations with domesticated animals.

The Bhimbetka rock shelters were marked as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and a Blog, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.