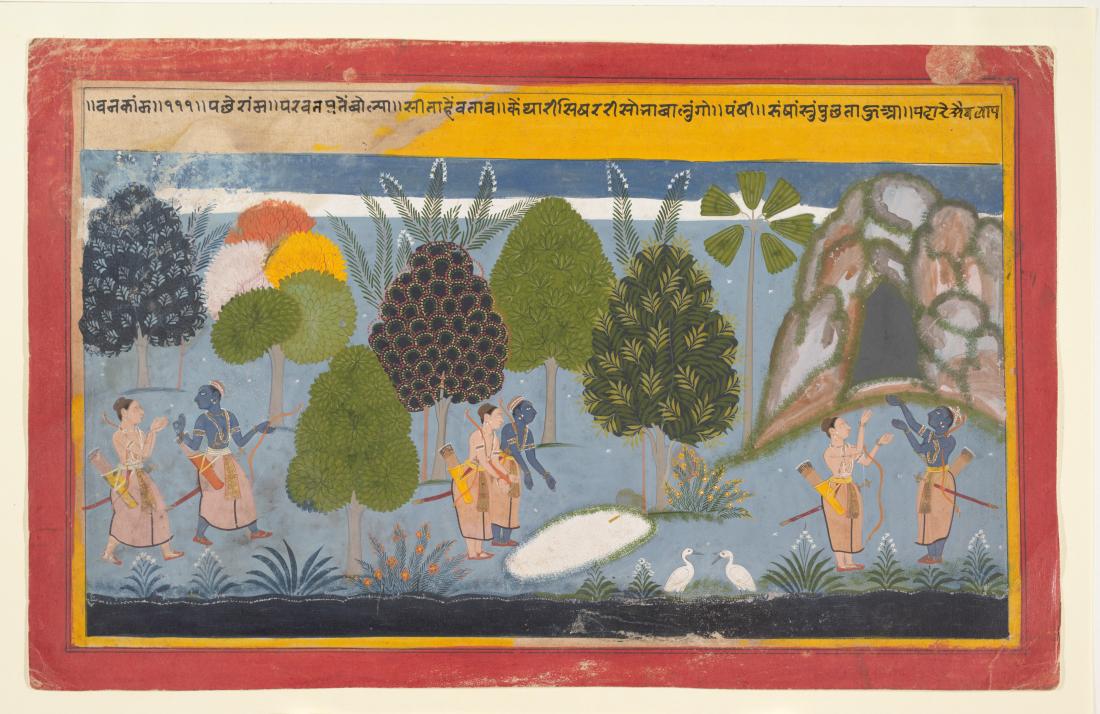

Rama and Lakshmana Search in Vain for Sita (Illustrated folio from a dispersed Ramayana series), Mewar, Rajasthan, India, c. 1680–90, Ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 26 x 41.3 cm.

A tradition of miniature painting that emerged in western India in the seventeenth century, the Mewar school was patronised by the Sisodia dynasty. The dynasty ruled over the Rajput state of Mewar in present-day Rajasthan, which included districts such as Bhilwara, Udaipur and Chittorgarh, as well as adjacent parts of present-day Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. The royal atelier at Udaipur, the Sisodias’ capital from 1615 onwards, produced paintings spanning several genres but was especially prolific in the field of portraiture. Mewar painting was unique in its evolution as a distinct style — following Mewar’s steady resistance of Mughal subjugation — while older Rajput painting traditions such as the Malwa school were incorporating elements of the Mughal miniature tradition by the beginning of the eighteenth century, and newer schools like those of Bikaner and Kishangarh emerged from it.

The defeat of Rana Sanga (r. 1509–27) at the hands of the first Mughal emperor Babur (r. 1526–30) in 1527 led to nearly a century of conflict in western India, culminating in a peace treaty between Amar Singh (r. 1597–1620) and Jahangir (r. 1605–27) that codified the unique position of the maharanas or rulers of Mewar. This also spurred a period of prosperity for the kingdom, particularly during the reign of Karan Singh II (r. 1620–28) and his son Jagat Singh I (r. 1628–54). The latter was a noted patron of painting and commissioned several illustrated manuscripts with the intention of replenishing the royal library, whose collection had been damaged during the siege of Chittor in 1567–68. These manuscripts spanned different genres, from religious and secular poetry to historical and genealogical texts.

