Members of the CityU research team, (front row from left) Dr Zhang Liang, Dr Yan Jian, Dr Chan Kui-ming, (back row from left) Fan Ligang, Yi Wenkai, Zhu Xiaoxuan, and Li Jingyu. (Photo source: City University of Hong Kong)

The research was co-led by Dr Yan Jian, Dr Zhang Liang, and Dr Chan Kui-ming who are all from the Department of Biomedical Sciences (BMS) at CityU, in collaboration with scientists mainly from Northwest University in Xi’an. Their findings were published in the scientific journal Nature Methods, titled “CRISPR-assisted detection of RNA–protein interactions in living cells”.

Binding proteins determine RNA functions

The central dogma of molecular biology suggests that DNA is transcribed to RNA and RNA is translated into protein. But actually, only about 2% of RNAs code for protein. The rest 98%, named as non-coding RNAs (ncRNA) have been regarded as “dark matter” in cells for their yet mysterious functions.

In recent years, scientists have put many efforts into unveiling their actual functions, especially the long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA, meaning ncRNA with more than 200 nucleotides in length). LncRNA has become widely accepted as important cellular components participating in the regulation of gene expression. “LncRNA is the most interesting RNA species”, described Dr Yan. It is also the reason why the team has chosen lncRNA as the research subject.

Although lncRNA will not produce protein, they will bind with proteins and the interaction will determine their functions. Therefore, the identification of the binding proteins is crucial in understanding the lncRNA functions. However, current methods demonstrate quite some limitations, for example generating false positive signals, and cannot be done in living cells.

Two steps of CARPID: navigation and biotin-labelling

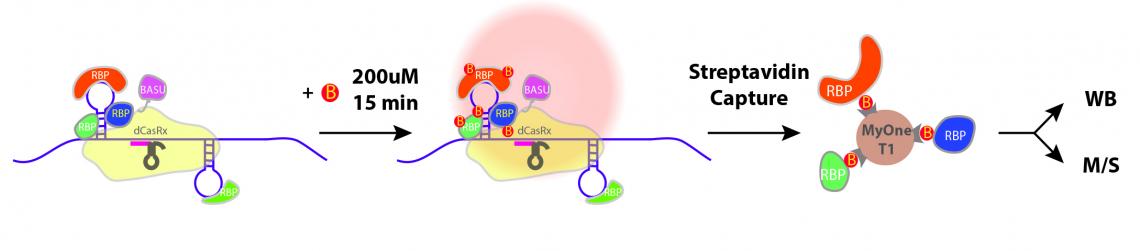

To overcome the limitations of the existing method, the research team came up with a novel method that jointly leverages the existing state-of-the-art gene-editing technology CRISPR/dCasRx system for RNA targeting, and the proximity biotin-labelling technology to identify the protein-protein interactions in living cells.

The team named the novel method CARPID, short for CRISPR-Assisted RNA-Protein Interaction Detection. “CARPID can sensitively detect binding proteins of RNAs in any lengths or concentrations whereas most other existing methods can only be applied to relatively long non-coding RNAs,” said Dr Yan.

The method is composed of two parts: navigation and proximity biotin-labelling. First, the team employed the CRISPR/dCasRx system to navigate so that the CARPID components including “a labelling tool” called BASU can be near the targeted RNA. BASU is an engineered biotin ligase, a kind of enzyme that would add biotin (a kind of vitamin with strong binding) to proteins that bind with that targeted RNA. In this way, those proteins which are near the targeted RNA would be labelled.

After the “labelling”, the team used a biotin-binding protein called streptavidin to identify those proteins labelled by BASU. In this way, the binding proteins were revealed easily.

The yellow shade depicts the navigation system (CRISPR) that directs the CARPID components including BASU to the targeted RNA (a purple rope with stem-loops on the left side). BASU “labels” (B) the adjacent binding proteins (RBP). Streptavidin (MyOne T1) is then used to recognize the binding proteins. (Photo source: DOI number: 10.1038/s41592-020-0866-0)

