Balarama, Subhadra and Jagannath in the temple at Puri, Oil painting by a painter of Puri, Odisha, c. 1880/1910.

A painting tradition of Odisha and West Bengal, Pattachitra is most closely associated with the Jagannath Temple at Puri. The art form derives its name from the Sanskrit words patta(cloth) and chitra (image) and likely dates back to the twelfth century, the period when the Jagannath Temple was built. In Odisha, the artists or chitrakars who make these paintings belong to the Mahapatra and Moharana communities, and historically lived in the area immediately around the temple.

The paintings, which are made on cloth, depict scenes from Hindu mythology – particularly stories of Jagannath, Krishna and Ram – and are considered to have religious value by devotees. The subject matter is drawn from a canonical set of narratives, such as the adventures of Krishna as a child; the Dashavatara, or stories of Vishnu’s ten incarnations; the Kanchi Abhijana, a fifteenth-century war against Kanchi by the Odia king Purushottama Deva; Kaliya Dalan Vesha, the story of Krishna defeating the serpent demon Kaliya; and the war between Ram and Ravana as narrated in the Ramayana. Some non-narrative subjects include the Kandarpa Ratha, an image of a chariot driven by Krishna and several women; Panchamukhi Ganesh, a depiction of Ganesh with five heads; the Thia Badhia, a layout of the Jagannath Temple; and Navagunjara, a chimeric creature made of nine different animals that is believed to be an avatar of Vishnu.

The canvas for a Pattachitra is made by glueing two cotton sheets together with tamarind gum. The side to be painted is treated with a mixture of more tamarind gum and powdered limestone, after which it is dried and polished. Today, two sets of brushes are typically used: squirrel or rat hair brushes for thin outlines, and buffalo hair brushes for thick lines and filling colour. The paintings are coloured with natural pigments. Blue is obtained from indigo, yellow from haritala, red from hingula or geru clay, black from soot, green from crushed leaves and white from powdered conch shells. These colours are fixed to the canvas using a medium of kaitha (wood apple) gum and coconut water.

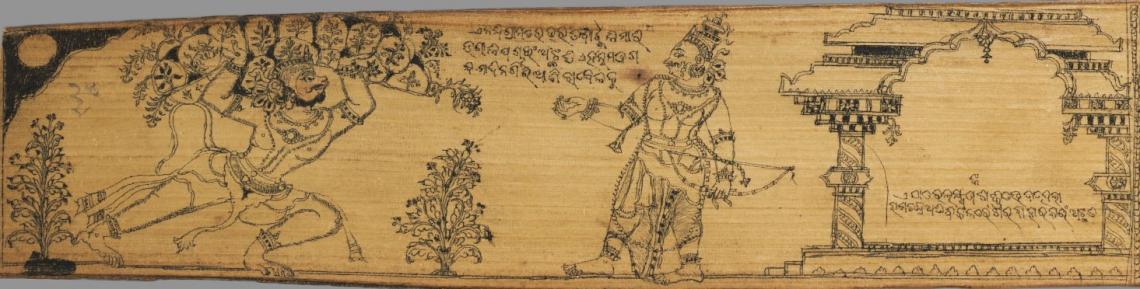

The Monkeys and Bears Fight Ravana and His Demons, Odisha, India, Black ink and yellow pigment on palm-leaf, c. 1750.

The figures depicted in pattachitra paintings are typically shown in profile, with long, tapering eyes, pointed noses and rounded chins. The shape of the eye is used to suggest subtleties of mood and artists may choose from up to twenty-one different variations. While there is usually no landscape or background in a painting, foliage and minor details are sometimes added on the ground directly around the feet of the figures. A pattachitra is started with the border, which consists of intricate floral and curvilinear patterns. The border uses the same colour scheme as the scene to be depicted, making each border unique to its painting. While most deities are painted in the traditional colour association with them – such as Krishna in blue or Ram in green – the skin colour of other figures is guided by the moods prescribed in rasa theory. Characters in a state of raudra or anger are portrayed in red, adbhuta or puzzlement in yellow and those in hasya or a humorous mood are portrayed in white.

On the full moon day of the Hindu month of Jyeshtha, the three principal idols of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra are removed from their sanctums at the Jagannath Temple and given a ritual bath prior to the annual rath yatra or chariot procession. The idols are then retired for fifteen days, a period known as anasar. During this time, three newly-painted pattachitra (also known as the anasar patti) depicting each of the gods are placed in their respective shrines. Jagannath is painted in black, Balabhadra in white and Subhadra in yellow. Apart from these, smaller pattachitra known as jatri patti or yatri patti, which draw from a wider pool of narratives, are sold to pilgrims visiting the temple as keepsakes.

While pattachitra was a male-dominated profession historically, today there are also many women who paint full time. The tradition has been expanded to include artists from non-chitrakar families as well. In addition to being sold to visitors at the Jagannath Temple, pattachitra paintings are also sold across Odisha as souvenirs for tourists.

This article first appeared in the MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit online platform consisting of an Encyclopedia of Art, Courses and Stories, that encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts and histories of South Asia. Our team of researchers, editors, writers and creatives are united by a shared goal of creating more equitable resources for the study of art histories from the region.