From the twelfth century onwards, manuscript illustrations accompanying religious texts such as the Bhagavata Purana or the Gita Govinda, and poetic works such as the Vasanta Vilasa, became the predominant genre of art in western India. This Western Indian style of painting was characterised by a strictly two-dimensional perspective articulated in a flat division of space; angular human forms; and faces in profile with the subject’s further eye protruding into space. While the style flourished under the patronage of affluent Jain individuals, it also remained static but that served a conservatory purpose for the region’s artistic idiom against the growing influence of the art styles of the Mughals and the Delhi and Deccani sultanates. In the fourteenth century, the Early Rajput style of painting emerged out of this, showing more fervent emotional expression than the Western Indian style. It used bold primary colours, floral patterns and symbolism within a strict division of space, and did away with the protruding further eye. The finest examples of the Early Rajput style can be found in the Chaurapanchasika paintings. Fifteenth-century illustrated Jain texts following the conventions of the Early Rajput style have also been found in Mewar, underlining the prominence of Jainism and a well-established manuscript illustration practice in the region.

Maharana Jagat Singh II in Procession, Mewar, Rajasthan, India, c. 1745, Ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 39.2 x 29.2 cm.

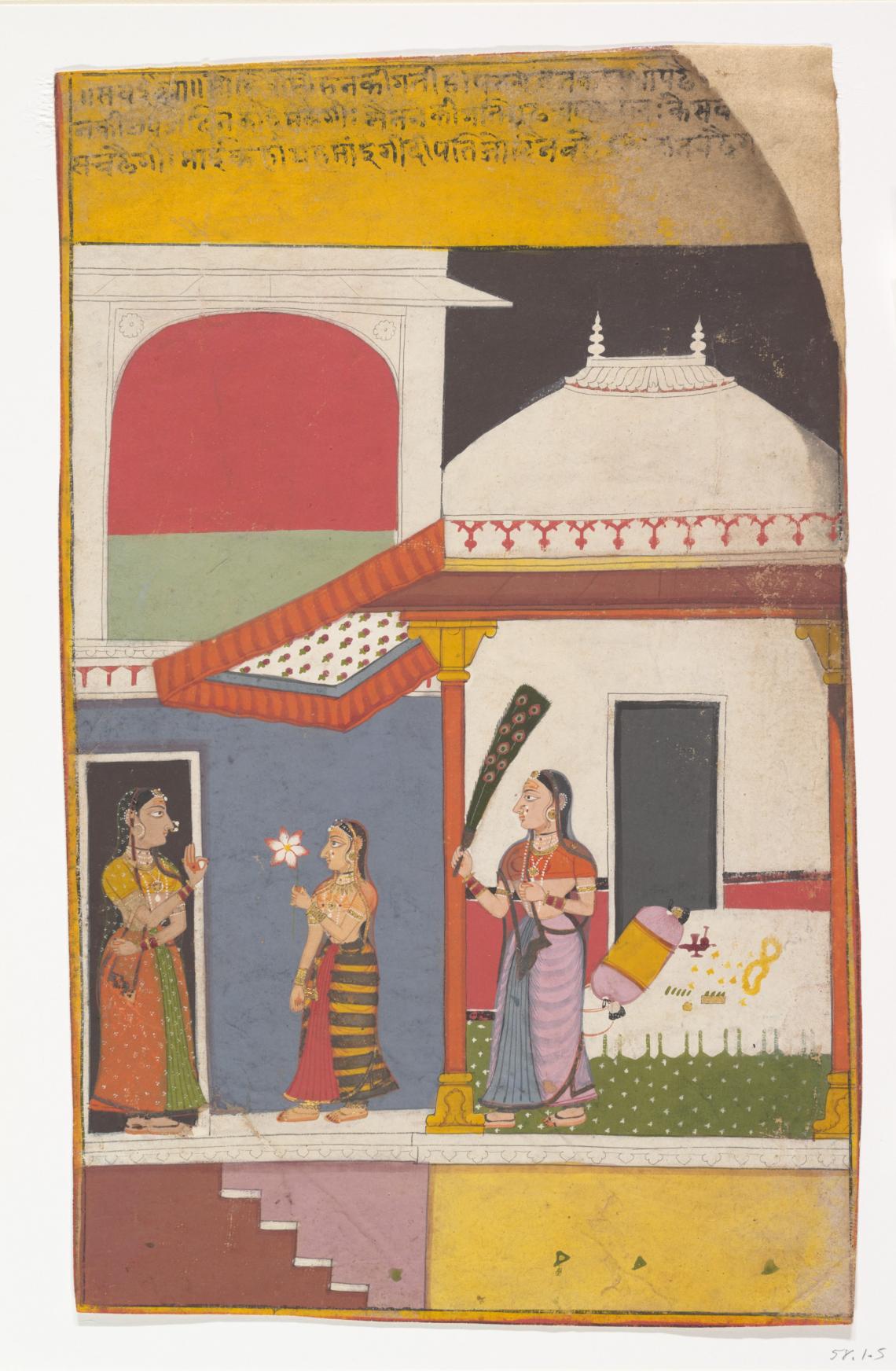

The paintings associated with the Mewar school are characterised by confident lines and an earthy palette of colours such as ochre and olive, punctuated by occasional bursts of vivid colour, especially prominent shades of red. The faces of gods, Rajput figures and other Hindus are rendered in a strict profile view revealing only one eye, connoting nobility and grace. In contrast, depictions of foreign subjects such as Muslims or Europeans employ the do-chashmi (‘two-eyed’) perspective showing the further eye, either in a three-quarter or frontal view. Landscapes are rendered in great detail, deriving from Mewar’s context as a region of fertile plains dotted with gardens and buildings and flanked by the Aravalli range to its west.

