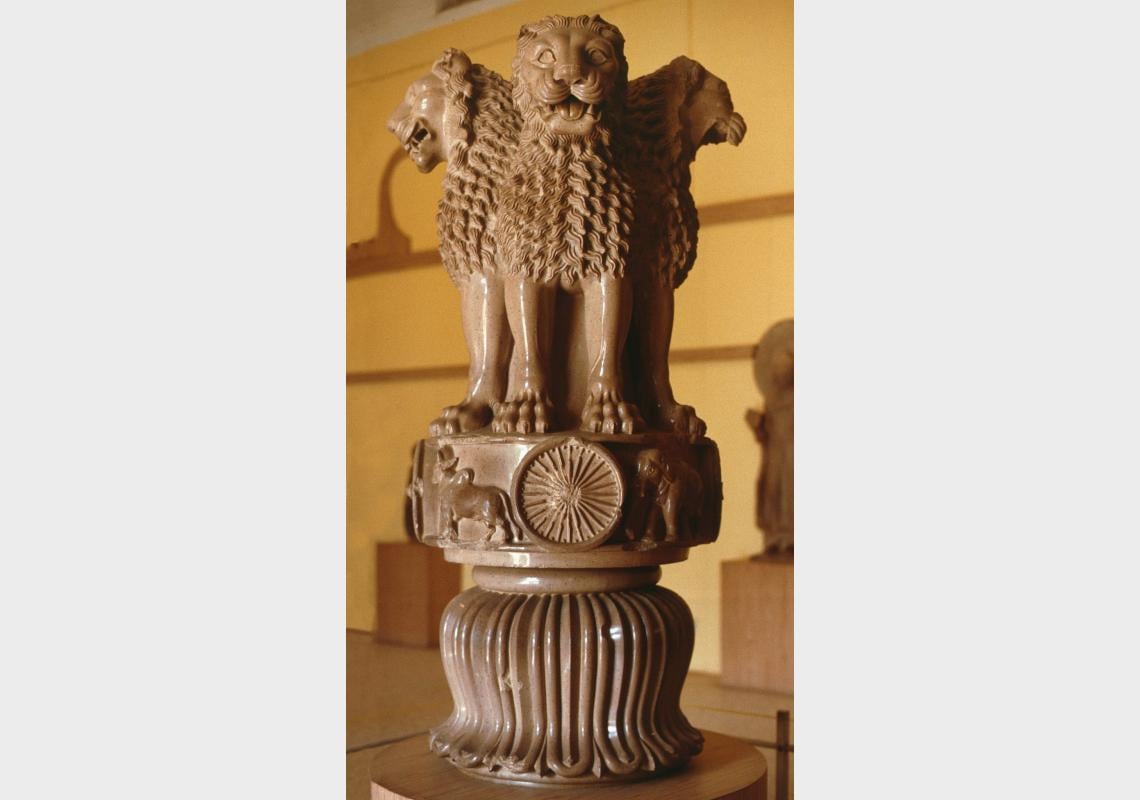

Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka, Mauryan Period, Sarnath, c. 250 BCE, Chunar Stone.

One of the earliest stone sculptures made under the patronage of the Mauryan king Ashoka, the lion capital at Sarnath, Bihar, depicts four male Asiatic lions seated on a round abacus with their backs to each other. The capital is carved from a single block of highly polished Chunar stone that is separate from the block used for the pillar shaft, which features the inscribed edicts of Ashoka. The most elaborately carved of all surviving Ashokan capitals, the lion capital stands at a height of two meters and is dated to ca. 250 BCE. The broken remnants of the pillar, as well as the complete, but detached, capital were formally excavated around the year 1905 by F O Oertel. The capital is believed to have originally been attached on top of the pillar. Also among the findings were fragments of a large dharmachakra stone with thirty-two spokes, which is presumed to have rested on the capital in a likely reference to the Buddha’s first sermon.

The four lions comprising the capital are depicted with their mouths open as if mid-roar and their manes are arranged in neat ringlets. They also portray an understated but carefully studied musculature. Scholars claim that the eye sockets of the lions were once fitted with semi-precious stones. The overall form of the lions is poised, heavily stylised and compact, similar to the lion images carved in Achaemenid Persia, which is a known source of influence for Mauryan architecture. In addition, the abacus features four animals — an elephant, a lion, a bull and a horse, carved in high relief and suggesting that the sculptor(s) may have been familiar with the anatomies of the animals. They appear to be moving in a clockwise direction and are separated by four chakras with twenty-four spokes each. The abacus rests on an upturned, bell-shaped lotus with elongated, fluted petals, which are also believed to have been borrowed from the Achaemenid style of architecture.

Sarnath is the site of the Buddha’s first sermon and the lion capital is believed to have been built to commemorate the occasion. Therefore, the various icons that appear on the capital are recurring symbols within Buddhism. The dharmachakra is a solar symbol with its origin in many faiths and, therefore, has multiple interpretations. Here, it is believed to represent the Buddha “turning the wheel of the law” with his first sermon at Sarnath. It also possibly refers to Ashoka’s title of Chakravartin, meaning “a ruler whose chariot wheels roll everywhere.”

Some sources interpret the lions as personifying the Shakyamuni (of the Shakya, or lion, clan) Buddha who preached his sermons at Sarnath. Their open mouths are interpreted as spreading the Buddha’s teachings, the Four Noble Truths, far and wide. An almost identical lion capital with its mouth open is found at the Sanchi pillar, which is another site where the Buddha is believed to have delivered sermons. Some interpretations suggest that the lions symbolise not only Buddha, but also Ashoka. As a significant ruler of the first historical empire in India with a vast geographical reach, strong relations with foreign states and diverse secular cultures, Ashoka was held in parallel with the Buddha, having limitedly imbibed the Buddhist way of life.

Ashokan Capital Stamp, Issued by the Government of India, c. 1947.

The animals on the abacus are interpreted differently by various scholars. According to Alfred Charles Auguste Foucher, and later accepted by most other scholars, the four animals are associated with the four milestone events in the Buddha’s life: the elephant, representing his mother Queen Maya’s dream of a white elephant entering her womb; the bull, representing his birth under the astrological sign Vrishabha; the horse, representing Kantaka, the horse on which Buddha fled his palace to pursue asceticism; and the lion, representing the enlightened Buddha and often known as Shakyasimha. The animals are depicted running in the clockwise direction and separated by four dharma chakras, possibly signifying the intention of setting the wheel in motion through the cycle of life or representing the Buddha setting the wheel in motion at the sermon at Sarnath. Another prevalent opinion is that these animals face the cardinal directions. They have also been identified as the four perils of samsara — birth, disease, death and decay — following each other in an endless cycle. The upturned lotus that the capital rests on represents purity in Buddhist art, sculpture, ritual and theory and symbolises rising above the mundanity of life to attain enlightenment.

In 1950, three years after Indian independence, the lion capital at Sarnath was adopted as the emblem of the Republic of India, with the lions representing virtues such as pride, power, courage and confidence. The inverted lotus bell has been omitted, and the motto ‘Satyameva Jayate, meaning “truth alone triumphs,” is inscribed in Devanagari script below the abacus. The original lion capital is now preserved at the Sarnath Museum, near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and a Blog, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.