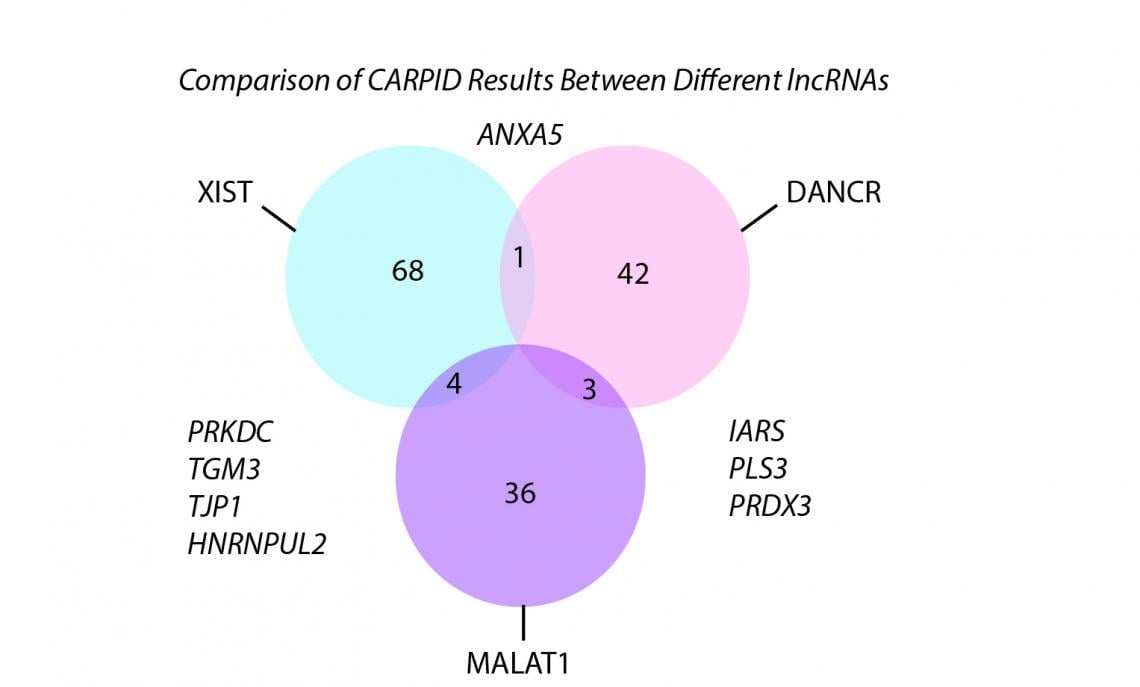

CARPID is applied to three different lncRNAs. The result shows that there was not much overlapping of binding proteins, which demonstrated the high specificity of CARPID. (Photo source: DOI number: 10.1038/s41592-020-0866-0)

High specificity and applicability for lncRNAs of different lengths

To test the specificity of CARPID, the team applied it on three different lncRNAs, namely DANCR, XIST, and MALAT1. Experiment results showed that there was not much overlapping of binding proteins. This demonstrated the high specificity and applicability of the CARPID method for lncRNAs of different lengths and expression levels.

“This high level of specificity is achieved because the navigation by CRISPR is very precise. We can even obtain the information of exactly which section of the RNA that protein binding occurred,” explained Dr Yan.

Also, CARPID would not affect the physiological condition of the targeted cell, and the cell is still alive with normal gene expression landscape after the whole process. “With this new method, we can obtain dynamic results if we check the same RNA target at different times,” added Dr Zhang.