The earliest dated manuscript associated with the Mewar school is the Chawand Ragamala series of 1605, painted by the artist Nasiruddin. Chawand was the temporary capital of the Sisodias during their conflicts with the Mughals in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and it was there that the manuscript was produced. Scholars consider this Ragamala series to be exemplary of the evolution of the Mewar school of painting from the Early Rajput style into a distinct one in its own right. This Ragamala is notable in its use of vibrant colours, similar to Chaurapanchasika paintings, and assured lines, as well as its deeply symbolic iconography. The human forms are noticeably less angular than previously seen in paintings from the region while architectural, decorative and natural elements are highly detailed. Nasiruddin also adopted the vertical layout typical of Mughal paintings in this series.

In the seventeenth century, religious and mythological illustrations, as well as glorified depictions of the Sisodia dynasty’s history dominated paintings produced by the royal atelier. In the first half of the century, under the patronage of Jagat Singh I, the Udaipur atelier was dominated by the works of the master artist Sahibdin, who produced works across genres. Sahibdin’s style drew from existing painting traditions in the region, and incorporated some elements from the more popular Mughal school, particularly those of composition. These innovations heralded the maturation of the Mewar style and defined the template for manuscript illustration in the atelier for several subsequent decades. He built on Nasiruddin’s use of colour to enhance the rasa or emotional tone of paintings, as seen in his Ragamala series from 1628, which is among his earliest works. His renderings of the Gita Govinda (1629, 1635) are celebrated for their minutely detailed portrayal of foliage. Other works of his include a Rasikapriya (c.1630) and a Bhagavata Purana (1648). His Suryavamsha (1645) initiated a tradition of depicting the mythical ancestry of the Sisodias in paintings.

One of the most notable works from the latter part of the seventeenth century is a Ramayana (1649–53), considered to be one of the most ambitious projects of the Mewar school. Six of the seven books of the Ramayana were illustrated by three groups of artists led by Sahibdin and another artist influenced by his work known as Manohar of Mewar. Another large-scale manuscript project undertaken by the atelier at Udaipur was a Mahabharata executed in the second half of the seventeenth century by an artist named Allah Baksh. This manuscript demonstrated the artist’s uncharacteristically vibrant colours and his unique idiom of depicting scenes from the Bhagavad Gita in vertical compositions while the rest of the Mahabharata was rendered in horizontal ones.

Page from a Dispersed Ragamala Series (Garland of Musical Modes), Mewar, Rajasthan, India, c. 1710, Ink and opaque watercolour on paper, 28.6 x 17.5 cm.

