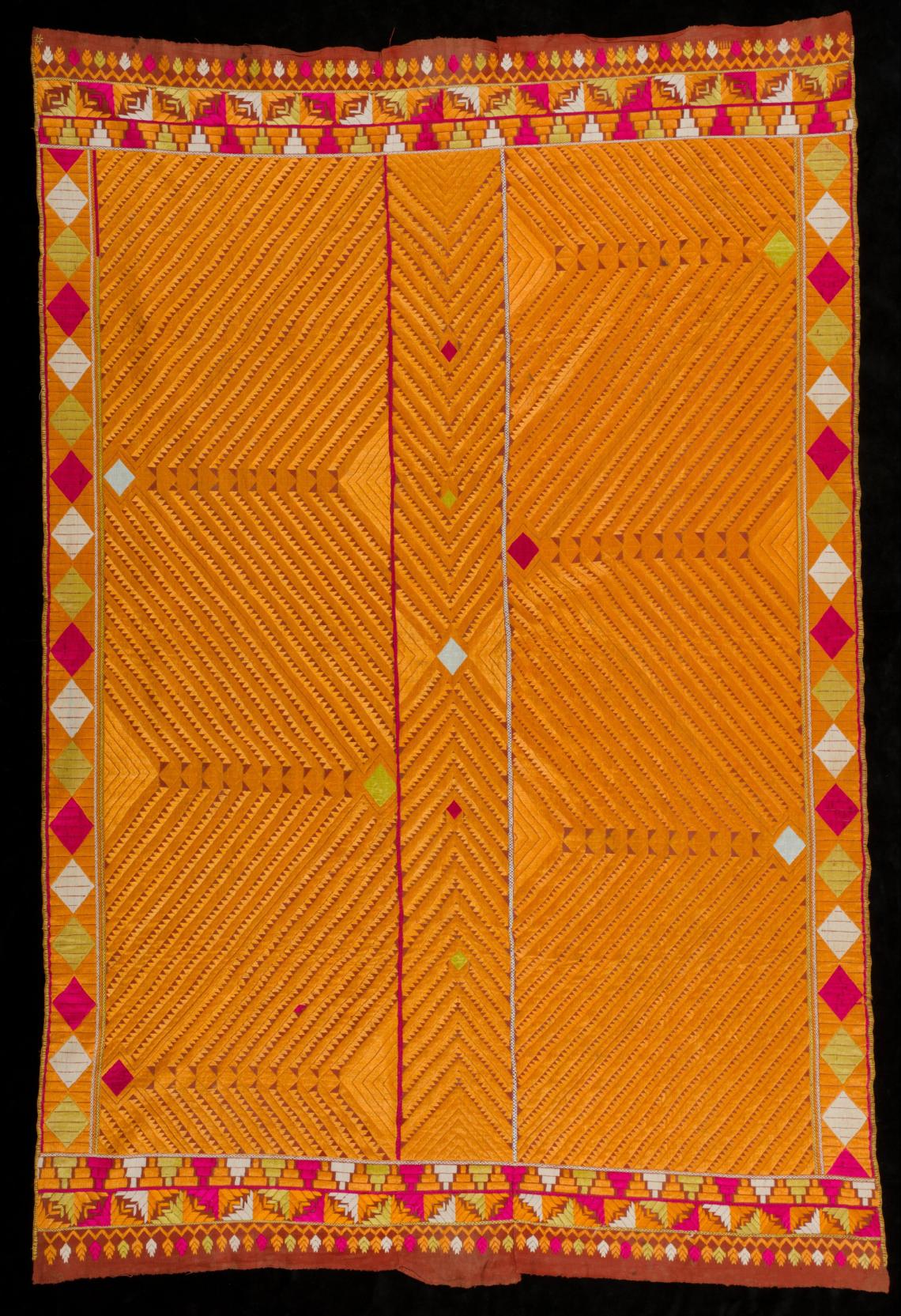

Vari Da Bagh with large colourful diamonds and smaller all-over self-design diamond pattern, Undivided Punjab, India, c. 1930s, Cotton, floss silk, 118 x 234 cm.

