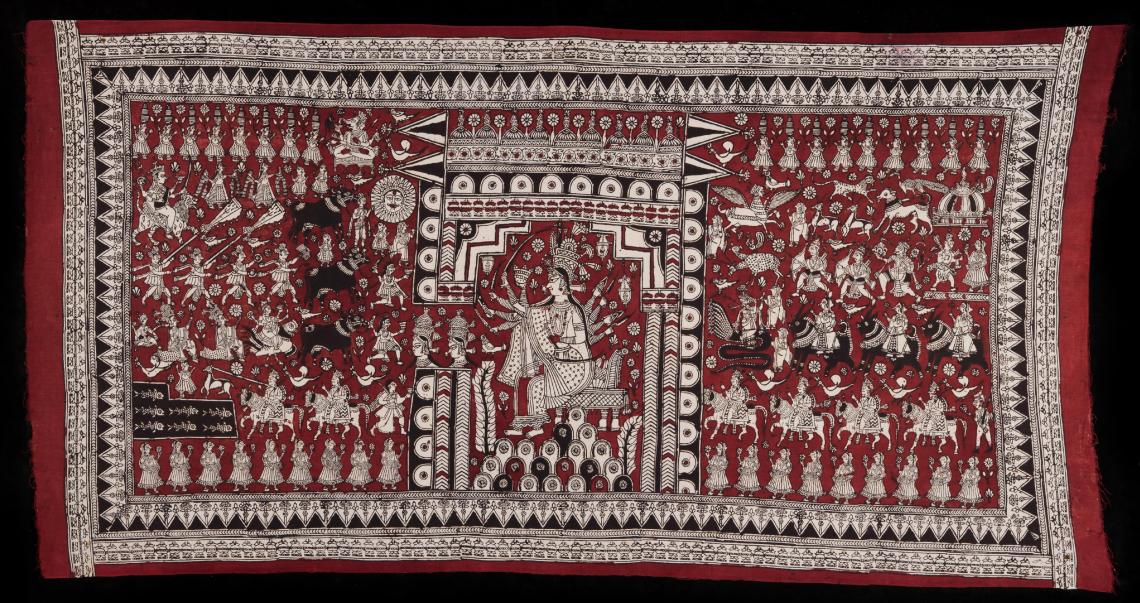

Mata-ni-Pachedi, Gujarat, India, Late 20th century, Cotton, natural dyes, 173 x 280 cm.

A form of traditional cloth-painting made for the worship of matas, or goddesses, mata ni pachedi is associated with western India’s nomadic Vaghri community, which has traditionally lived along the banks of the Sabarmati river in Gujarat. As members of this non-dominant caste were not allowed to enter temples, they began creating these paintings around three hundred years ago as part of their own shrines for worship. Deriving their name from the Gujarati for ‘shawl of the goddess’ or ‘goddess backdrop’, mata ni pachedi paintings were traditionally used as canopies and backdrops in temporary wooden shrines, and also formed objects of devotion themselves. They depict a Hindu goddess signifying shakti, or power, as the central figure, situated within an enclosure demarcating a temple, and surrounded by numerous other figures. The paintings are narrative in style, like those from the Phad tradition in Rajasthan and Kalamkari paintings from South India, and depict events from mythological texts, epics, religious processions and even historical themes such as Gujarat’s ancient sea trade.

Mata ni pachedi is usually made on a rectangular fabric, which is divided into seven to nine columns to create a grid for the narrative to unfold. The grid is structured by architecture-like insertions that reproduce windows, doors and archways in a stylised form. Traditionally, the colours used were naturally procured and processed, and consisted of a visual scheme of masoor (red) and black on a white cloth — the red extracted from alum, alizarin, tamarind and dhawadi (Woodfordia fruticosa) flowers, and the black from jaggery and iron rust. Before painting, the cloth is soaked, washed, de-starched and treated with a harda (Terminalia chebula) solution. Both woodblock printing and hand painting are used to create mata ni pachedi paintings. While woodblocks are usually used for the borders, many drawings, embellishments and motifs are painted with a bamboo kalam (pen), and a brush in more recent times.

Mata-ni-Pachedi, Gujarat, India, Late 20th century, Cotton, natural dyes, 127 x 128 cm.

In mata ni pachedi the figure of the goddess has a commanding presence, depicted flanked by worshippers, musicians and animals. Many forms of the goddess –– known through mythological and oral narratives, textual sources, and popular local traditions –– are found in these images, including various representations of the goddesses Durga and Amba. Also included are goddesses from the local folk tradition of Gujarat, such as Vishat Mata, one of the most important goddesses for the Vaghris, who claim their ancestry from her; Vahanvati Mata, who is worshipped by seafarers and traders; Momai Mata, more popularly known as Dashamaa, a goddess of the Kutch region and protector of health, livestock and harvest; Khodiyar Mata, who is thought to be powerful enough to predict the nature of incoming monsoon; and Hadkai Mata, who protects her flock from rabies. The pantheon of such local goddesses in the mata ni pachedi tradition serves to illuminate the social and cultural life of the Vaghris as a nomadic agricultural community dependent on monsoon rains, as well as Gujarat’s history of maritime trade.

Images of the goddesses in mata ni pachedi generally follow traditional iconographic conventions. In some versions, the Hindu god Ganesha appears in either the upper portions of the cloth or to the left of the goddess. Narratives from Mahabharata and Ramayana also find a portrayal, with artists improvising and adapting scenes from the texts to fit them into the mata ni pachedi painting conventions. For instance, the golden deer from the scene of Sita’s abduction in Ramayana is depicted instead simply as a two-headed deer since the colour gold was not available as a natural dye. Similarly, the game of dice from Mahabharata was substituted by a game of cards as the latter was easier to illustrate.

Kalamkari: Mata-ni-Pachedi (Shrine cloth for the mother goddess), Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, 20th century, Painted cotton, plain weave, 254 x 129.5 cm.

The need to improvise and adapt the form has led to significant changes in the artform; the grid-like structure for the narrative is no longer a requirement, and traditional depictions of rows of worshippers carrying garlands and flags have been supplemented by angels carrying them. In some cases, the temples also appear to be domed like mosques. To reduce costs and meet increased demand during the festive season, mata ni pachedi artists today have replaced natural dyes with a vast array of artificial colours, such as sap green, yellow ochre and dark blue.

The popularity of mata ni pachedi is no longer restricted to its ritual aspect and its significance during the nine-day Hindu festival of Navaratri. Artists now produce decorative consumer goods such as bedsheets, pillowcases, wall hangings and garments in the traditional style all year round.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.