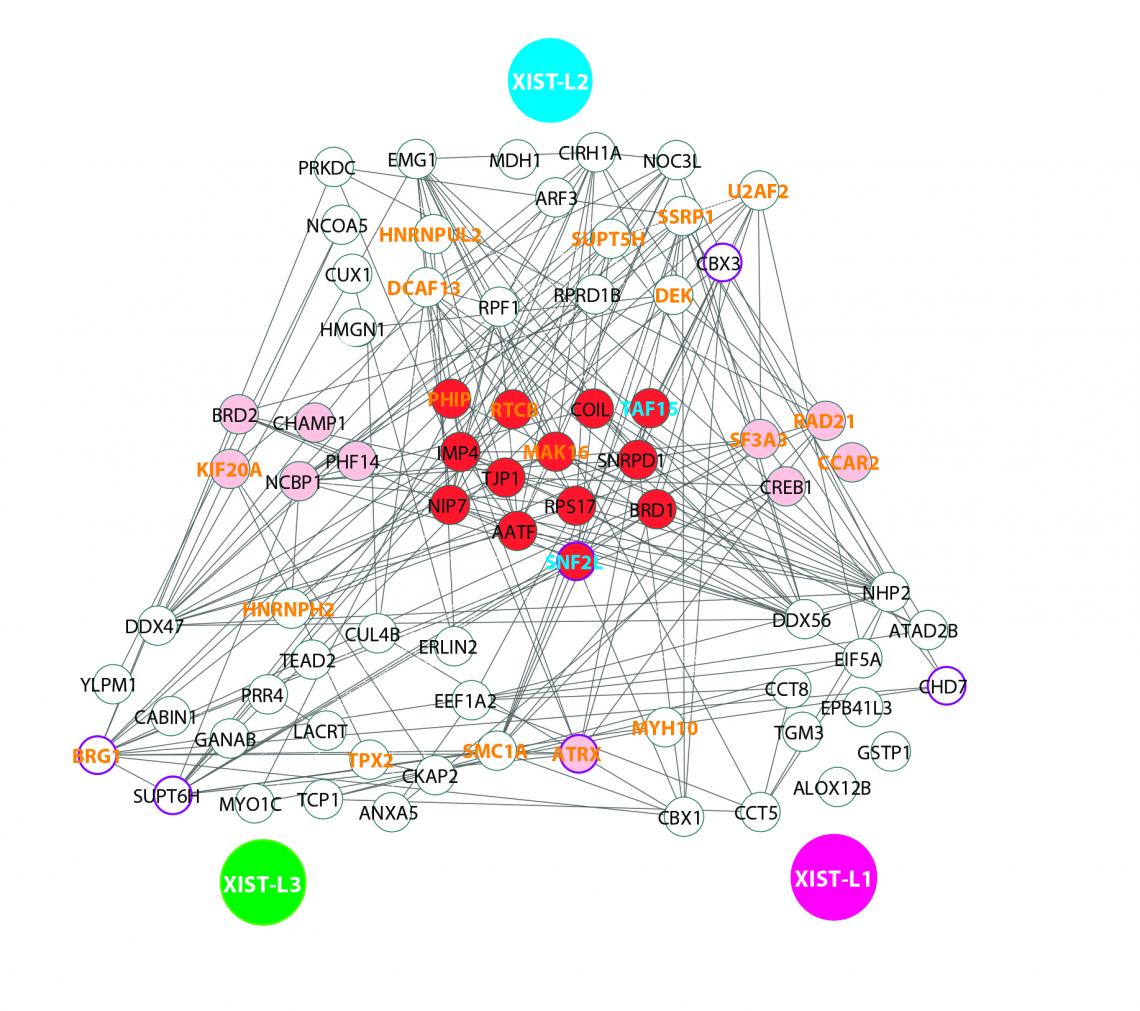

Powered by the proteomic (analysis of the protein) technique developed by Dr Zhang, the team was able to find and validate two previously uncharacterized binding proteins of a lncRNA in mammalian cells.

The team applies CARPID on different spots (L1, L2, and L3) of the same lncRNA (XIST) to find the binding proteins. Previously reported XIST-associated proteins are highlighted in bold orange font. The two previously uncharacterized binding proteins of XIST, namely SNF2L and TAF15, are indicated in blue font. (Photo source: DOI number: 10.1038/s41592-020-0866-0)