A textile tradition practised in the Punjab region of India and Pakistan as well as in Haryana, bagh embroidery is ritually important and used to decorate textiles such as chaddars and odhnis, which are also referred to as baghs. The term derives from the Hindi bagh, meaning “garden,” owing to the thick layer of embroidery and the representation of monumental gardens on some baghs.

Baghs are similar to phulkaris — both textiles use silk embroidery thread, the darning stitch, a similar colour palette and have the same historic centres of production. Like phulkaris, baghs are generally made to celebrate occasions such as births and weddings. However, bagh embroidery almost completely covers the base cloth, which is visible only as thin lines in the design. The base cloth is often chaunsa khaddar, a finer version of the red cotton base fabric used in phulkaris.

There are several types of baghs, which are often named after key aspects of everyday life and culture in Punjab. Those used in wedding rituals include vari da bagh, gunghat bagh and sar pallu. Baghs are frequently named after their motifs: leheriya and darya baghs feature water motifs; the chandrama bagh, which uses moon motifs, is worn during Karva Chauth rituals; the tota bagh features parrot motifs; and the belan bagh depicts rolling pins — a key instrument of domestic life in north India. Since Punjab has historically been an agrarian region, some baghs use motifs of important vegetable crops, such as the karela (bitter gourd) , mirchi (chilli), gobi (cauliflower), dhaniya (coriander) and kakri (cucumber) baghs. The genda, chameli and surajmukhi baghs are named for the flowers that are used as motifs. Certain baghs, such as the Shalimar and Chamasia baghs, are named after the historic gardens they depict or the general composition of a Mughal garden, such as the char bagh. Possibly the most elaborate type is the bawan bagh, which features between forty-two and fifty-two rectangular cells decorated with geometric motifs. Pachranga and satranga baghs are named on the basis of the number of colours in the design.

Self-design diamond patterned Vari Da Bagh, Undivided Punjab, India, c. 1930s, Cotton, floss silk, 133 x 254 cm.

Bagh embroidery is time-consuming, taking several months to a year to complete. Today, they are not typically made by families, which was traditionally the mode of production; instead, they are procured from retail outlets or have been replaced by heirloom baghs for ceremonial use. Examples of historic baghs are held in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Featuring rich bagh embroidery, vari da bagh is a type of chaddar or shawl used in Punjabi wedding ceremonies, its name translating literally to ‘garden of the wedding trousseau’. This bagh from north India has a main field embroidered with gold-coloured silk thread, while the borders are made with a variety of colours. Thin gaps are left between the shapes so that the red base fabric, either chaunsa khaddar or halwan, shows through as an outline. The design is composed entirely of geometric forms, the central field typically embroidered with repeating concentric diamond shapes, with a complementary pattern of diamonds and zigzag lines along the borders. While vari da bagh designs often feature a repeating block of two concentric diamonds, more elaborate ones feature three concentric diamonds, with the innermost diamond further subdivided into four parts. In some cases, the diamond shapes are made of concentric triangles.

Zigzag-patterned Bagh, Pakistan, Early to mid- 20th century, Cotton plain weave with silk embroidery, 205.7 x 137.2 cm.

As with some other types of phulkaris and baghs such as the shishedar phulkari and the chope, the patterns on a vari da bagh may be broken by a nazarbuti in the form of a small row of black threads embroidered in a random position in one of the diamond shapes. This motif, as well as a black dot commonly introduced in a corner of the fabric, is intended to ward off the evil eye or bad luck for the wearer.

In traditional Punjab, the grandmother of a boy begins to prepare a vari da bagh shortly after his birth. The embroidery is started on an astrologically auspicious date, accompanied by festivities. Years later, the completed bagh is draped around his bride just after their wedding ceremony. The bride also wears it during the vidaai or doli, when she ceremonially leaves her parents’ home. Married Hindu Punjabi women traditionally wear a vari da bagh chaddar, either their own or one passed down as an heirloom, when praying for their husbands’ well-being during Karva Chauth rituals.

Vari da baghs usually take years to embroider. While new pieces are rarely made today, some are sold through retail outlets. Examples of historic vari da baghs can be found in the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.