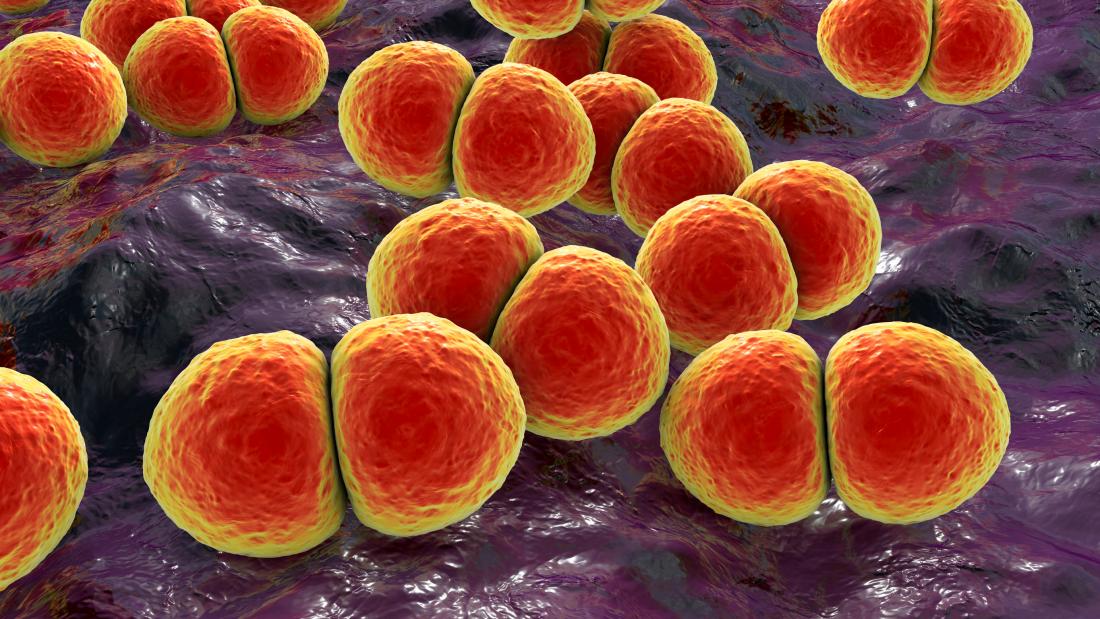

It is estimated that one million children die every year of pneumococcal disease, caused by the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria seen here.

This story is featured in the Asia Research News 2022 magazine. If you would like to receive regular research news, join our growing community.

Get the news in your inbox

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Antimicrobial Resistance

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a staggering number of deaths and illnesses, and an immense economic burden worldwide. But the awareness of the importance of infection prevention and control it has created, and the rapid global response it triggered, could be a blessing in disguise for the war against a more insidious pandemic that has been around for much longer.

In 2019, the World Health Organization declared antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as one of the top ten global public health threats facing humanity. Many bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi have adapted over time to develop resistances to some of the life-saving antimicrobial drugs discovered since the early 20th century. This natural process of adaptation has been accelerated by the misuse and overuse of these drugs. Infections by drug-resistant microbes were predicted to cause 700,000 deaths a year but the actual number may be much higher based on a recent study (see next story). Scientists predict that this number will rise to 10 million deaths every year by 2050, with a global economic loss of US$100 trillion, if no action is taken.

On December 7, 2021, a webinar on this issue was hosted by the Asian Development Bank Southeast Asia Development Solutions (SEAD), the International Vaccine Institute, Institut Pasteur Korea, the International Centre for Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions (ICARS), and the Embassy of Denmark in Korea. Titled “Curbing the invisible pandemic: Effective solutions to collectively combat antimicrobial resistance”, the webinar brought together a large panel of experts to highlight the potential solutions and national action plans being developed to tackle this global problem.

Did you know?

Antibiotic resistance happens when bacteria adapt to avoid destruction by antibiotics. Antimicrobial resistance is a much broader term that encompasses bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites, and the cornucopia of drugs used to combat the infections they cause.

One globe, one health

“In order to solve the issue of AMR, a joint initiative is required that incorporates not only humans, but also animals, food and the environment; the so-called One Health approach,” said Eun A Her, member of the Korean National Assembly Science and Technology Information Broadcasting and Communications Committee.

According to the WHO, people infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are 64% more likely to die than those infected with the drug-sensitive kind.

One Health is a holistic and multi-sectoral approach for combating AMR by designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research that recognize the interconnectivity of human, animal and environmental health.