During the reign of Amar Singh II (r. 1698–1710), there was a marked shift in subject matter — court scenes became more favoured; portraiture assumed an unprecedented significance; and manuscript illustration declined. These changes entailed an evolution of style, in which greater visual depth, distant horizons and more natural colours became commonplace. A prolific master artist of the period was an anonymous artist now known by the epithet of Stipple Master. He worked closely with the king, producing a number of court scenes and equestrian portraits of Amar Singh II. A number of works attributed to the Stipple Master depict his patron in intimate, leisurely settings, signalling that the artist might have held a distinguished rank in the court, which granted him considerable access to the king’s private life. His works are characterised by monochrome settings, often with minimal backgrounds, in which only human and animal figures, trees, and sections of architecture are rendered in colour and given depth using stippling, in the nim qalam style he is known to have pioneered in Udaipur. The popularity of this style waned in the early eighteenth century.

In the following two decades, during the reign of Sangram Singh II (r. 1710–34), manuscript illustration underwent a revival. Some of the prominent manuscripts illustrated during this time include Bihari Lal’s Sat Sai (c. 1719) and Surdas’s Sur Sagar (c. 1750). Sangram Singh’s rule and that of his successor Jagat Singh II (r. 1734–51) are considered to form the last significant phase of paintings produced to illustrate religious manuscripts within the Mewar school. This period was also characterised by the emergence of the genre now known as tamasha painting, one that would dominate the Mewar school for the following two centuries. Executed on large sheets of paper by two or three artists and offering a panoramic scope, these paintings recorded hunts, festivals, processions and elaborate court scenes in fine detail. A number of works made during the reign of Sangram Singh II are attributed to an artist named Jai Ram, whose expertise spanned the genres of portraiture and tamasha paintings. According to scholars, Jai Ram’s close eye for detail and preference for cool colour palettes suggest a training in the Mughal school of miniature painting.

The eighteenth century also saw the emergence of the Nathdwara sub-school in Mewar painting, which focussed on devotional themes. Centred around the Shrinathji Temple, a Vaishnava pilgrimage site in Nathdwara, these paintings were primarily executed on cloth. While it was affiliated to the Mewar school and under the protection of the maharanas, the Nathdwara genre emerged as a distinct school, incorporating elements from the painting styles of several other Rajasthani courts including Amber and Marwar. The subjects of these paintings are mythological episodes from the life of Krishna, featuring him amidst lush landscapes, accompanied by his consorts, or gopis, who are all rendered with homogenous features.

Due to political flux, painting in the court at Udaipur declined in the second half of the eighteenth century, with several artists leaving the workshop altogether. One such artist was Bagta, who moved to Deogarh, which was administered by the Rawat clan, consisting of members of Mewar’s nobility. Bagta was renowned for his innovative style, which challenged the conventions of court painting of the time. Apart from carefully studied portraits of the Rawat rulers, he also painted hunting scenes in which the landscape was represented in an aerial view, similar to the works produced in Udaipur. In these paintings, humans are dwarfed by their imposing surroundings, which are depicted in a deep green and studded with rocks, while animals are scattered in large numbers across the frame. His son Chokha carried forward his style of painting in the early years of the nineteenth century. Both Bagta and Chokha were seminal in rejuvenating the Udaipur atelier and restoring the tradition of painting after it had witnessed a steady decline during the period of the kingdom’s weakening. Chokha’s paintings during the middle years of Bhim Singh’s (r. 1778–1828) rule developed an erotic style in their voluptuous depictions of human figures. This evolution became emblematic of the maharana’s indulgent lifestyle, with paintings of the period often portraying him in intimate scenarios. Chokha experimented with a variety of genres and styles following his return to Deogarh around 1811.

The remainder of the nineteenth century, marked by the increasing political influence of the British in the region, saw stagnation in the artistic legacy of the Mewar school as paintings continued to follow the conventions set a century earlier. Among the last notable painters of the school was Tara, noted for his large-scale works and use of multiple perspectives. With the arrival of photography during this period, his works signify the final phase of painting as the sole official medium of courtly documentation in the Mewar court. A brief artistic evolution occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century, prompted by the visits of British artists such as William Carpenter, Val Prinsep and Marianne North. However, by this time the manuscript painting tradition in Udaipur had waned significantly and court portraiture was being steadily replaced by photography.

Today, works from the Mewar school such as manuscript illustrations, portraits and tamasha paintings are housed in museums and private collections across the world, including the City Palace Museum and the Government Museum in Udaipur; the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.