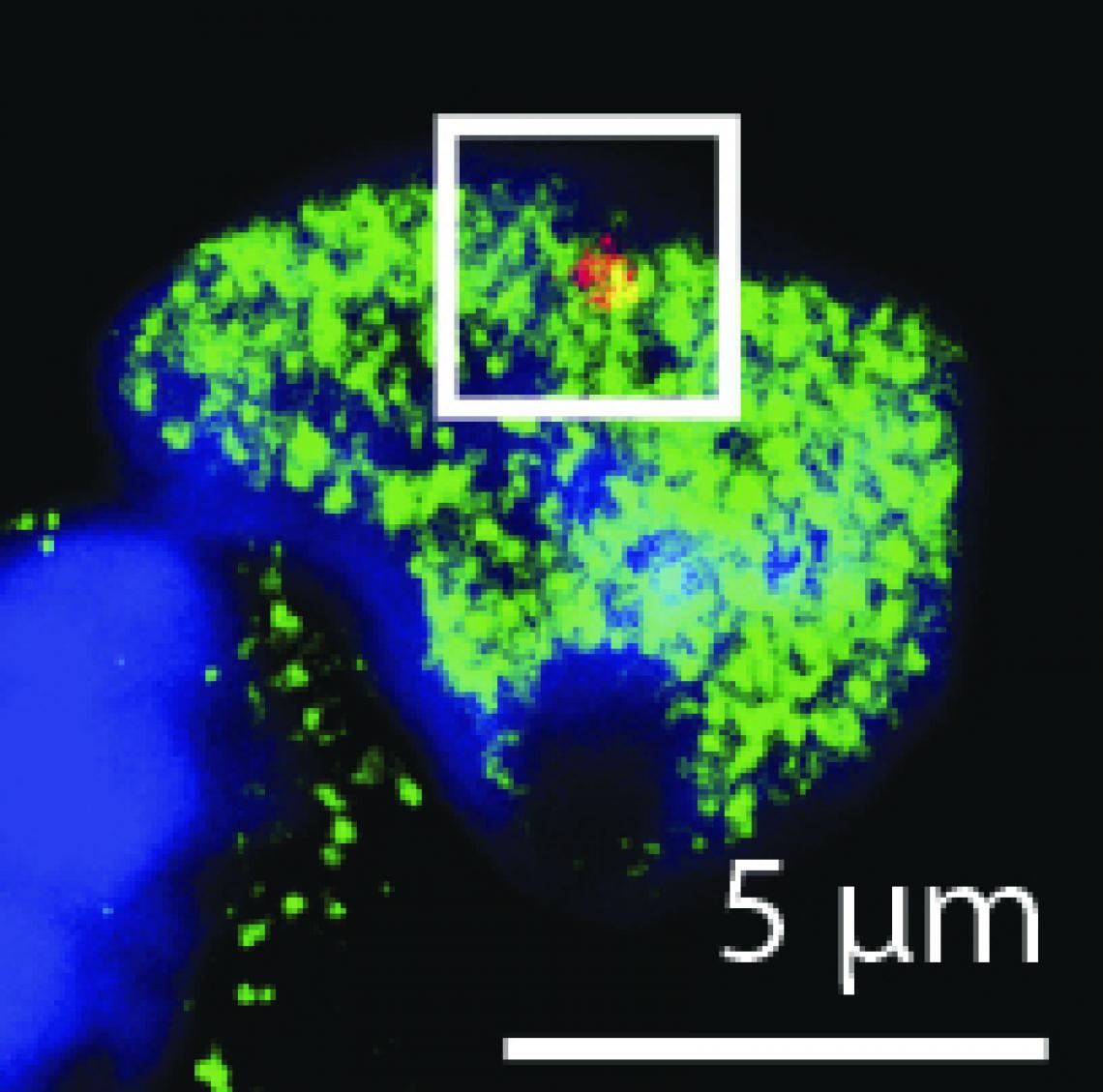

Red signals in the picture represent XIST lncRNA and the green signals are from TAF15 protein, one of the previously uncharacterized binding proteins. Yellow signals indicate the overlapping of TAF15 and XIST lncRNA, which means they bound. (Photo source: DOI number: 10.1038/s41592-020-0866-0)

Enables detection of the binding proteins of viral RNA

The team believed CARPID has broad application, including the detection of the binding proteins of viral RNA. “For example, SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus that causes COVID-19. Once the virus infects cells, we could apply CARPID to detect what cellular proteins are recruited by this virus for the viral life cycle. If we depleted the binding proteins, we are likely to suppress the viral replication. This information may help us identify potential antiviral drug targets,” Dr Yan elaborated.

Moreover, many lncRNAs are used as diagnostic biomarkers for cancer as they become more abundant in cancer cells than normal cells. CARPID can be applied to detect the binding proteins of these lncRNAs in cancer cells that may help find tumorigenic mechanisms and potential protein targets for cancer diagnosis or treatment.

It took the team about one year to develop CARPID and most of the experiments were done in CityU. Their next step would be trying to apply it to research on stem cell and DANCR, a lncRNA that generally works as a tumor promoter.

Dr Yan, Dr Zhang, and Dr Chan Kui-ming (who contributed to validating CARPID) are the corresponding authors of the paper. The co-first authors of the paper are Li Jingyu and Zhu Xiaoxuan from the BMS department, together with Yi Wenkai and Dr Wang Xi, both from Northwest University in Xi’an.

The study was supported by CityU, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Shenzhen Science and Technology Fund Program, Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Opening Foundation of Key Laboratory of Resource Biology and Biotechnology in Western China, the Chinese Ministry of Education and the EpiHK consortium.

DOI number: 10.1038/s41592-020-0866-0

Members of the CityU research team, (front row from left) Dr Zhang Liang, Dr Yan Jian, Dr Chan Kui-ming, (back row from left) Fan Ligang, Yi Wenkai, Zhu Xiaoxuan, and Li Jingyu. (Photo source: City University of Hong Kong)