ICARS was established in Denmark in November 2021 to apply this One Health approach to research that tests context-specific solutions for AMR in low- and middle-income settings.

“Low- and middle-income countries will be severely affected by AMR, as these are places where there is less access to clean water, sufficient sanitation and hygiene, as well as affordable medicines and vaccines,” explained Einar Jensen, an agricultural scientist and Denmark’s ambassador to Korea.

AMR is highly complex, as it does not respect geographic or human-animal-environment boundaries, explained Robert Skov, ICARS’s scientific director. Complicating the issue further, as countries become more developed, they inevitably use more antibiotics, which exacerbates the problem. On the other hand, the lack of access to antibiotics in less developed countries leads to more deaths than those caused by infections with drug-resistant bacteria, he said.

“So what needs to be done? We definitely need new antibiotics and new vaccines,” said Skov. He adds, however, that we also need to protect what we already have by developing strategies for the rational use of antimicrobial drugs, as well as for infection prevention and control, and biosecurity.

The roles of vaccines and new drugs

AMR is a high research priority for the International Vaccine Institute (IVI). Antimicrobial drug use drops when vaccinated people are protected against infectious diseases. This happens by directly reducing the incidence of disease, but also by indirectly reducing the misuse of antibiotics that is often seen in connection with viral infections, explained Marianne Holm, IVI’s head of epidemiology and public health research.

Currently, there are very few licensed vaccines that target priority and potentially drug-resistant pathogens. There is also insufficient rollout of the few vaccines that do exist, said Holm. So it’s important to make better use of the existing vaccines that target the Streptococcus pneumonia (which causes sepsis, meningitis and pneumonia) and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi bacteria (which causes typhoid fever), and the Haemophilus influenzae type B virus (which causes influenza).

Evidence already demonstrates the impacts of these vaccines in reducing AMR diseases. In South Africa, the incidence of antibiotic-resistant invasive pneumococcal disease in children under the age of two dropped significantly after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in 2009 and 2011. In Pakistan, the typhoid conjugate vaccine was key to defeating an outbreak of a very drug-resistant bacterial strain in 2016. “This is a really promising success story,” said Holm. “Unfortunately, the rollout of typhoid vaccines is still limited.”

The IVI is working on improving access to existing vaccines while at the same time developing new ones, including against tuberculosis, gonococcal disease and other intestinal infections.

At the Institut Pasteur Korea, researchers are also investigating bacterial physiology and resistance mechanisms to identify new molecules in bacteria and the drugs that can be used to target them. The institute has eight ongoing projects targeting various gram positive and negative bacteria, and they are working with local and international partners to develop new therapeutic agents against antimicrobial-resistant bacteria.

Did you know?

Conjugate vaccines incorporate two components linked together in order to trigger a stronger immune response against a microbe.

Establishing clear targets in national action plans

Thailand has exceeded its goal of reducing antimicrobial consumption in animals by 30%.

At the country level, Thailand has been especially successful in developing and implementing their National Strategic Plan against AMR. Before the plan, the country’s ministries were not working together to combat AMR, explained Nithima Sumpradit, from Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health. But since the plan’s implementation in 2017, the health, agriculture and environment ministries have jointly developed an integrated AMR surveillance system using the One Health approach. Further, many antibiotics have been classified as prescription drugs and work is on-going to reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in outpatient practices for treating upper respiratory infections, acute diarrhoea and wounds. Thailand has also prohibited the use of antibiotics as a growth promoter in animals and has regulated their use in feeds.

“Thailand set out very ambitious goals at the beginning, but we think that, as long as they are measurable, they can advance our action beyond expectation,” said Sumpradit.

Country ownership is critical for the success of action plans against AMR, added Satyajit Sarkar, a research scientist at the International Vaccine Institute. He emphasized the importance of using existing data at national, regional and global levels to inform the policy decisions that are needed to combat AMR.

Did you know?

Gram stains are used to classify some bacteria into gram-positive or -negative, according to the physical properties of their cell walls and depending on whether they pick up the stain.

In a world working to end the COVID-19 pandemic and prevent the emergence of new ones, “words should be supported by investments in interventions against AMR,” concluded Eduardo Banzon, principal health specialist at the Southeast Asia Department of the Asian Development Bank.

The world is at a tipping point. The painful lessons learned during the past two years must lead to joint global efforts towards developing actionable solutions to prevent some of the most challenging health and environmental crises that our species has ever faced.

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Antimicrobial Resistance

We welcome you to reproduce articles in Asia Research News 2022 provided appropriate credit is given to Asia Research News and the research institutions featured.