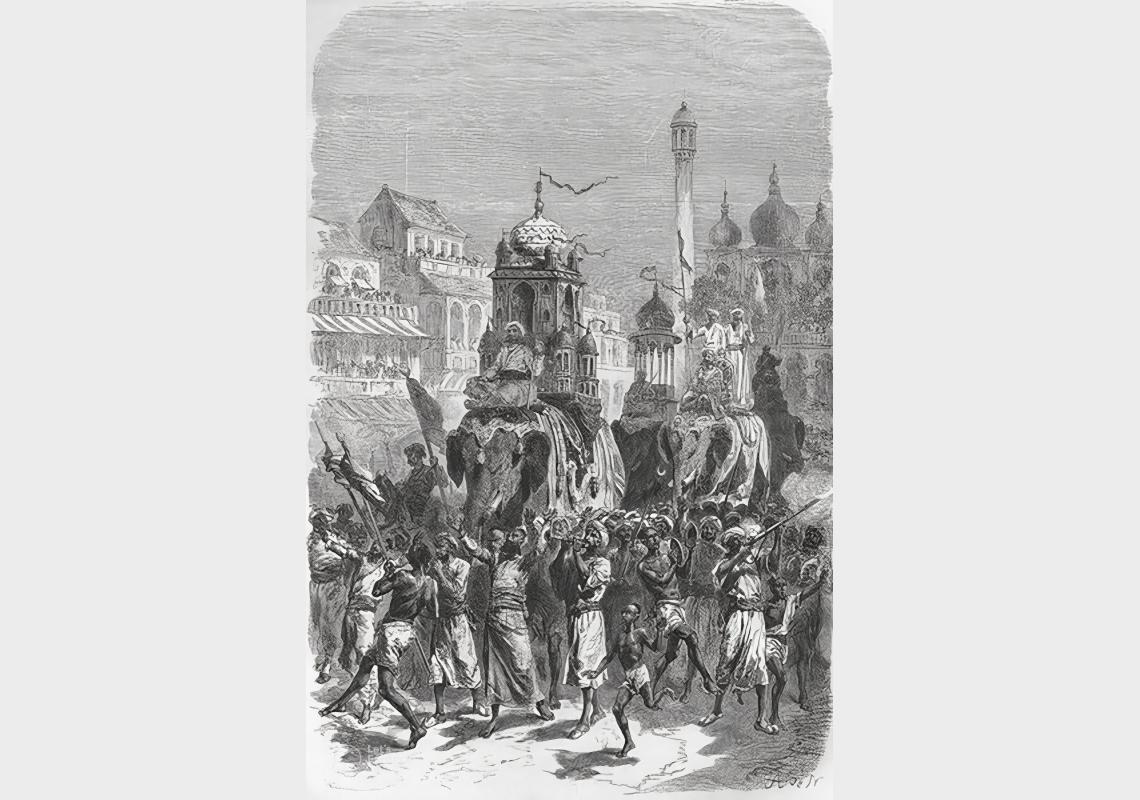

The Moharum at Bhopal: Process of the Tazeeas, Louis Rousselet, C.1878

Interpretations of the tomb of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Moḥammad, tazia (also ta’zia, taziya, tabt or taboot) is a shrine constructed to be a part of the procession on the day of Ashura. The day of Ashura is the tenth day in the month of Muharram when Imam Hussain is believed to have died in battle at Karbala in 680 CE, and is considered to be a significant narrative on martyrdom and sacrifice for Shia Muslims. It is believed that tazia arrived in India in the fourteenth century because of the Mongol ruler, Taimur, who paraded a replica of Hussain’s Karbala tomb around his military camp as a way of mourning. Some accounts also suggest that the popularity of the practice of tazias was brought about by the Mughals, who encouraged it as a way for members of the royal family, who weren’t able to visit the shrines in person, to see the shrine.

Tazias form a part of the mourning ritual called azadari that takes place during the month of Muharram. The tazias are brought to be a part of both temporary individual azakhanas (a place for mourning during Muharram) as well as permanent structures within imambaras. The ritual of bringing tazia home followed by its dismantling is called taziyadari, though that is a term more popularly used within the Sunni tradition. Palm-sized tazias, known as mannati (prayer) tazia, made of cigarette boxes and coloured paper, are brought in along with a larger taziya and zarih – an elevated structure that surrounds a grave – for prayers during Muharram. The key differences between the two are that the zarih is a structure with a square base and round domes – unlike the tazia’s rectangular base and conical domes – and is a permanent structure within the imambara.

Khambat Muharram, Rauf Shaikh, c. 2009.

The tazias are commonly made of bamboo, coloured paper, transparent paper, papier mache and tinsel. The finished structures can vary in size from being several feet in height to palm-sized, but in most cases these are temporary and are created anew every year. Irrespective of its scale, the main components of the tazia include a takhat, or a rectangular base on which the structure is built; the dar or the main structure consisting of storeys and arches; the chhatri, or the canopy; and finally jhallar, or trimmings. At times the designs are often inspired by the aari-zardozi, a form of chain-stitching in Lucknow. While the popular colours used in tazias are red, associated with Imam Hussain, and green, associated with Imam Hasan, there is a vast variation in how these structures are designed in different parts of the country. Some variations include a jau ka tazia, made from barley (jau) and wood in Lucknow or a tazia made of mustard seeds near Jaipur. Some variations also include structural innovations, such as the use of the pattha (dorsal vein of a buffalo) as a sturdier alternative to thread to hold the bamboo together.

Muharram, Ramesh Lalwani, c. 2013.

As the tradition of tazia-making spread, a special group of artisans known as aaraishwale (decorators) emerged in the nineteenth century Lucknow who were in demand during Muharram to decorate the tazias. In some cases, families of artisans became responsible for the popularity of particular kinds of tazia, like the Mirza family of Lucknow that introduced the kamrakhi gumzi (starfruit shaped dome) tazia. Tazias have also been mediums of creative interpretations and continue to be so even today when there is easier access to the images of the actual tomb. Scholars conjecture that it could be due to the belief that this act of artistic creation is also a form of paying respects to the martyred Hussain.

Tazia-making is mostly observed in South Asia, regions with South Asian diaspora and parts of Fiji, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname and Jamaica. In Iran, tazia refers to a passion play or performance held during the month of Muharram depicting Imam Hussain’s death. Tazia is known as the tadjik in the Caribbean and tabuik in regions of Western Sumatra, Indonesia.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and a Blog, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.